With the start of alert level three, Shortland Street announced it would be the first drama in the country to start shooting again in a Covid-19 world. Chris Schulz talks to the soap’s cast and crew to find out how they did it.

When actor Michael Galvin arrives at Shortland Street’s Auckland studio to begin his working day, he no longer enters the building through the front door.

Instead, he heads to the side of South Pacific Pictures’ head office in Henderson to a different entrance where he signs a Covid-19 registry, then squirts sanitiser into his hands. Galvin then walks down a vacant corridor to his dressing room without seeing, greeting, or hugging any of the 48 other cast and crew working on TVNZ 2’s prime time staple.

“The whole building has a one-way system so we pass each other less,” says Galvin, a Shortland Street veteran and only original cast member still appearing on the show. “It’s like walking into a church. There are all these things you can do wrong, all these rules you can break.”

He admits: “[All of] the quietness and calmness, it’s slightly eerie.”

Once inside his dressing room, no one from the show’s costume department hands him his clothes, and no one from make-up touches up his face and hair, the things that turn Galvin into Shortland Street’s most famous face: Dr Chris Warner.

These days, Galvin takes care of all that himself, slicking back his hair and applying his own blusher under guidance from a physically distanced make-up artist standing two metres away. “I give myself a powder and a pat on the back,” he says. “[For] some of the other actors, it’s far more demanding.”

Life under lockdown for Shortland Street is a far cry from how New Zealand’s longest-running TV show was operating just a few months ago. Usually, more than 100 people work on-site. Sets are rearranged constantly and are buzzing with cast and crew. Scenes are churned through at frenetic pace. On a normal day, Galvin says they work at a “cranking pace with everyone in each other’s faces”.

“Shooting Shortland Street is like a permanent state of chaos,” he says. “Everything is happening all of the time… it’s a very social place. Everyone’s squashed in together.” Normally, they’d rip through 28 minutes of material – more than a full episode – in a day.

But thanks to the worldwide pandemic caused by Covid-19, all of that has changed. To adhere to the strict physical distancing regulations enforced by the government’s level three lockdown rules, Shortland Street has slowed down. With just half the normal number of cast and crew on-site, just 16 minutes a day is being shot. As one of the only scripted television shows still shooting in New Zealand – possibly around the world – it’s been forced to pivot in other areas too.

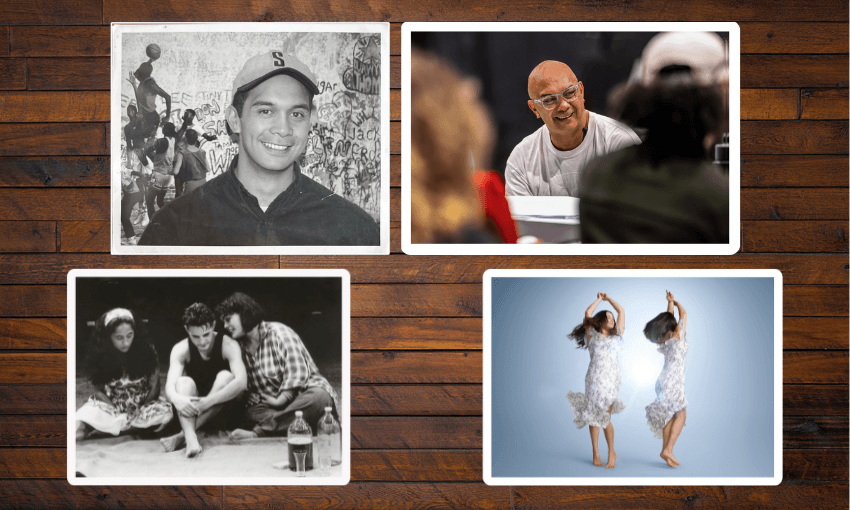

“It’s definitely odd… we’ve literally changed every aspect of how we shoot,” says Oliver Driver, who used to play Mike Galloway on the show and now works as one of the show’s two producers.

