The Netflix smash hit uses children’s games to tell a gripping and bloody story about survival, writes Jihee Junn.

There’s something deeply unnerving about stories subverting childhood innocence into something sinister. Hollywood turned dolls like Chucky and Annabelle into bloodthirsty demons, games like hide-and-seek into matters of life and death, and sweet little girls in prim frilly dresses (think The Exorcist or Orphan) into stone cold killers.

While Squid Game, the hit Netflix drama series from South Korea, certainly doesn’t fit the horror genre bill, its premise combining schoolyard games with brutal murder is almost as eerily chilling. Created by Hwang Dong-hyuk, an accomplished director most notably behind the 2011 film Silenced, Squid Game revolves around a man called Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), a divorced gambling addict and highly incompetent father drowning in an ever increasing pool of loan shark debt.

One day, while waiting for the subway, a sharply dressed man in a suit (courtesy of a cameo appearance by Train to Busan’s Gong Yoo) approaches Gi-hun and offers him money if he can win in a game of ddakji – Korea’s origami version of pogs – in return for getting slapped in the face for every loss. When Gi-hun finally wins after several painful rounds, he’s offered the chance to play more games for cash. With little to lose, Gi-hun bites, and ends up in a room with 455 others in a competition to win a billion dollar prize. Unfortunately, the price for losing has ratcheted up too, with a slap in the face replaced with gruesome, unflinching death.

Like Gi-hun, his competitors are just as financially desperate. There’s Sae-byuk (played by model Jung Ho-yeon in her acting debut), a North Korean defector trying to pickpocket her way to a better life for her family; Ali (Anupam Tripathi), a Pakistani immigrant whose employer hasn’t paid him in months; and Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo), a once gifted childhood friend of Gi-hun’s now wanted by the police for financial fraud. As time goes on, friendships and strategic alliances start to form between contestants. But in a zero-sum game of survival that increasingly pits its dwindling numbers against each other, these relationships inevitably start to fray – with some emotionally devastating consequences.

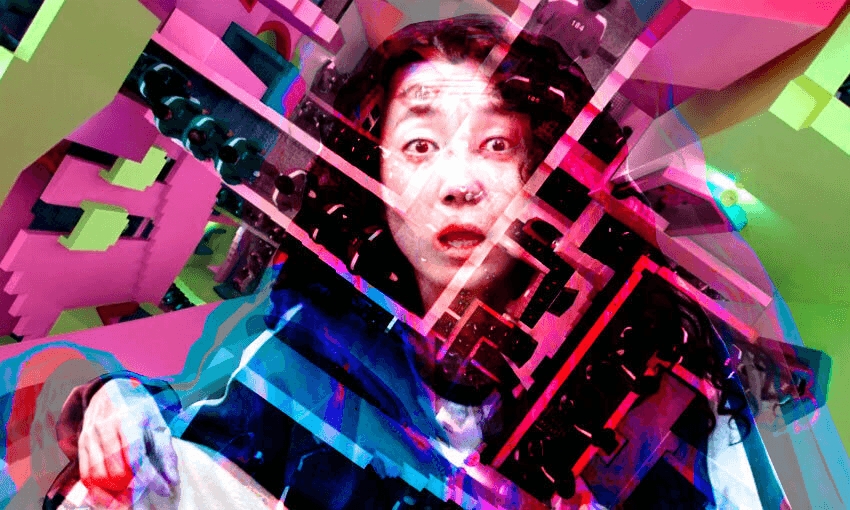

Visually, the world of Squid Game is a confection of forest greens, fuchsia pinks, and bubblegum pastels. Geometric shapes are a running theme, and the architecture reflects the mechanical structure of the games: a meticulously arranged control room, bunk beds stacked dizzyingly high, and stairways woven together like the works of M.C. Escher. Everything in this tightly controlled world feels artificial, and there’s something peculiarly unnerving about that. In the competition’s first game – a Korean version of Red Light, Green Light – contestants are ushered outside onto an empty field surrounded by walls painted to look like grass and sky (which, interestingly, reminds me of that final scene from The Truman Show) and a freakishly large animatronic girl at the other end. Things seem pleasant enough until the killing spree kicks off: the robot girl, equipped with a motion detecting sensor, starts gunning down contestants like a merciless drone.

There’s a macabre absurdity to watching grown men and women feverishly playing games designed for children. But the magic of Squid Game is that it’s more than just its intriguing concept – it’s a compelling exploration of societal failures and moral quandaries, as faced by a set of deeply flawed yet intriguing individuals. Hwang, Squid Game’s writer-director, recently explained he wanted to use these games for their simplicity, allowing viewers to “focus on the characters, rather than being distracted by trying to interpret the rules”. It’s a choice that’s worked: the characters serve as the driving force behind the story, revealing their true selves as the game goes on. And while there are a few characters whose motives, frustratingly, go unexplained, with potential for a second season as suggested by the show’s mysterious ending and its number one position on global charts – the first for a Korean series on Netflix – it’s highly likely there’ll be more to come.

While watching Squid Game, I was reminded of a film called The Platform – a Spanish dystopian horror where prisoners are kept in a giant tower and fed from the top-down. Both portray humans scrambling to survive in a dog-eat-dog world (in The Platform’s case, quite literally) and both touch on concepts and themes we’ve already seen in films like The Hunger Games, Battle Royale and, controversially, As the Gods Will – a 2014 Japanese horror film that sees high school students forced to play childhood games with deadly stakes (Hwang has denied accusations of plagiarism, stating he started writing the script in 2009). So while it doesn’t add anything hugely new to the fight-to-the-death genre, Squid Game’s pointed social commentary rooted firmly in modern life manages to lend the series a fascinating point of difference. There’s a universality in the show’s portrayal of the desperate poor and the grossly rich, but also a specificity that stems from the hyper-competitive, overworked and overstressed realities of life in Seoul (which, unsurprisingly, has led to comparisons with another South Korean mega screen success).

Unlike many of its cinematic predecessors, which depict people waking up in a dystopian nightmare with no choice but to kill or be killed, in Squid Game the contestants are all there, technically, by choice – and that gives it an extra layer of grimness. During a vote to either stay or leave the game, one of the contestants, Mi-nyeo, puts it poignantly: “So what if we leave? Tell me what changes? It’s just as bad out there as it is in here, goddamn it.”