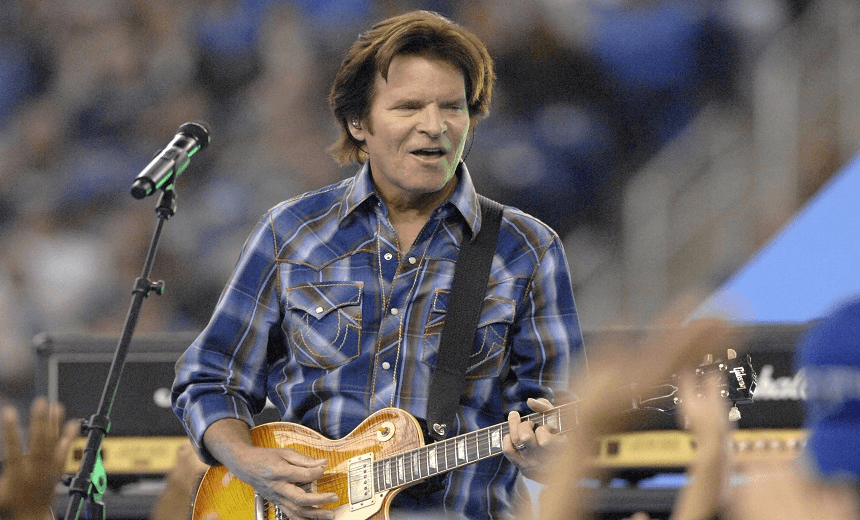

John Fogerty wasn’t the only member of Creedence Clearwater Revival – he wasn’t even the only Fogerty – but the meticulous perfectionist was the band’s guiding light and driving force. CCR fan and New Zealand author John Summers writes on Fogerty’s memoir Fortunate Son.

The room looked out to a grass quad, a sunny spot among the university’s brutalist towers. In the quad, people played hacky sack, they walked hand in hand. In the room we all sat around a plastic veneer table, trying to maintain our head-nodding seriousness as our tutor talked about the Jindyworobaks, an Australian literary movement from the 1920s.

The Jindyworobaks sought to create a new, uniquely Australian tradition. No longer would they ape the forms of old England. Instead they celebrated the bush, the outback and Aboriginal culture.

‘They were all talking and writing about the outback,’ the tutor said, ‘but most of them were very urban, living in Sydney and Melbourne.’

We laughed, enjoying this example of red-handed playacting. But our laughter was interrupted by the scornful words of a young man, an American exchange student, at the opposite end of the table.

‘That’s like that band,’ he said. ‘Creedence Clearwater Revival. They sing all these songs about the South and the bayou, but they’re all from California.’

Our tutor looked uncertain for a moment, then turned his frown to a look of thoughtfulness. He nodded and continued to talk about the Jindyworobaks. We all turned back to him, quickly forgetting that outburst, a momentary intrusion from the world of classic rock.

At least it looked that way. I for one, wanted to raise a hand, to clear my throat and say, ‘If we could just to go back to that point about Creedence.’

*

Exuberance, catchy riffs and swamp country hokum – I thought everyone must love Creedence. And until that morning I also thought they were a Southern band. But that angry young man was right. Not a single Creedence member was from anywhere near choolgin’ distance of a bayou. Green River was inspired by a park in California and an earlier incarnation of the band had the dubious name The Golliwogs in an attempt to cash in on the British invasion trend of the mid-sixties.

Creedence Clearwater Revival were (like the name Creedence Clearwater Revival which combined the name of an acquaintance, a misheard advertising slogan and the notion of the tent revival), a patchwork thing in many ways, borrowing words and themes, even songs sometimes – they famously covered Suzy Q, Ooby Dooby, The Midnight Special and I Heard it on the Grapevine.

Band leader John Fogerty describes this mix of influences in his autobiography, Fortunate Son. Written in a sort of breezy dictation, liberal with exclamation marks (they’re even scattered through the photo captions), he is at his best in discussing his musical inspiration. The first of these being a record of Stephen Foster songs. Foster, he writes, might have been the writer of quintessentially Southern ditties like Oh! Susanna and Campton Races, but he came from Pittsburgh. Without ever visiting the South, he was able to tap into the tropes of the region to create simple songs that, a century and a bit later, are still a part of American culture.

