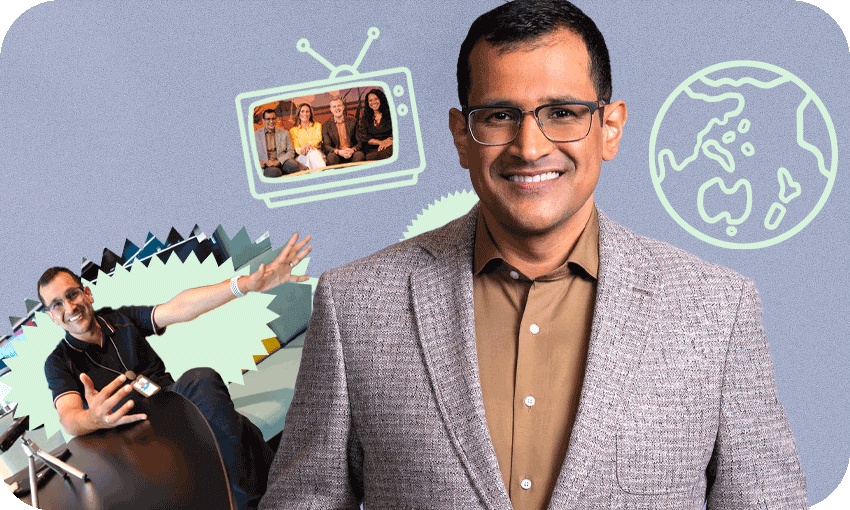

The new co-host of TVNZ 1’s Breakfast talks about returning home after more than 15 years at Al Jazeera, being ‘Mr Serious’, and the task of filling John Campbell’s shoes.

Kamahl Santamaria does a good John Campbell impression. “Helloo young man, how are yooouuu?” The scene is Flower Street, TV3’s Auckland headquarters, and a nervous Auckland kid called Kamahl, not yet 18 years old, is waiting outside news boss Mark Jennings’ office for a work experience interview. “I’m thinking: holy shit, John Campbell’s talking to me!” It’s 1998, and Campbell, recently thrust into the 6pm host’s seat alongside Carol Hirschfeld after what Santamaria calls “the Hawkesby fiasco”, pauses to chat and offers some advice. “Here’s what you’ve got to fucking do,” says Santamaria, embodying Campbell again, before disappointingly and sensibly taking the rest of the cheerful, slightly subversive and very expletive-ridden recitation off the record.

For Santamaria, who this week takes the Breakfast seat vacated by Campbell across town at TVNZ, those words “left such an impact”. He got the gig, and a year later he was reporting for the 6pm bulletin. “He was just so authentic. And such a journalist, you know, not just a broadcaster on air, such a good journalist. I watched and I learned.”

However polished the impression might be – he also does a good rendition of both Campbell and Anita McNaught turning sharply to the camera and introducing themselves in the intro to 20/20 – Santamaria says there will be no attempt at mimicry in the new role, but as the new guy alongside Indira Stewart, Jenny-May Clarkson and Matty McLean, he will try to emulate that authenticity. “That’s what John taught me all those years ago … just be yourself. That man is himself. The man you meet in the newsroom or in the studio or on the street is the same guy. I picked that up from him very, very early, when I was at 3, and I’ve always carried that through.”

We’re talking in the ground floor cafe at TVNZ’s central Auckland base. Thanks to omicron, it remains much less busy than normal, and we have the couches, and a big screen beaming out The Chase, to ourselves. It’s the Friday before his first week on camera, Santamaria has just come from a rehearsal and he’s in a buoyant mood. He repeatedly says he can’t wait to get started, almost as often as he bookends an answer with the caveat that he’s barely stepped off the plane and it’s all very new – “ask me again in three months”.

He’s keen to disabuse any characterisation as Mr Solemnity, despite coming off 16 years covering weighty issues at Al Jazeera English, the Doha-based international news channel. “I think I may surprise a few people who think, ‘oh, that’s the serious news guy’. That’s what I’m reading in some of the things which have been written by my former employers in New Zealand. You know, ‘Kamahl is a senior broadcaster’, he says, screwing up his face. “I mean I am very much a serious broadcaster. I take my job seriously. But I think they will be pleasantly surprised. I hope they will.”

