The tattoos on the chest of a prominent participant in last week’s Capitol invasion and riot are Norse symbols now used to indicate adherence to far-right politics, writes an expert in Old Norse mythology.

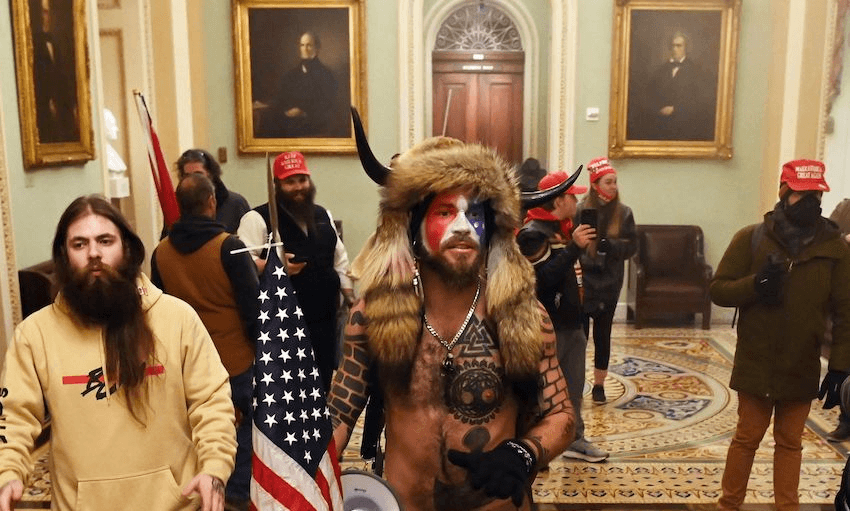

The defining image of the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 was undoubtedly that of a bare-chested man posing resplendent in a horned fur hat and face paint. Images of him in his weird costume have been shared across the globe – he seems to perfectly encapsulate the absurdity of the mob takeover of America’s sacred seat of power.

The individual in question has since been identified in the media as a far-right activist from Arizona by the name of Jacob Chansley (also known as Jake Angeli). He was quickly alleged to be an adherent of the QAnon conspiracy theory – though not before fake rumours spread that he was actually an antifa “plant”.

One thing that should make it very clear where Angeli’s politics lie are his tattoos. On his torso he has a large Thor’s hammer, known as Mjölnir, and what appears to be an image of the Norse world tree, Yggdrasill.

Mjölnir is one symbol we can be pretty sure was used by the original adherents of the Norse belief system, perhaps to summon the protection of the god Thor. Yggdrasill is the giant ash tree that supports the Norse cosmos, its branches reaching into sky realms inaccessible to humans, and its roots to the subterranean realm of the dead. Unlike Thor’s hammer, it was only rarely depicted by the Vikings, and representations such as the one below are modern interpretations.

Above these tattoos with a central place in Norse mythology is one that is more contentious. It depicts a valknut – an image that appears on two Viking-Age stones from Sweden carved with scenes from Norse mythology, including the Stora Hammars I stone on the island of Gotland.

The symbol’s original meaning is unclear, but it appears in close proximity to the father of the gods, Odin, on the stones. As Odin is closely connected with the gathering of fallen warriors to Valhalla, the valknut may be a symbol of death in battle.

Snorri Sturluson, a medieval Icelandic collector of myths, tells us in his “Language of Poetry” that a famous giant called Hrungnir had a stone heart “pointed with three corners”, and so the valknut is sometimes also called “Hrungnir’s Heart”. Whatever its original meaning, it has been used in more recent times by various neo-pagan groups – and increasingly by some white supremacists as a coded message of their belief in violent struggle.

Borrowed symbols

Angeli claims that he wears his bizarre costume to draw attention to himself – but there’s surely another reason for the bare chest and precariously low-slung pants. He is displaying these tattoos to full effect, and wants them to be seen.

Many people have similar tattoos which express their neo-pagan belief, Scandinavian heritage, or interest in the myths. But there is no doubt that these symbols have also been co-opted by a growing far-right movement. A hint at where Angeli lies on this continuum is in a tattoo that is less visible on his left shoulder, but which several academics including archaeologist Kevin Philbrook Smith have pointed out seems to be a version of the Sonnenrad, or sun-wheel.

This is a symbol listed by the Anti-Defamation League as “one of a number of ancient European symbols appropriated by the Nazis in their attempt to invent an idealised Aryan or Norse heritage”. Often it contains a swastika or other hate symbol – but worn with nothing inside, it is very easy for other white supremacists to fill in the blank.

Dog whistles

There is, of course, a long history of the co-opting of Norse imagery by the far right. Beloved of Himmler, the runic script inspired the insignia of the SS, while the swastika is another of those “ancient European symbols” that features in various forms on picture stones and runic inscriptions.

This misappropriation continued after the fall of the Third Reich, though in a more muted form. Neo-Nazis – at least those not brazen enough to wear a swastika – tend to opt for less recognisable symbols. These include numbers representing “Heil Hitler” (88 – H is the eighth letter of the alphabet) or “Aryan Brotherhood” (12 – letters one and two). Far-right adherents also favour other characters from the Germanic runic writing system which communicate similar messages.

One of these is the Othala runic letter – its name means “inherited land”, and so it frequently appears in the emblems of white nationalist groups from Ukraine to the US.

These “coded” symbols, and others newly borrowed from Norse myth, are even harder to spot and condemn. In the UK, Sky TV recently cancelled a reality TV show after viewers complained one contestant was covered in tattoos – including on his face – that could be seen as having far-right connotations. But if certain symbols are hard for the general public to spot, they are certainly dog whistles to members of an increasingly global white supremacist movement who know exactly what they mean.

Sky caught up in row as contestant on Lee Mack's new show has to deny he's got 'Nazi tattoos' on his face https://t.co/PFhidGAAgb

— Red Tory (@78SoylentGreen) October 20, 2020

Many scholars argue that the best way to counter far-right misuse is to drown it out with positive and accurate representations of Norse myth – the position I took in my recent retelling. But in the wake of the mass shooting in Norway in 2011 by Anders Breivik, who named his guns after weapons of the Norse gods, as well as the 2019 Christchurch mass shooter, with his allusions to Valhalla, and of this latest poster-boy of far-right insurrection, we have to think very hard about whether this is the right approach to counter a truly global extremist movement. At the very least, academics – and anyone else with a genuine interest in Norse mythology – need to be far more involved in countering these abuses of our subject on the ground.

Otherwise, we run the risk of ceding the field to those who see the vague concept of “Norse heritage” as a way to further unite an international fraternity of violent white supremacists.![]()

Tom Birkett, Lecturer in Old English, University College Cork

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.