Alex Casey visits the largest gemstone collection in the country, and meets the 85-year-old owner trying to Marie Kondo the lot.

Despite its charming name, someone once warned me that Birdlings Flat was like a place from the Twilight Zone. Hang a right off the winding roads to Akaroa and you’ll quickly find the spooky settlement that is home to 200-odd people, dozens of ramshackle baches, and at least one stray dog eating what really looked like a human lung. The Little Library had a faded copy of Marc Ellis’s Good Fullas, and a poster for a community production of Willy Wonka.

But in the words of the philosophical chocolatier himself: if you want to view paradise, simply look around and view it. For there is paradise to be found in Birdlings Flat, especially if you are prone to fossicking and treasure hunting. The expansive pebble beach is famous for its twinkling agates and uniquely coloured smooth stones. You know that feeling of delight in finding the perfect skimming stone? Every stone in Birdlings Flat is the perfect skimming stone.

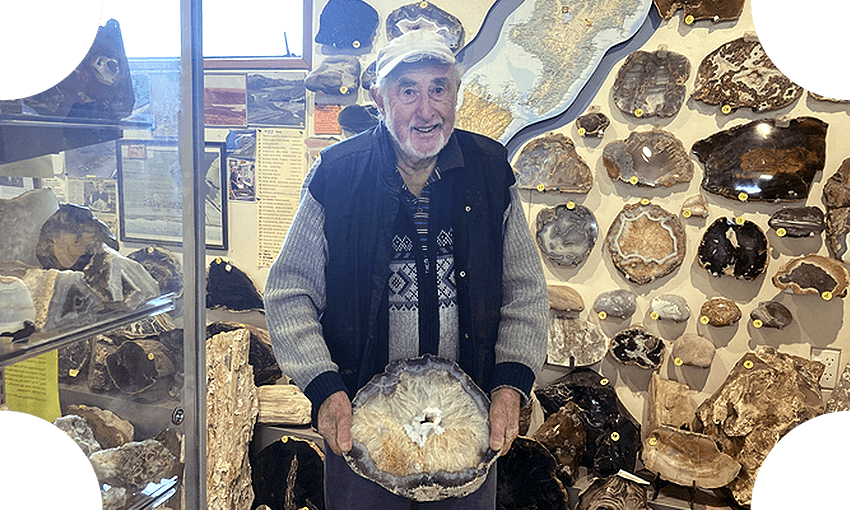

Nobody knows this better than Vince Burke, the 85-year-old proprietor of the Birdlings Flat Gemstone & Fossil Museum, and New Zealand’s largest collection of natural gemstones. Groaning with over 10,000 items, it is impossible to absorb the kaleidoscopic collection when you first enter. There’s rusty red jasperized wood from the Coromandel, millennial pink rhodonites from Dunedin, and cornflower blue agates found just 100 metres away on the beach.

I had been excited to see the collection in person, if not a little nervous about meeting Burke. The Google Reviews painted a perturbing portrait of the museum host, with some visitors describing a “very creepy” communication style. “Came outta no where, and just stood behind me for a good 30 seconds without me knowing,” wrote one. “Thought it was a spirit.” Others said Burke had a “sour attitude”, was “unfriendly and disinterested” and “kinda silent”.

But as he began shuffling around in his tatty pale blue cap, no doubt sunbleached from years of combing the beach, Burke was the opposite of “kinda silent” about his passion. “This will give you an idea how the currents work in New Zealand,” he said, picking up a snow white piece of quartzite. “This stone here is a West Coast stone from Hokitika,” he spun around to point out the window. “I picked this up over there on the beach, so that’s gone right around the South Island.”

Burke explained that the combination of ocean current and geography have made Birdlings Flat a unique vestige for all sorts of precious things to wash up. “Everything comes down the Rangitata River and ends up at Birdlings Flat. With the way the peninsula is shaped – basically nothing can get past us.” It’s why he still spends a lot of his time scouring the beach for fossilised wood and glowing agates, especially after a big swell from the south.