Santamaria is alluding to recent comments by Jennings, but more with mischief than pique. Like many in New Zealand television, he credits Jennings for taking a chance on a raw young talent. His time at TV3, initially as a sports reporter, put him on a path that would lead around the world. After two-and-a-half years as a one-man Melbourne bureau for Sky News Australia he landed in London. His luck seemed to have run out, and CVs went unanswered, until recruiters for a yet-to-launch news channel, Al Jazeera English, invited him in for an interview. He was offered a position as a London-based producer. “I was thrilled with that. But then they said: how would you like to go to Doha and be a presenter?” He’d done presenting, but not as a news anchor, not for rolling coverage. “So they took quite a risk on me, in hindsight, as every boss I’ve had seems to have done, bless them. They needed people to go and they needed young, enthusiastic people who were going to go and throw themselves into this project in this faraway land.” He chewed it over with his partner, now wife, “and we sort of said, ‘We’ve got to try this. Because to sit in the newsroom in London and be watching a presenter in Doha and thinking I could have been doing that, you know – that would not sit comfortably. We’ll do it for a couple of years, we thought, like most people. And that turned into 16.”

Over the course of those 16 years, the first of which was before the channel went to air, Santamaria found himself surrounded in the desert city by a cluster of other New Zealanders; Anita McNaught, Elizabeth Puranam, Tania Page, Charlotte Bellis and dozens of others behind the scenes who became known as AJE’s “Kiwi mafia”.

Santamaria had left Aotearoa at the start of 2002, aged 21. “I thought I’d head off for a couple of years. And that was 21 years ago. Just never quite made it back until now.” That latest decision was made in 2020. For all its appeal and proximity to so many fascinating parts of the world, Qatar made for “a very strange existence”, with citizenship all but unattainable. “I’d been away a long time, and had started thinking, ‘OK, where’s the next move?’” Eventually Santamaria, his Scottish wife and his Qatar-born daughter put the pin in New Zealand. “And I was,” he says, pausing for a beat – “I think scared might almost be the word, about coming home, because I’d gone for so long. I’d been working for Al Jazeera, which is great. But you know, it doesn’t have the relevance here that it maybe did in other parts of the world. And I thought, well, no one really cares that I’ve been at Al Jazeera for 16 years. I’m going to have to sort of start again. And then you get the life-changing phone call.”

The call was from Paul Yurisich, who had in 2020 been appointed TVNZ head of news. Santamaria had worked with Yurisich at Al Jazeera but knew him from further back. “He was producing Nightline back in the day on TV3 when I started there … So we’ve known each other for a long time. And he said, ‘We’re relaunching Breakfast and I’ve got something you might be interested in.’ It was a no-brainer.”

Global to local

Breakfast on TVNZ 1 is a different beast to Al Jazeera both in tone and content, but Santamaria says that’s something he relishes – and the Auckland newsroom is no poor cousin of the Doha set-up. “You know, there’s been a lot of perception that I’ve come from a big international news thing, and we’re coming to TVNZ, which is, by comparison, and I’m using air quotes here, ‘local news’. But it’s not like that at all. It’s a big operation down there,” he says, redirecting the air quotes in the direction of the newsroom. “And there’s so much more accountability. When you broadcast on international news, yes, you have an audience of millions around the world. But you don’t see them. You get interactions on social media. But you don’t have an audience in front of you, or around you. You broadcast into the void almost and there’s not – accountability is not quite the right word, but you haven’t got that audience keeping its eye on you.”

Santamaria says he’ll embrace the unbuttoned approach demanded by Breakfast. His happiest years at Al Jazeera were fronting the magazine-style “interactive news bulletin” Newsgrid, which was “looser and more chatty”, he says. “The formality of international news kind of hemmed me in a little bit.”

As for subject matter, he’s racing to get up to speed on domestic detail. “I’m not as up with all the local issues as other local journalists will be. I say that quite openly because I can’t pretend otherwise.” And he’s enjoying it. “I’ve only been back two weeks, but you watch the six o’clock news, you read the local websites and newspapers. The things you are reading are far more relevant to you: inflation, price of petrol, these kinds of things, which seem very local stories, but they are very relevant to me now.”

Santamaria nevertheless hopes his familiarity with world news can be a boon on Breakfast. “I will always be an advocate for international news,” he says. “One thing I hope to do here is bring more relevancy to that, to a New Zealand audience. I think there is still this view that, oh, it’s international news, it’s a few stories half way through the six o’clock news.” There is a chance to foreground more than the huge stories such as Ukraine, he says. “If we make it relevant, if we explain that Gaza is being bombed and that is the equivalent of having the population of Auckland and Wellington combined in an area 40km long – then now it makes sense, now it may not be relevant to a person’s everyday life, but they can understand. That’s what I will push for as far as international news is concerned.”

