After a short but successful career in China, table tennis champion Chunli Li moved to New Zealand to coach. She soon discovered she was better than everyone, and that was a problem.

Chunli Li trains alone. In the basement of the Panmure YMCA, four regulation table tennis tables occupy the floor space. On the wall is a linoleum sign printed in English and Cantonese: Chunli’s Table Tennis Club. Every morning and afternoon, Li trains dozens of school kids, teaching them the basics of table tennis. Occasionally she holds private sessions for advanced players or advanced players (women who have retired from work and have taken up the sport as a way to keep up with friends). Li coaches these players – some hoping for future success, others simply trying to stay active – and when they all go home, she trains alone.

Born in Guiping, in 1962, Li travelled the well-trodden path of Chinese table tennis players. An aptitude for the sport, or at least a natural hand-eye coordination, spotted by talent scouts at a school tournament, aged nine. Sent to Nanjing to attend a specialist school where students trained every day, morning and afternoon, and attended classes in between training sessions, not the other way around. At 15, Li began training in Beijing. By 20, she’d won a national team title with her province, marking Li as one of the top players in China. But being ‘one of the top’ in a country where over 70 million people play the sport competitively isn’t enough. Perfection is the standard.

When Li and the Chinese junior team came to New Zealand to play exhibition matches in 1982, the pressure was high. “When you represent the China team, you can’t lose a game overseas,” Li said, speaking from her club in Panmure. Luckily for Li and her team, New Zealand offered little in the way of competition. “We find out they’re not too difficult during that time. Because in New Zealand they don’t have a professional team…quite easy to beat them.” Li laughs, almost amazed at how much better she was.

But once she left New Zealand, Li lost a match. Representing China at the Asia Championships, Li lost to a Korean player. She was knocked out of the tournament and knocked out of contention for the World Championships. In a sport with such a high turnover as table tennis in China, that one loss was the beginning of the end. At 23, Li retired from the Chinese national team.

When Li visited New Zealand in 1982, she’d met with New Zealand Chinese communities around the country. So when the Manawatū Chinese Association contacted her in 1987 about a potential coaching position, Li didn’t hesitate. She remembered New Zealand being welcoming and more relaxed than her hometown. It would be a nice place to retire from playing and become a coach.

To nobody’s surprise, Li arrived and immediately beat everyone in the country. At her first national tournament, she won every game easily and collected her first New Zealand title. For the next nine years, Li won every match at every national tournament, winning nine titles in a row. She stopped playing in 1994 because she got an offer to play professional table tennis in Japan. Wasting everyone in New Zealand was fun, but it didn’t pay anything, and it wasn’t helping her game.

The Japanese professional leagues brought together the top players in the world, including Olympic champions. Li entered the men’s league. She wanted to win but more importantly she wanted to improve her game so “when I [play] against the ladies, I think I feel my power is much better.”

In all our interviews and time spent together, Li never once alluded to a natural talent. In fact, her focus in regards to her success was entirely on her work ethic. She remembers being selected at age seven not because she was a prodigy, but because the scouts saw she “look great and learn faster.”

When she joined the specialist table tennis schools, she knew she was still simply one of many good players. So she went one step further. “I’m training myself. I train very harder so I improve quite faster. After training one year, I can represent the team to play the competition.”

By the time Li got to New Zealand, her propensity to train herself would become essential to her athletic survival. New Zealanders simply didn’t train like professionals. As Li laughingly observed, “after the game they like to drink beer.” It may have been fun for her team mates, but someone with Li’s constant drive to improve would have a hard time finding training partners. And in table tennis, more so than other sports, training partners are integral to success.

Running out of ways to train on her own, Li invited her younger sister Karen to New Zealand in 1994. Karen was 15 years her junior, and a promising young talent. When she arrived, Li had just won her last national title. They trained together daily in their own two-woman squad, before Li departed for Japan. Karen continued to play locally and took over the family business of dominating New Zealand table tennis. In the end, Chunli won nine New Zealand titles and Karen won seven.

The sisters competed together as doubles partners, but in becoming team mates on the same side of the table, they each lost their only training partner. In order to train at the intensity required of Commonwealth and Olympic preparation, the sisters returned home to China and to their old province. Their two-week training camps in China would be the bulk of their preparation for these competitions.

The Li sisters loved representing New Zealand but if they were to perform at the levels they knew they were capable of, they had to leave New Zealand to train. It wasn’t that New Zealanders didn’t have the ability, it was simply the training ethic. When Li was 50 years old she came out of retirement to win the Oceania Championships. She was able to train in the lead up thanks to a Japanese player who was in New Zealand studying at the time. He went to Li’s club, recognised her from her time in the Japanese leagues, and asked if he could train with her. “We’re training together for about half a year. This is very helpful for me to recover.”

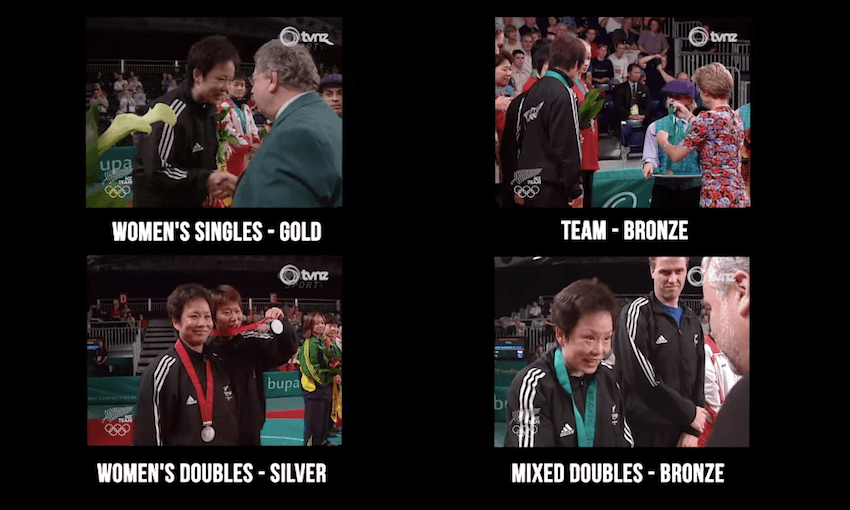

Li represented New Zealand at four Olympic games. On three occasions she was knocked out in the early rounds by the eventual medal winners. At the 2002 Manchester Commonwealth Games, Li won a record four medals (singles gold, doubles silver with Karen, mixed doubles bronze, and team bronze). She was 40 years old.

In 2008, Karen moved to Australia for work and family, and Li lost her training partner. Since she was seven, Li’s whole life had been table tennis. Her age had nothing to do with her love and commitment to the game. “I don’t have time to do many other things and also I believe in life, the time is limited. I just choose something I like so I always doing table tennis because I like table tennis.”

At 57, Li still likes table tennis and still wants to compete. She dreams of qualifying for the Tokyo Olympics next year, and knows she has to win a lot of matches to get there. She’s entered to play mixed doubles at the nationals this week, and will compete in qualifying tournaments later in the year. But she still has no one to train with. So after her students leave at the end of the day and she’s collected the hundreds of balls scattered around the gym floor, Chunli Li trains alone.

Chunli Li features in episode four of Scratched, a new web series that finds and celebrates the lost sporting legends of Aotearoa. Watch her episode here, and catch up on the series here.