The increased presence of anti-trans and white supremacist stickers around the University of Auckland campus is proof that inaction is enabling hate groups, write Anisha Sankar and Max Whitehurst.

Anisha Sankar is a Chennai-born, Te Awakairangi-raised, South Indian Tamil studying at the University of Auckland. Max Whitehurst is a transgender Pākehā student at the University of Auckland.

Last week the University of Auckland became a site of conflict in response to a wave of stickers plastered all over the campus. The stickers were aimed at recruiting followers to a white supremacist group and vice-chancellor Stuart McCutcheon initially failed to condemn or remove them, citing the group’s right to “free speech”. An open letter signed by more than 1,300 people (including senior staff) and an entire week of protest, led by mostly by Māori, Pasifika and students of colour, culminated in a takeover of the university clock tower lobby.

The very same week, another set of disturbing stickers started popping up around campus. These stickers espouse anti-trans rights views, masquerading as “feminist” rhetoric, so they get little attention from passers-by. Labelling anti-trans rhetoric as feminist obscures the intent of these stickers, which is to ridicule the identity, struggles, and existence of trans people – trans women in particular.

Both sets of stickers have been popping up in the same locations on campus, during the same time period, and it is unclear whether or not this is a coincidence. It doesn’t feel like a coincidence, however, that the anti-trans rights stickers coincide with the upcoming public tour of anti-trans groups that will be hosted by Massey University and various Auckland Council venues.

It is clear that in both cases the stickers target some of the most vulnerable groups in Aotearoa. It’s also clear that the institutions which should be responsible for dealing with these issues have instead chosen to protect the rights of hate groups, at the expense of the safety of those who they target.

When students at the University of Auckland demanded that the vice-chancellor be accountable for upholding the safety of students following the March 15 white supremacist attacks, he denied there was any problem. In April he dismissed the claims of white supremacy on campus as “utter nonsense”. Now that evidence of white supremacy on campus has resurfaced in more explicit ways, the vice-chancellor has changed his position, calling the presence of white supremacy on campus “unfortunate“. It was only after media attention and public pressure that he issued a revised statement which said that security would now take the stickers down.

The revised statement, however, still manages to protect the rights of the hate groups. In it, the vice-chancellor was clear that the groups on campus were protected by free speech. In any case, his revised statement comes too late, with explicit white supremacist views quickly gaining momentum on campus.

When students turned to the university for support, it refused to take responsibility, putting the burden of action on those groups who are most vulnerable, forcing them to fight for their rights to live without fear.

Just this week, we have seen the same institutional cowardice from Studio One Toi Tū, a public art space in Ponsonby, after we appealed to them to de-platform an anti-trans rights hate group set to appear there under the banner of an event called Feminism 2020. The venue was approached by various members of the trans community who were concerned about the impact that hosting such an event could have on the community’s wellbeing. They know all too well the relationship between anti-trans rhetoric and the violence trans people encounter in their lives.

Studio One responded to the appeals by saying they did not support or endorse the views of the speakers at the event, yet still fell back on arguments about their right to free speech. The location of the event was moved to the Western Springs Community Hall, another Auckland Council venue. Council made this decision, they said, because they wanted a safer and more appropriate venue in case groups decided to protest against the anti-trans rights group.

The response from the vice-chancellor and the response from Studio One and Auckland Council are uncannily similar. In both instances, they have taken for granted the safety of the most vulnerable members of their communities, and instead prioritised the “free speech” rights of those who hate them.

Feeling unsafe is informed by the likelihood of experiencing violence. In the case of white supremacy, we know that there has been a steady series of events following the March 15 white supremacist attacks that have threatened the safety of Muslim and other racialised minority groups. For many migrants of colour, instances of abuse have become more frequent, not less, since March 15.

In the case of trans communities, discrimination also has very material consequences. The Counting Ourselves report reveals that trans people in Aotearoa experience extremely high rates of psychological distress compared to the rest of the population. Those who had faced discrimination for being trans or non-binary were twice as likely to have attempted suicide in the last year. In addition, trans and non-binary people face a much higher rate of sexual violence than cis women or men in the general population.

What the stats above show is that in a rising climate of anti-trans rhetoric there is a direct correlation between anti-trans ideas and the violence trans and non-binary people face. The spread of these ideas normalises the hatred and violence that these communities endure. Against a backdrop of violence, hiding behind the “free speech” claim to refuse to intervene is itself a form of action. Indifference has always been complicit in oppression. The “free speech” argument, then, allows the relationship between harmful ideas and the violence they incite to flourish. One example of this: the current wave of anti-trans rhetoric has resulted in the deferral of the amendment to the Births, Marriages, and Deaths Act, which, if passed, would give trans people the right to self identity their correct gender on their birth certificate. This would allow trans people to have dignity, privacy, and reduce the discrimination they can face.

The “free speech” argument in both contexts has centred the voices and experiences of those who are perpetuating harm, in turn defending their right to do so. Our institutions must learn to instead centre the voices and experiences of the people who have been, and will be, harmed by hate. When institutions invoke the right to free speech they derail the conversation from the real effects of white supremacy or anti-trans hate speech. For example, after the vice-chancellor’s response to the white supremacist stickers gained traction in the media, the University of Auckland’s Debate Society decided to host a debate on the role of free speech at universities. This mimics the institutional de-centring of those harmed. The debate should instead have been: ‘How harmful is white supremacy?’

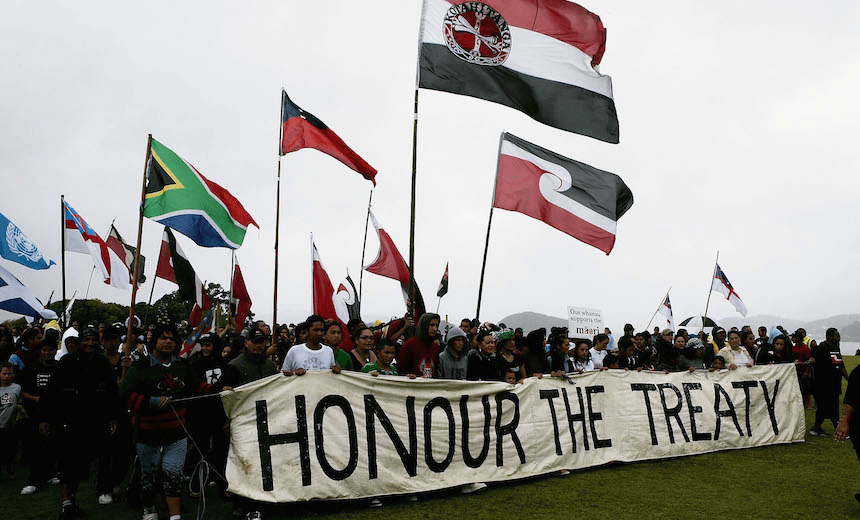

The rise of these groups on the University of Auckland campus demonstrates that all struggles against hate speech are intimately connected. When people coming from marginalised communities try to speak up for the right to feel safe from rhetoric which helps normalises violence, institutional cowardice allows those perpetuating harm to operate as before.

It’s more important than ever to band together in solidarity to fight for the right to feel safe. We are, of course, stronger when we recognise that our fights are one and the same.