‘I was gonna somehow combine rock and roll with Stephen Foster,’ Fogerty tells us. While later he offers another explanation for his sound, suggesting that he might have been reincarnated, a Southerner reborn to two alcoholics in El Cerrito California, that idea of influence is probably the safer theory. For as much as Creedence is a band of the late sixties, part of the line-up at Woodstock and a staple of Vietnam film soundtracks, they were looking further back for their influences.

Fogerty makes the odd reference to his contemporaries. He’s scathing about the Grateful Dead and respectful of the Beatles, and there’s a great description of running into a cheerful Jim Morrison at a party. But it’s the bluesmen, country artists and rock and rollers of the 50s and early 60s, that he talks of with real reverence. Southerners like Lightnin’ Hopkins, Hank Williams, Duane Eddy and Little Richard. Booker T and the MGs is his pick for the greatest band of all time.

Those earlier acts were the competition, and Fogerty was obsessive in his efforts to get the sound right, to make perfect rock and roll songs. He listened and relistened to recordings of himself to improve his vocals. He taught himself hybrid guitar picking to properly cover Dale Hawkins’ Suzie Q and he lingered in the recording studio, trying to understand every part of the music making process. In 2000 he was still having guitar lessons.

Fogerty wrote the songs, he arranged, he helped produce and manage, but he wasn’t the only member of Creedence Clearwater Revival. He wasn’t even the only Fogerty – his brother, Tom, played rhythm guitar. That perfectionism and need for control, made for anger and tension. When drummer Doug Clifford’s timing was out on one track, Fogerty laboriously fixed it in the editing room. He then gathered up the many many scraps of tape he had cut, stuffed them in an envelope and hand-delivered it to Clifford’s home.

And while he has struggled with the booze – his wife, Julie, is brought into the book to comment on this – those other staples of rock star life: drugs, groupies and excess, are only distractions from that mission of entertaining. ‘You dare not be stoned playing music around me….How are you going to do your best work stoned?’ he writes. There were several arguments over the band’s desire to travel by limo, compounded when, after he failed to find them a taxi to a New York gig, they ended up walking through a rough neighbourhood and ‘saw some things that were fairly upsetting’.

The arguments and the fraught dealings with Fantasy Records Manager Saul Zaentz is the tragic second act in the Creedence story. Locked into a contract that meant song rights belonged to Fantasy, and obliged to produce more for them, Fogerty has spent decades at his lawyers, fighting the company and, at times, his former bandmates. It completes the arc created by their urgent rise to the top of the charts, their three hit albums released in a single year. And it’s a major chunk of his book. ‘I’m not angry anymore,’ he writes, but he does a good impression, carefully detailing the slights, double crosses and incompetence he endured from both the band and Zaentz over the decades. These spill into footnotes. While he manages to come through all this sounding like a nice guy, albeit obsessive, you’ll need to be a Creedence fan to persevere.

*

I didn’t raise my hand in that tutorial all those years ago and the conversation shuffled on to the far less interesting topic of the Jindyworobaks. As important as they might have been to an Australian identity, the poems struck me as over-earnest, hammering at their thumbs as they appropriated Aboriginal themes to build their new national culture. See, for example, this from Boomerang, by founder Rex Ingamells: ‘This piece of hardwood, cunningly shaped/was curved so evenly while piccaninnies gaped/at a Warrior who chipped at it with pieces of flint/and formed it by meticulous dint upon dint.’

I’ve never gone back to the Jindyworobaks. Creedence, on the other hand, I think I’ll always listen to. Even when political (and it’s easy to forget how political they could be – few rock numbers are as piercing about class as Fortunate Son or Don’t Look Now), their songs work as songs first and foremost. They survived my classmate’s scorn and they survive Fogerty’s painstaking listing of squabbles. ‘About as contrived as the weather,’ rock critic Greil Marcus wrote, and it’s true. Driving, tight, it was music tailor-made for drinking beer and having fun. The bayou might be imagined, but when the acting’s this good it doesn’t matter that the backdrop’s paint.

Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music by John Fogerty (Little, Brown, $35) is available at Unity Books.