Indigenous peoples throughout English-speaking countries have had their children taken away by the state for generations. Most countries have faced up to this legacy but New Zealand has been in denial about its own Stolen Generation – a group now known as Ngā Mōrehu (The Survivors).

The new Labour government has agreed to set up an inquiry into historical abuse of children in state care between the 1960s and 1990s as one of its priorities in the first 100 days.

In this three-part series we look at stories from New Zealand, Canada and Australia, and ask what New Zealand can learn.

In part two, the man who uncovered Australia’s Stolen Generations.

Peter Read was standing in the great hall in Australia’s parliament building when Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said sorry on behalf of the nation to Aboriginal Australians for the taking of their children.

“One of the most moving moments of Mr Rudd’s apology was when I was in the great hall downstairs. People were holding up photos of their parents so the prime minister could apologise to Mum and Dad. They never got to hear the apology. They just said, ‘Mum and Dad, he’s now apologising to you on behalf of the government.’ It was such a moving moment to bring along those pictures. So it was terribly important, to relieve people from that terrible shame which they have lived through all their lives, that somehow ‘I was a bad person or my parents were bad in some way’.”

Read, a white Australian, was a leading figure in exposing what had happened to generations of Aboriginal children who were forcibly removed from their families in an effort to assimilate them into white society. The policy had devastating results.

Read was an oral historian and during his work in the Northern Territory he came across Aboriginal people who would tell him of growing up on a mission station. But their accounts were filtered through the brainwashing they’d been fed as children about the reasons for their removal from their families. They were made to feel that their families didn’t want them or they were unfit.

“They either believed their parents didn’t want them, their parents were dead, or maybe their parents were drunk, or ‘I’ve been naughty’ without realising that wasn’t the case necessarily.”

Neither Read nor his informants had any context with which to frame their histories. It wasn’t until he started looking into the government archives that he realised the individual stories were part of something bigger, something he describes in one of his books as “nonchalant wickedness”.

“I didn’t realise the sensational nature of the story to be honest because I was more concerned with the individual people, some of whom I knew already from my work, or I’d met their parents or grandparents in the course of traveling around the state. The enormity of what was going on did take a while to sink in, partly because I was so concerned about the individual stories.”

Even the way he would explain it to others was in individual terms.

“When I showed this to friends who hadn’t been working in the archives with me I wasn’t saying, ‘Look, there was this policy designed to put an end to Aboriginal culture’, it was, ‘Look at this woman. Some files just say she finished up in an asylum in 1923 aged 38. No more was heard of her. The file just ends there’. I’d say, ‘Look at this for goodness sake, these people are being driven mad by the state’.”

“It wasn’t really until I was asked to publish a summary for a little government organisation called the Family and Children’s Service Agency. I did it and that became the pamphlet The Stolen Generations, which the government printed.”

“I realised there was something more than a whole heap of individuals who are crushed and broken, but also the enormity of the policy of the government which was designed to put an end to people’s Aboriginality, even at the cost of the people themselves.”

The name Stolen Generation was jointly coined by Read and his wife, Jay Arthur. At first he referred to those taken as the Lost Generation. His wife said to him, ‘These children weren’t lost, they were stolen.’

“I said, ‘you’re right.’ So we called them the Stolen Generation.

“That was a phrase which I’m happy to say entered the language and the national currency. It’s still contested a bit, I would say it’s Stolen Generations plural, not singular. Once people grabbed hold of it, it became part of the national conversation.”

When Read started drawing attention to what had happened, it caused consternation in government circles but never any outright denial.

“The state governments, the officials involved in state welfare were not impressed. In fact, the people that asked me to write the paper were not impressed at all.”

“When it first came out I was surprised to find out that the policy had no defenders. Where were all these officials? They all ran for cover. Nobody came out and said ‘this is bullshit’, or ‘we thought we were doing the right thing’. They just ran for cover.”

He was at a meeting of Aboriginal leaders with Coral Edwards, a woman who he had helped find her family and who set up Link-Up to help others do the same. They were in a social setting when she began to explain the work they were doing.

“She started to tell the story. This was before the Stolen Generation as a phrase or a concept was at all well known.

“You could see around the room people thinking, ‘Really? Was that what my mum was always banging on about? That’s why I was taken away. Is that why my brother got taken away? Is that why there was such a fear of the welfare officers? We didn’t realise that.’”

He says giving Aboriginal people the larger narrative about what happened to them was an important part of breaking the silence that had been imposed on them through shame and humiliation.

“They were so ashamed on behalf of their parents who hadn’t looked after them properly. This release from shame, that’s the important thing, this release from shame by having the knowledge.”

That broadening knowledge and public awareness culminated in an inquiry by the Australian Human Rights Commission, which was called by the attorney general. The resulting report, Bringing Them Home, was released in 1997.