Scenes are discussed and rehearsed by actors standing at a two-metre radius, something that’s taken so seriously that last week’s director Ian Hughes carried a metre-long measuring stick with him at all times.

Props, including cellphones and iPads, are delivered by the art department in a plastic bag and is used by just a single actor before being returned for sanitising. Cleanliness is a massive priority. “There are hand sanitising stations everywhere,” says Driver. Overnight, a cleaning crew disinfects Shortland Street’s fake hospital to the standards of a real hospital.

With all gatherings banned under level three, the social scene has also taken a big blow. “We’ve removed the sociality of the job,” says Driver. “It’s like a ghost ship in here. Nobody’s hanging out and chatting. At lunchtimes, no one’s allowed to hang out in groups of more than three. You have to stay two metres away from each other.”

Some of these rules have been relaxed now that we’re in alert level two, but Driver says they’re taking their time to welcome back those who’ve been working from home. “We want to make sure the transition for cast and crew is slow and steady. Once they’re comfortable in level two, we’ll shift to level two… We’re super overly cautious because we want to make sure we don’t get anything wrong here.”

All those changes make life shooting a soap – with its high levels of invented drama and constant romantic upheaval – difficult for the actors. “The hard thing is when you have to comfort someone and you can’t actually put a hand on their arm or shoulder. That’s been the time when we’ve really noticed it,” says Galvin.

Kissing has been removed from scripts, directors are being creative with angles, and they’re using a telephoto lens in cameras to help create the impression of closeness.

“You get the illusion that people are close to each other,” he says. “Two people that are lying in bed, post-coital sort of thing, you can’t shoot a wide shot on that because they’re a metre apart. It just looks like they’ve had a horrific time together. If you keep that whole scene in close-ups, even though you never see the two of them in the same shot, it feels very intimate. It feels like first time lovers talking to each other.”

“It’s hard on the cast,” admits Driver. “Acting is a contact sport… You want to get in each other’s faces and grab that person as they’re walking away from you, you want to lean into the person you’re pretending to be in love with, you want to grab that baby.

“All of those instincts that actors have to show human emotion and human pain and human drama, none of that can happen.”

With all these changes, you have to ask whether Shortland Street had thought about doing the unthinkable and – for the first time in its 28-year history – taken a break.

“The concern for us was how long would level three last,” says Driver. “If we’d known it was two weeks, we would have waited, but we didn’t know it was two weeks. We knew we had to get back to work because unlike other dramas or shows that have seasons, we’re playing every night. [We didn’t] want to run out of episodes and [we didn’t] want to take this show off air because that’s never happened in our history.”

With the show down to airing three nights a week from its usual five, Driver isn’t sure when viewers will be able to see the changes, as the show works several months ahead. However, small mentions of the virus are beginning to make it into scripts. “The writers have done it very intelligently,” promises Galvin.

It might not sound like it, but there are upsides to Shortland Street’s behind-the-scenes drama.

Without realising it, the show’s been setting the standard for what life is going to be like for television sets in a post-Covid-19 world. Driver says Australian TV networks and other friends in the industry have been calling him for advice. “They’re fascinated by how we’re working,” he says.

Galvin also admits the slower pace suits him. “It’s actually quite nice to be doing one thing at a time. It means we don’t move quite as quickly, we don’t shoot quite as much, but from an acting point of view, it’s nice to have that time. It’s quite a luxury.”

Plus, there’s the obvious one: with unemployment rising, everyone involved with the show is feeling grateful for having a job to return to.

“I’ve been an actor and I’ve been a director and I’ve worked in theatre a lot, and my community is decimated by this,” says Driver.

“I’m watching Q Theatre try to get enough money to not shut the doors. Actors and directors… all their work disappeared overnight. I have friends who are choreographers who went from being fully booked for the year to having no work at all.

“We’re here, we’re working, we’ve kept everybody’s jobs and we’re all going ahead. You come into work and you go, ‘I can’t believe we’re doing this, I can’t believe we’re here.'”