“That shifts all the fine shingle off the top and exposes this stuff,” he said. “Because the good stuff’s all about 500 millimetres down.” As for what “the good stuff” actually looks like: “you’re going to want to look out for lines, translucence and interesting colours. If you can look into it, then that’s a good one.” When conditions are right, he’ll still “whistle down” the beach for a look, but admits there’s always three or four others doing exactly the same in front of him.

For Burke, it’s all about the thrill of the chase. “I think that’s the beauty of it all – you just don’t know what you’ve got until you get home. Some just fall to pieces, and then other times this is what you get,” he said, pointing to a giant slice of agate that looked remarkably like a setting sun over the water. “That’s what makes it all worthwhile.”

This lifelong treasure hunt started as a young boy, when his family would take a break from life in 1960s St Albans to visit Birdlings Flat for the weekend. “Back then there were about three people who lived here, just in little huts and train carriages,” he said. He scored his first agates while fishing with his dad, and kept the hobby up throughout his adult life, scouring the country with like-minded gem hunters. He retired in the 2000s and opened the museum in 2007.

While the museum delivers on the gemstones and fossils promised in the name, it also contains many surprises. There’s a stuffed toad with a note that says “I bite” (“sent over from a cobber in Australia, he’s a bit of a joker”). There’s a scary blank-eyed doll in the corner wearing a ballgown entirely covered in seashells (“the person that owned it didn’t want it anymore”). Outside, there’s a DVD box set of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Broadway favourites for sale for $8.

Most curious of all are the things Burke has found on the beach that aren’t of the natural world at all. Remote controls, primitive early-2000s cellphones, golf balls, sunglasses, rugby balls, hairbrushes and even a g-string sit alongside 65-million-year-old volcanic rock. The door to a birdhouse with the warning “adults only” revealed a withered plastic penis. Dildo? Decoration? “Found on beach in 2003,” the sign read. “Did not find the rest of body.”

There’s also plenty of valuable items. “Our best find from around the Horata River was this one here,” he says, pointing to a large petrified log. “A lot of them have been fractured and had big chunks taken off, but this is one of the best ones I’ve ever seen.” He once had a woman visit and offer to write him a cheque for $10,000 for the piece of wood on the spot. “I just said: ‘no you won’t’. I didn’t want to sell it to her, I wanted to keep the collection together.”

But Burke has now found himself in between a rock and a hard place when it comes to his life’s work. “I’m getting on a bit,” he said. “My children aren’t interested, and they don’t really appreciate the value of the collection. I’d sooner sell it and give them some money, rather than a pile of rocks that they won’t know what to do with.” On the bright yellow COLLECTION FOR SALE sign, the $750,000 asking price has been changed with a Sharpie, reduced to $650,000.

Has he had much interest from buyers? “Not really,” he said. “People are blown away by it because it is the only collection of New Zealand material that’s open to the public like this. So I get a lot of questions about it, but that is always about as far as it goes.” He’s given himself two more years to sell the collection in its entirety, before he’ll sell off and donate the more valuable pieces one by one. “But at the moment, I’m in no hurry.”

And just because he’s looking to sell, doesn’t mean his collection has stopped growing. His tumbling machines were whirring out the back as he told me about his white whale – a 100kg agate on a private property somewhere near Mount Barossa. He has permission to extract it, and has found an old trawl net to haul it down the hill, but needs to wait until summer. “That’s the big one,” he said, pointing to a framed photograph of it in situ. All I could see was a rock.

After leaving Burke’s rainbow collection for the grey drizzly day, I headed over to the beach to see if I could find myself a precious gem. There was nobody on the entire stretch of pebbles apart from a small group of scientists, who told me they were hoping to get some data about eel migration, but their equipment wasn’t working. I plodded along the beach, head down, gasping every 30 seconds at a new tantalising bit of glimmering treasure.

When I made it back to Christchurch, Burke’s words ran through my head: you never know what you’ve got until you get home. I emptied the contents of my tote bag onto the kitchen table and left them in the sun to dry, much to my husband’s delight. But when I returned the shine had dulled, the translucence gone, a boring grey replacing what I had sworn were scorching hot pinks and acidic slime greens hours earlier. At least they’ll make good skimming stones.