An excerpt from an essay by Treaty and constitutional law expert Dr Moana Jackson, taken from Imagining Decolonisation, the latest in the BWB Text series from Bridget Williams Books.

James Cook’s belief that he could take this country for England in 1769 because he had ‘discovered’ it, and the whole discourse in the 1830s about how the Crown should ‘annex’ and treat with us, were based on their assumed right to take over the homes of any Indigenous peoples whom one writer would later call ‘your new-caught sullen peoples / Half devil and half child’.

Initially iwi and hapū were not aware that the different ones would believe such stories and looked to the marae to decide what kind of relationship might be possible. Thus the 1835 Declaration of Independence or He Whakaputanga stressed the self-determination of iwi and hapū but allowed the kind of interdependence with newcomers that is recognised on the marae.

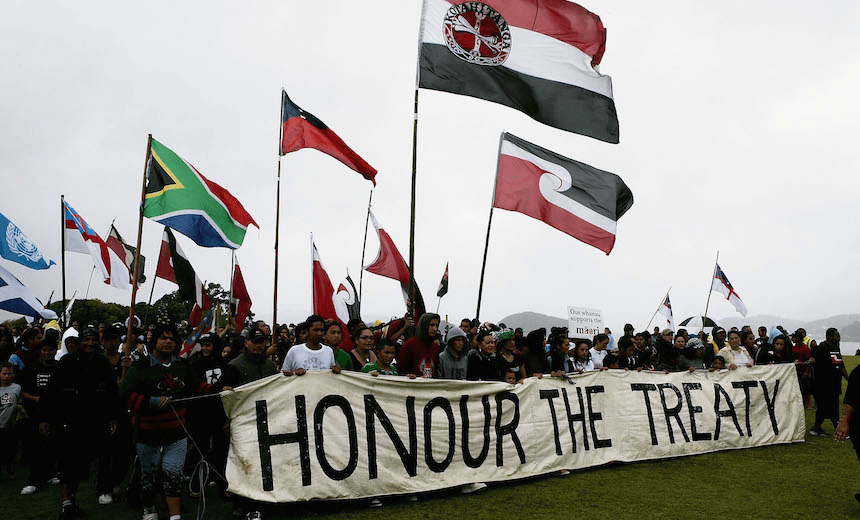

Five years later, when iwi and hapū first discussed whether to treat with the Crown, it was on the basis that the stories in the land could be translated into Te Tiriti as a way to bring people together – mahi tūhono. Like the kawa on the marae, the kawa of Te Tiriti envisaged the cementing of relationships that recognised the facts of iwi independence and the hopes for an inherent interdependence.

The words in the reo in Te Tiriti were an expression of that tikanga-based recognition and were signed by the rangatira on that basis. They reaffirmed that while interdependence was an honourable aim, it was always dependent upon the continuing independence of iwi and hapū. To contemplate forfeiting that independence would have been legally impossible, politically untenable and culturally incomprehensible.

Colonisation had no time for the niceties of tikanga. It fractured the hoped-for interdependence and denied the possibility of continuing Māori independence. The colonisers’ need to impose their laws and institutions on people who already had their own allowed no room for an honourable relationship with iwi and hapū. Instead colonisation fomented injustice: a systemic privileging of the Crown and a relationship in which it assumed it would be the sole and supreme authority.

As they set about ensuring their supremacy through war and all the other brutality of dispossession, the colonisers wrote new stories that deliberately misremembered and obscured the injustice of what they were doing. History became a kind of rebranding in which colonisation was not seen as a violent home invasion but a grand if sometimes flawed adventure that was somehow ‘better’ here than anywhere else because of the proclaimed honour of the Crown in treaty-making.

There is a stark contradiction in terms in the belief that there can be honour in the dishonour of dispossession, and so the new stories never found an easy place in this land. Rather, they sat uneasily upon it like the new place names and fences that were being strung across the new private properties. They were intruder stories on a land that needed no such embellishment.

These colonial stories may have helped explain the taking of power, but they could not give the colonisers the comfort of a place to stand. It was hard to feel at home when the descendants of those who had been killed were never far away and the smoke of the battlefield still lingered in the smoke of the forests that were being burned. In island stories, the intimacy of distance never lets memory entirely fade away.

Other stories had to be told in which colonisation became a wayward and uncertain search for identity. It was often easier just to continue looking back to England as ‘home’ and to turn the valleys and forests and mountains of this land into a landscape that the colonisers could frame and try to keep at a distance even as they took its wealth.

But time gave security if not comfort and eventually the colonisers morphed into settlers and then ‘Kiwis’. They still saw the land as a better Britain in the Pacific, but they increasingly claimed a certain permanence – while turning away from the fact that in settling themselves they were continually unsettling us.

Ownership redefined the tikanga of iwi and hapū relationships with the land, and sexism disrupted the complementary roles of Māori men and women. Racism reduced us to a warrior race or a compliant if noble savage, and arrogance turned sacred and complex understandings of the world into simple myths and legends. The retellings contained little of our truths, instead expressing the coloniser’s belief in our inferiority: ‘Uncivilised folk, such as our Māori, may not do any great amount of thinking.’

In these times of loss and dying, the hope of our independence seemed to fade. The possibility of even an equitable and interdependent relationship with the colonisers receded like the mountains we could no longer touch. People sometimes lost faith in who we once were and might still be, and grew silent with the stories. Yet as the fiercely asserted right of self-determination became a selflessly determined will to survive, the old stories were told in the quiet of the marae. Old memories and histories were sung for those who would come after, and the joy of resilience provided comfort as new challenges were faced.

So the stories survived. Just as adaptation to the pressures of colonisation never meant total submission to its presumed power, so the break in the stories’ telling never meant their disappearance or the destruction of the values they contained. They now speak of a defiant resolve that we will never be silent again, and of the certainty that, as whakapapa carries the past through the now-time, justice will re-emerge in the relationship offered through Te Tiriti.

Imagining Decolonisation is out on March 9 featuring writers Bianca Elkington, Moana Jackson, Rebecca Kiddle, Ocean Ripeka Mercier, Michael Ross, Jennie Smeaton, Amanda Thomas.