What we wear to work says a lot about our jobs, our culture, and ourselves. What do the origins of professional dress tell us about its future?

For most of us, paid employment takes up a significant part of our lives. What we wear to work says a lot: how we conceive of work itself, what occupational hazards might result from the job we do and cultural conceptions of respectability, to name a few. But in the digital era, hot off the heels of the pandemic, our relationship to work is changing. How does our workwear reflect this evolving relationship, and what is the future of professional dress?

One of the original symbols of workwear was authority. In European history, court liveries – special clothes worn by the servants of wealthy families – were the first uniforms. Through colour, insignia, cut and decoration, they would illustrate a houses’ authority and wealth. Armies were the next to adopt uniforms, with appearance varying to denote rank.

In the modern era, some mandatory uniforms originate in response to occupational hazards, like firefighter’s suits. But uniforms are still used predominantly for those in a service or state industry, and they’re still markers of authority: authority to access your property (eg to deliver mail, collect rates or respond to an emergency); authority to handle financial transactions; authority to fly a plane, and so on.

But workwear has evolved beyond uniforms. With the rise of the office class in the 50s came the birth of the “business” dress code. Many items considered appropriate for professional spaces originate in formal, traditional European dress, the suit being the most iconic example. Colonialism in the previous centuries meant that Western clothing was considered a sign of progress and civilization, and adopted in colonised countries. These values found their way into our modern perceptions of business wear.

Dress codes have often been used to oppress minorities and enforce the dominant cultural standards. In recent years, school dress codes have consistently made headlines for reinforcing racism and sexism, but that’s true in the professional world as well. Through the feminist, civil rights, and LGBTQ+ movements of recent decades, a growing cultural awareness of diversity has meant a pushback against certain dress codes and a reexamination of what’s considered professional, or not. Rules around visible tattoos and piercings have relaxed, for example.

Since the 90s, corporate dress codes have been relaxing, and there’s also a trend towards diversity and inclusion: some workplaces like Kiwibank are adopting more customisable uniforms which include options that reflect gender and religious diversity, as well as encouraging staff to wear cultural markers. “Outside of a uniform where there may be an occupational health and safety standard, individuality is being embraced rather than having to fit a certain mould,” says Dress for Success volunteer Kim.

The past few decades have seen massive social change and disruption. The advent of the internet led to mass social movements and organisation on a new scale, and a pandemic forced a re-evaluation of almost every aspect of life. So it makes sense that in recent years our relationship to work, and therefore workwear, has also been shaken up.

The pandemic caused massive changes to our work culture, normalising remote work and creating demand for a more flexible working culture. It’s no wonder then, that workwear is reflecting these new conceptions of work, with less of a need to reinforce a sense of authority through dress and a preference for casual attire, especially for those who work from home. “I think businesses are beginning to realise, particularly if you’re in a back-office sort of job, what does it matter what you wear?” says Andrea Hardy, who also works with Dress for Success and has extensive experience in the HR world.

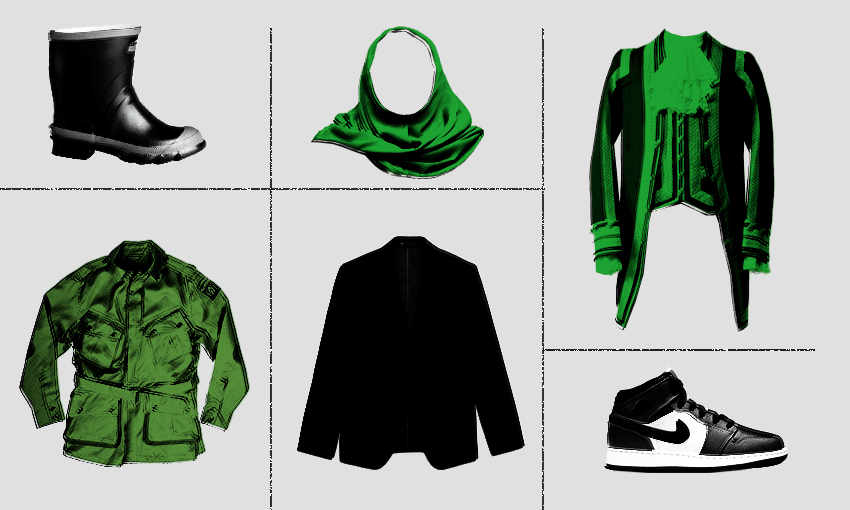

Increasingly, even leaders are pushing the boundaries of workwear and questioning formality. Rawiri Waititi made headlines for wearing his Nike Air Jordans in the house of Parliament, and Jacinda Ardern donned a hijab to show solidarity with Christchurch’s Muslim community.

So what is the future of workwear, given all this? I have the depressing hunch that work and life will become increasingly synonymous, because we’ll always working in some form, whether that’s our formal job, side hustle, or the monetisation of our hobbies. A lot of that work will be online, so Kirsten Smedley, Auckland Central manager for Dress for Success, predicts a trend toward wearable technology.

The future of workwear might also be considerably more practical. As climate change worsens and people become increasingly environmentally conscious, Smedley points towards practical solutions to commuting and unexpected weather events. Perhaps one day the gumboot might be acceptable office footwear. Smedley also doesn’t think the trend toward more casual attire is going away.

It’s difficult to predict exactly how our cultural perception of work, and therefore our dress codes, will change in the future. But one thing’s for sure: workwear will continue to reflect the zeitgeist.