I throw another example at him. Could we expect to see coverage of the bloody, appalling, still-escalating conflict in Yemen? He takes a long breath. “I suspect not,” he says, then checks his answer. “My initial thought was that it would take a big event to be the news hook. Can I make the issue of Yemen something relevant? I don’t know yet.” It is, after all, Breakfast television. “You’ve got to be really cognisant of that. Informing people but not terrifying or boring them, making it too heavy. I think there will still have to be a news peg.” He stares up for a moment. “But then sometimes you go, hang on, Yemen is the world’s biggest humanitarian crisis, and as you say it’s not getting reported. If that’s not a big story then what is?”

While presenting outwardly focused news in the English language afforded Santamaria a good deal of privacy in the emirate of Qatar, a New Zealand breakfast host can expect to get feedback on their journalism, diction and wardrobe decisions direct from viewers at the supermarket. “I’m quite aware that it’s going to be very different here, that this is a small place and that my picture might be on a billboard somewhere or something like that,” he says. “And it’s – you know, ask me in another month.”

One new reality that Santamaria insists he’s very ready for is the three-something-AM alarms. The roster at Al Jazeera meant you could be required to start at almost any hour, playing havoc with the body clock. “So, yes, early mornings sound awful, but if you are doing it every day and you get your body into that routine, it’s OK,” he says. “Also I am incredibly antisocial so I don’t go out much. I eat my dinner, I watch my telly, and I go to bed,” he laughs, half proud, half embarrassed. “And I’m quite fine with that. I’m a creature of habit, I’m a creature of routine. This will suit me perfectly,” he says, tilting his head to add: “But again, ask me in another month, I might be saying, ‘for God’s sake what have I done?’”

Al Jazeera and soft power

The English-language Al Jazeera has been widely accoladed since its 2006 launch for bringing nuance and depth to its coverage, and reaching into territories, in the Arab world especially, too often neglected by its western counterparts. It is not, however, without its critics. British columnist Nick Cohen called it “the world’s most subtle and effective propaganda channel”. When I wrote ahead of its launch on New Zealand Freeview in 2013, Anita McNaught, who reported for the channel from Turkey and the Middle East, told me: “It is clear to me that Al Jazeera English has a challenge now, in proving to a sceptical viewing public in the Middle East, that it isn’t politicised by the fact that Qatar pays the bills, and that it remains a reliable and neutral broadcaster in all territories.”

There was no doubt, Santamaria acknowledges, that the broadcaster had been created and continued as an exercise in soft power – to achieve influence through cultural rather than militaristic might. “Absolutely,” he says. “Soft power is what Qatar has been about for a long time, certainly as long as I lived there. When I moved there, there were was only a population of 800,000 people, 300,000 of which were Qataris themselves. No one had heard of the place. They just assumed you were talking about Dubai. And then over the years, it was like, OK, Qatar is involving itself in solving a political crisis in Lebanon, in Sudan. They back then would even have Israeli officials coming for conferences, UN conferences in Doha, which would be unheard of in many other places. Then it was: we’re opening up a number of international universities here. Sports events, obviously, the World Cup is a big part of that. Rather than chasing the tourism dollar, which the likes of Dubai have done, they’ve decided: let’s go a little more long term. And yes, Al Jazeera was a part of that, obviously.”

But Qatar (about the size of Northland) was not always an unremarkable toe poking into the Persian Gulf. When it became part of the news, when the spotlight shone on allegations of appalling treatment of migrant construction workers in the World Cup project, or on the blockade of Qatar by powerhouses including Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the UAE, the risk of interference by its royal owners became greater. Santamaria says he never saw that happen. “Maybe it was happening above my head? I don’t know.” Certainly, he says, it was nothing like the editorial control exerted in Russia, China or Turkey.

