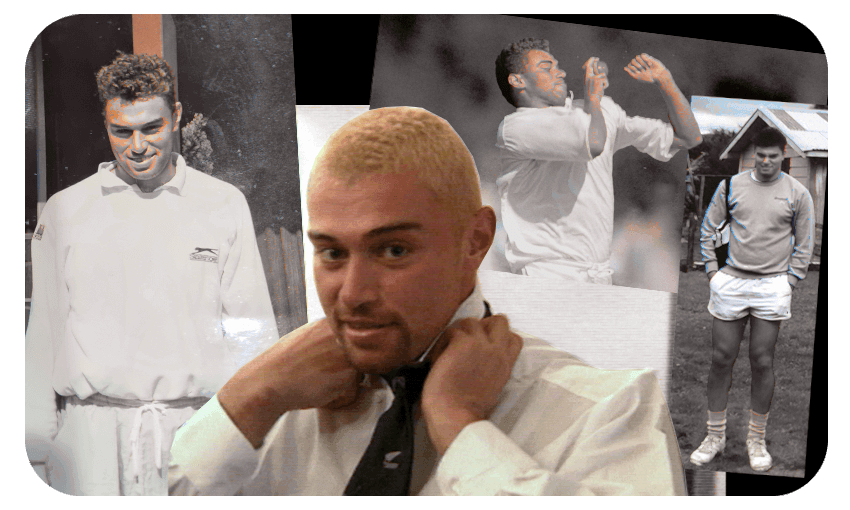

As a Central Districts age-group cricket rep, Dylan Cleaver witnessed a cricketing legend being written in real time.

What I’m about to tell you is mostly true: when Heath Te-Ihi-O-Te-Rangi Davis was 14 years old he was eight foot tall, had nostrils that flared like a Gorgon’s and could bowl at 150km/h.

If you don’t believe me it’s because you weren’t there cowering under the shade trees of Whanganui’s Victoria Park waiting for your turn to walk the green mile to the middle and face his peculiar brand of chin music.

Heath Davis. The name alone conjures up vivid, visceral memories. He haunted my teenage years.

I had the good fortune to be selected for age-group rep teams that regularly played his Hutt Valley and Wellington sides. And I had the misfortune of being nowhere near good enough to deal with him.

When you get to our age you think you remember more than you do about those snatches of youth. The broad outlines might remain intact but the colouring-in changes to suit the story you’re telling. But I remember every game my teams played against Heath Davis – the outlines and the colouring-in. Even if he remains a somewhat mythical figure, those matches were very real.

The first was a winner-takes-all game between Western Districts and Hutt Valley for the North Island under-15 title. This in itself was a minor miracle. We were two of the historically weaker teams, but that year we were coached by a technical genius named Phil Cooper (who had all the charm of an eftpos machine), and captained by the hyper-competitive, flame-haired allrounder David Lamason. Hutt Valley were usually the worst, but with Heath they had a puncher’s chance.

Auckland usually won these tourneys, with their brand new Gunn and Moore gear and parents who turned up in European cars, but although they boasted future Black Caps in Adam Parore and Blair Pocock, and possibly Mark Richardson too, they were savaged by Davis who reduced some to quivering, crying wrecks. I was watching on an adjacent pitch, spellbound by the carnage and staggered by how far back Hutt’s yappy wicketkeeper, future All Black Simon Mannix, was standing.

When the final day dawned it was unbeaten us (our game against Auckland was rained off, though we were on top), against undefeated them.

Cooper roused us early to go down to the nets. He had Wingnut Carroll, a Hawke Cup opening bowler and legendary local character, come in and bounce the crap out of the batters to prepare us for Heath. I knew I wasn’t going to feature in the playing XI when I didn’t get asked to face up to Wingnut, and to be honest I was relaxed about that – I’d had a lousy tournament, a run of bad form I never really broke.

We won easily. We were lucky. It was the last day of a full-on week of cricket and Heath was spent, though legend has it that he perked up enough at the prizegiving to do some strange interpretative stuff with sausage rolls, or maybe it was the chipolatas – my memory is a bit fuzzy on that one.

On and off-field stories about Heath became a cottage industry of their own. Everyone has a favourite. Like the time he bounced a kid called Rick McIntyre in an under-16 game and it cleared everyone for six wides. It was a short boundary, but even so!

Or the time a year later when David Lamason bowled so many bouncers at him that Heath came off at the innings break and wrote his name on his forehead in zinc. That’s what it was meant to be, except he ran out of room for a single-deck headline so it was instead:

LAMA

SON

… Only he’d done it while looking in a mirror, so he actually took to the field with:

AMAL

NOS

painted on his forehead.

By the time he got to under-20 level, Davis was still big and scarily fast, but we’d all grown up too. At Central Districts we had our own bully in Johnny Furlong. On a lively wicket with good pace – again, in Whanganui – we skittled Wellington for under 200 in the first innings, then found ourselves 17-5 before scraping a small lead.

I faced one ball from Heath that day and it smashed into my ribs via my glove. It ballooned in the direction of fine leg and I scurried to the other end to check for broken bones. I wasn’t sure what was the graver injustice: the single being given as leg byes, or the atrocious LBW decision I got a couple of balls later.

By the time the second innings rolled around the pitch had flattened out nicely, and for the first and only time I managed to dig in long enough to see the full range of antics he was becoming famous for.

Heath would chide himself in between deliveries, constantly berating himself in an incongruously soprano voice. He’d flap his arms around, whinny like a horse (at least I think that’s what he was doing), bowl a steady stream of no-balls and, just when you thought he was done, rip one over your shoulder from around the wicket to remind you he retained lethal power. I had the best seat in the house – especially, it should be said, at the non-striker’s end.

Some of us that played that game have remained in touch.

Even back then we all knew Heath was “different” – a catch-all term used by young males to describe any other young male whose life didn’t revolve around the twin pursuits of getting steamed and pulling chicks. It would be wrong to say cricket was an enlightened environment, but (apart from Canterbury, perhaps, where the conservative streak ran strong) being different was tolerated if not necessarily celebrated.

I asked some of my former teammates for memories or anecdotes about Heath.

Our keeper, Glenn, ended up playing club cricket with him in Wellington, and remembered days when he would bowl until his feet bled. Tarz, who ended up playing some first-class cricket with Heath, said “he was a real good dude and when you sat down and talked cricket with him he knew his stuff, but it was clear he didn’t have a whole lot of love for or trust in the New Zealand set-up of that era”.

“I watched him bowl one spell in a first-class game and couldn’t believe it. Real pace. I was 12th man, so was very relaxed.”

Then, of course, there’s the story about playing while tripping on acid, a hyper-niche category of sports history that has already been the subject of a brilliant baseball documentary.

I played a tiny, unmemorable part in Heath’s back story; the role he played in mine was much bigger. For me he really was, if you scroll right up to the top, a larger than life character.

I hope he reads this if only to realise there’s a bunch of us that still talk about him and remember him fondly. We might have played against better cricketers – though don’t get me wrong, Heath was a hell of a bowler – but few that have left such an impression.

When Heath Davis was 22 yards away, about to unleash another ball in your general direction, for a split-second you truly knew what it meant to feel alive.