It is clear that emissions reduction must be the priority in the face of the climate crisis. But some argue that we should also be more actively exploring techniques to alter the earth’s natural systems at same time.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) climate report made one thing really clear: we need to quit putting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. But maybe more than that we need to get the stuff that’s up there already out. Geoengineering, some believe, may be one way to do both.

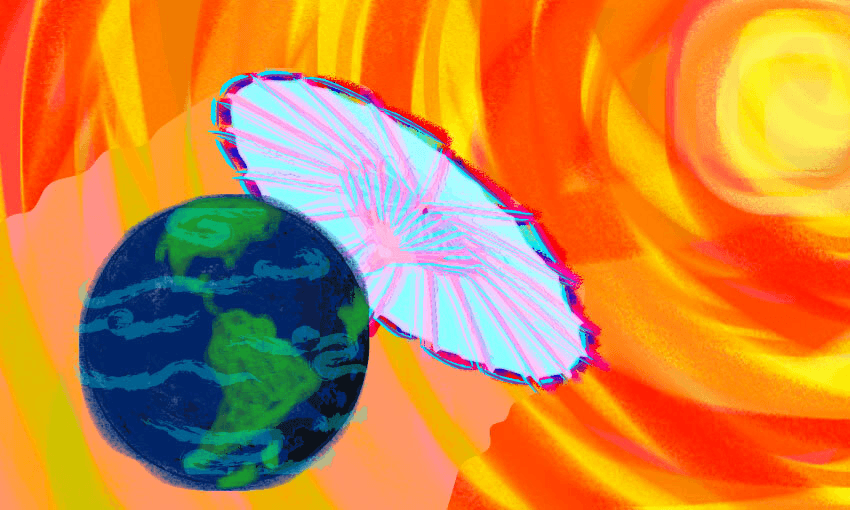

The word geoengineering broadly refers to techniques that try to alter earth’s natural systems to ease the impacts of climate change. On the less radical end it could mean adding machines to power plants to trap carbon before it leaks into the atmosphere. On the sci-fi end it could mean launching mirrors into space or particles into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight away from earth, and prevent further warming.

It was all the rage at the time of the last IPCC report, around 2011 to 2014. The IPCC held their own expert meeting about the future of the tech and here in New Zealand, our Royal Society, Te Apārangi, held a workshop to talk about potential options.

Geoengineering seemed plausible and really useful but there was an air of trepidation. Since those boom years, things have gone a bit quiet, especially on the home front.

So what happened?

The main argument against geoengineering is that it creates a moral hazard – that if a country finds a way to prevent the negative effects of climate change without reducing emissions, we’ll all just stop trying to reduce them. Or, that even thinking about geoengineering diverts attention and financial resources away from the urgent issue of emission reduction.

That argument seems to have won out. Some researchers, like Philip Boyd, a professor of marine biogeochemistry at the University of Tasmania, say the moral hazard argument is seriously hampering research efforts.

Research projects on geoengineering have been funded and then abandoned, early studies haven’t been published in academic journals, and websites detailing research proposals now display 404 error codes, noted Boyd in a 2019 article in Nature .

Speaking to The Spinoff now, he argues that the world can no longer choose between mitigation and geoengineering. “We don’t actually have the luxury of a fork in the road now. We have to do both. The IPCC report makes it very clear that we need the pull and the push. We need emissions reduction but we also have to remove some of the carbon now.”

It’s not an approach that should be taken lightly, he says, but should be investigated. “It is essential that investigations are solidly researched, openly discussed and made readily available,” he wrote in 2019.

We can’t get to the point where we need geoengineering and don’t have it available, echoes Greg Bodeker, owner and director of New Zealand sustainability research company Bodeker Scientific. There might come a scenario where climate change becomes runaway, and we need an emergency stop button.

He does however express concern about who would govern the tech and who gets to decide when to switch it on and off.

Researchers should focus on understanding the real potential consequences of the technology, Bodeker says. That’s another reason progress on geoengineering has stalled: scientists don’t yet fully understand what could happen to the climate or the environment in general if the world hit “go” on it.

One 2018 study found that forms of geoengineering present “large risks” for wildlife, forests and water resources.

Boyd notes too that many questions about ocean geoengineering remain unanswered. For example, it might be possible to hack the oceans to either reflect more sunlight, by spraying a reflective foam on top, or absorb more CO2, by helping it grow light-eating phytoplankton or dissolving a chalk-like powder in it. But will those powders enter the food web like microplastics have? Will the foams last too long? Or spread to areas we don’t want them to with the wind?

Some of those questions could be addressed through computer modelling or simple lab experiments. And New Zealanders could be the ones to help answer those questions, according to Bodeker. He doesn’t think the country should be pursuing trials, since it’s so unlikely to ever deploy any of the techniques. “It would be like New Zealand suddenly deciding to build 10 nuclear power plants,” he says. His attempts to get funding for such a project, he says, have been rejected.

The other potential stalling point is feasibility. One geoengineering technique Bodeker thinks is promising is injecting millions of tiny droplets of sulphur into the stratosphere to reflect heat back out into space. He says that tech is about 90% there. But the true potential of geoengineering is unknown, argues Boyd, reiterating again the blockades in place. “If we can’t scientifically assess any marine methods then we can’t get a handle on their feasibility at very large scales.”

Other methods, particularly a subset called carbon capture and storage, have more of a track record of feasibility. Canada for example already has machines that trap CO2 at the place it’s created, like at coal-fired power plants, and then pump it deep underground where it can’t leach into the atmosphere.

There have been arguments made that carbon capture is just a ploy by Big Oil to keep fossil fuels around for longer. But the majority of scientists working on geoengineering see it as a supplement to cutting emissions, not a replacement, and a vast number of projects are funded by governments or have policies specifically against taking money from groups with ties to fossil fuels.

New Zealand briefly looked into carbon capture too, with the Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment (MBIE) publishing a report in 2011 identifying six plants that could be good carbon capture candidates.

But MBIE’s website now says carbon capture and storage has “limited potential” and an MBIE spokesperson told The Spinoff the government isn’t actively pursuing it.

It just isn’t worth it economically. New Zealand gets much of its power from renewables that don’t make much carbon and, according to the 2011 report, the cost to retrofit and then run carbon capture plants would be too high. That is, unless the price that it costs certain businesses to emit carbon goes up.

But it’s also possible to scrub the atmosphere of carbon directly, separating CO2 from the other gases in the air and then storing or using it. The US Department of Energy recently announced $24 million in funding for developing this kind of tech. That’s something GNS Science would seek funding to explore, if the New Zealand government gave the green light, alongside their other clean energy projects.

“GNS Science is in the process of looking at what research needs to be done to support this. This work is in the early stages,” John Burnell, Energy Futures Research Leader at GNS Science, told The Spinoff. He added that work in that area is currently in a lull.

Says Boyd: “The bottom line is that things really haven’t progressed far at all.” Boyd, who’s also part of a think tank whose objectives include finding ways to capture carbon, says the world needs one really good example to get them going.

“They need a project, they need to get the first cab off the rank. It might not sequester that much carbon but if it changes the public perception it can change the debate. People might say ‘we want more of this’.”

The government is currently considering the Climate Change Commission’s advice on emissions budgets and policy direction. They will release the first emission budget by 31 December this year.