There was and is an important difference, too, between the original Al Jazeera Arabic and its English language sibling. They occupy different buildings and share little apart from some facilities and footage. “We were very separate entities, and that disappointed me sometimes,” says Santamaria. “I wish we could have been a bit more integrated.” He recently narrated documentaries on the 25th anniversary of the Arabic channel, surveying “how they built this channel in Qatar. It was bonkers for those days, what they were doing there – challenging state narratives on live television in the Arab world. It was more groundbreaking than I’d ever understood … They were absolutely trailblazers.” That channel is more often caught up in regional political conflict, having been accused of becoming a mouthpiece for the Muslim brotherhood and facing accusations that “Al Jazeera is being used”, says Santamaria.

Their presenters are a different level of influential, too. They are “absolute superstars”, he says, pointing to a Jordanian host who was second only in terms of social media followers to Queen Rania.

The Arab Spring was a formative, explosive time for both channels, with the Arabic broadcaster a locus of debate within the region and the English version a fountainhead for much of the rest of the world. Santamaria recalls it as a “thrilling, mind-blowing” time to be sharing the news.

“Tunisia. Egypt. Libya. Yemen. What the hell is happening? I remember the day I saw Al Jazeera’s live feed was streaming on the front page of YouTube, and thought, OK, they’re watching us now.”

A name that circles the world

Among the social media messages welcoming him back to New Zealand was one that declared Kamahl Santamaria to be the most musical name in broadcasting. I asked him for the story of his matinee-idol-worthy name and – well, better to let him tell it:

“Santamaria in my instance is Portuguese. My father’s family comes from Goa in India, where the Portuguese came and brought lots of names like De Souza, Perrera, Fernandez, De Costa, and Santamaria was one of them. The Catholic Portuguese influence. So that’s where the name comes from. Actually, you mention Yemen. My parents were born in Aden. That’s where my dad was born, and my mum’s family moved there when she was very young. So they identify with Aden a lot, during British rule. Then they got married eventually in London and they moved to New Zealand 50 years ago, and my sister and I were born here – so we’re from all over the place.”

“And Kamahl – this has always been amusing, because my mum wanted, in the knowledge that we’re growing up in New Zealand, where people aren’t, certainly back in the 80s, exposed to Indian culture very much, is there an Indian-sounding name which they’ll know? Yes: the singer Kamahl! His full name was long, so he shortened it and just made it Kamahl, and people in the 70s and 80s knew that name – he was born in Malaysia and huge in Australia, oh my God – so Mum went with that. And living in the Arab world these last 16 years, people have been like: your name, you’re spelling it wrong, because it’s got an H in it. It perplexed a lot of people.

“My wife’s from Scotland. My daughter’s born in Qatar and has lived there 13 years of her life. We’re from all over the shop. And if people remember the name, great.”

Nerves and shoes

Santamaria was nervous outside Mark Jennings’ office almost a quarter-century ago and he’s nervous now. Just as well, too, he says. “It means that it matters. If you’re nervous about something it means it’s important, you’re conscious of it all, and I am. But I’ll just go on there and be myself, and see what New Zealand thinks.”

After 16 years in a Doha studio, it would take a massive breaking story to budge the pulse. “I’d been doing the same job for a long time and was obviously fairly confident with how I did it, so the nerves had gone and the adrenaline had gone in many ways. And that’s also the nature of 24-hour news, you just keep rolling – you do four bulletins in a row, sometimes they might all be the same.” That was part of the attraction with the new role: knowing it “would push me again, it would force me to go outside of my comfort zone”.

He’s been put at ease, however, by his new colleagues. A few days after he landed in early April, they met after Breakfast for breakfast. “It was like a blind-date-slash-speed-dating kind of moment where I’m meeting everyone for the first time – we feel like we know each other but we don’t,” he recalls. “And there were lots of questions. And I was very open with them. I said, I’m conscious of what I’m stepping into here. You guys are a tight team. And John has clearly had a very strong influence on you as a team and on the production team and on the viewership and everything… His impact is undeniable. I said, I’m very conscious I’m stepping into that. Jenny-Mae said: you know, we know he’s moved on and we’re happy for him, and we’re ready to start the next chapter with you, and that made me feel so good. I already felt very welcome, but that allayed many fears from the start.”

He found a similar encouragement at home, while watching John Campbell’s emotional sign-off. “I said, ‘Oh wow, I’ve got some big shoes to fill.’ And my daughter very sweetly said, ‘Lucky you’ve got big feet, Daddy.’” Santamaria quickly adds: “Now, she could have been directly referencing the fact that I do have large feet. I don’t know. But it’s those little votes of confidence along the way – it’s helpful. I’ve been doing this a long time but you still have plenty of doubts.”