Unlike Australia and Canada, New Zealand has so far refused to hold an independent inquiry or offer a government apology. Chris Finlayson, New Zealand’s attorney general under the last National-led government, attacked a draft report written by the New Zealand Human Rights Commission in a letter to the chief commissioner. He focused particular criticism on the report’s call for an independent inquiry. The report was never officially released, although it did eventually surface in media coverage.

The concept of stolen generations is still perceived as something that just happened in Australia. This is possibly because taking Māori children wasn’t explicit in legislation or policy. While both Canada and Australia had official policies and even laws focused on the removal of indigenous children, New Zealand’s case isn’t so clear-cut. There’s no smoking gun that shows that was the intention.

However, New Zealand didn’t have an explicit policy or law banishing the Māori language either but it happened systematically through teachers banning it in the Native Schools and punishing children who spoke it.

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, says the lack of explicit policy doesn’t mean New Zealand can deny that indigenous children were targeted.

“Even if there is a lack of explicit policy, if the actions that have been taken are similar, then we can say it’s a parallel. It’s really the act that is more important than even the policy. In some cases there are policies. But what is even worse is if there are no policies but the actions that have been taken are basically the same in nature. So you cannot say because there was no explicit policy that it never happened.”

What she has noticed working in different countries where the removal of indigenous children took place is there are similar outcomes in those societies.

“When I did my official visit to Australia a few months ago that was one of the issues that came out very strongly. Even after the inquiry that was done on the Stolen Generations, the situation hasn’t really improved very significantly.

“I went to the detention centres, the child detention centres and what I saw was that a lot of the kids were actually coming from foster homes where these kids were taken away from their parents and in some of the cases the parents were also the victims of the Stolen Generation. So somehow this phenomenon continues.

“I was just in Canada recently and spoke at the assembly of First Nations, their general assembly and that was an issue that came up again, about the consequences of residential schools. Willie [Wilton Littlechild] was there, he spoke about his own experience, because he himself has been through these residential schools. There was another report that came out there saying the disproportionate representation of the First Nations in the jails is really alarming. While the First Nations peoples compose 4.5% of the population of Canada, almost 70% of those in the jails are people from First Nations.”

Māori also have high rates of incarceration, with just over 50% of the male prison population being indigenous despite Māori making up about 15% of the population. For Māori women the rates are higher. Government agencies don’t acknowledge the possible connection between high rates of Māori going through welfare institutions and other negative social statistics. Political rhetoric around subjects like crime and incarceration is more likely to focus on gangs. However, Judge Carolyn Henwood, the chair of the Confidential Listening and Assistance Service panel that heard from more than 1100 people who were abused in state care, pointed to Māori gangs originating in welfare institutions in the 1960s and 1970s.

Read believes the continuing presence of indigenous peoples creates a problem for countries built on colonisation and they try to eradicate that presence in other ways. Like taking their children and trying to assimilate them into the dominant culture both biologically and culturally.

“In colonising countries it’s the shame of having indigenous people still around to remind you that the country was invaded. They were a constant reminder and shame that the colonisation of Australia was not as complete as it was supposed to have been.”

He says in certain areas where Aboriginal populations were growing, children were targeted for removal, particularly if the children were of mixed race. The logic was they were a combination of the worst in both races and had to be controlled and assimilated.

Read says the tendency of colonial countries to remove indigenous children has deep roots in the practices of the British Empire. A report about indigenous residential schools presented to the UN drew a similar conclusion.

“Relocation of children is a pretty old aspect of British history. British kids were moved out of London to build up the colonies. They need some labour. There’s too many kids in London, they’re the future delinquents, let’s get rid of them, take them out to the colonies. They did the same thing with convicts. The year convict exports ended in 1860s in Western Australia, the very next year was the year children started to be exported in large numbers. There was a labour part, but it’s very significant. It’s not an uncommon British practice to clear kids out for a variety of reasons.”

“You can see it clearly in the Northern Territory where the girls were being removed in order to be house girls, domestic servants, the boys were being removed to be cattle workers.”

Read believes there needs to be a deeper understanding of the connection between the colonial past and the Stolen Generations.

In Australia, as in Canada, what happened to the Stolen Generations is now included in the history books and school curriculum, rolling back an ignorance that has hidden the impact on indigenous people.

“That’s the big breakthrough as I look back now. So much of our terrible Aboriginal history is still argued about. But the Stolen Generations has made it to the national consciousness, the national imagination, and most importantly the national curriculum. Basically it’s like the First World War – it’s part of our curriculum, it’s part of our history. Even the federal government doesn’t argue anymore that it shouldn’t be on the curriculum.”

New Zealand is only now starting to officially recognise the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s, with a new national annual commemoration as the result of a petition by Otorohanga College students.

But recognising that the removal of children and their abuse in state institutions might be part of the same narrative is a long way off. The subject of abuse in state welfare institutions has only recently gained renewed public attention in the media. But the prevalence of Māori in those institutions is treated as a peripheral issue.

Read says recent immigrants to Australia from volatile parts of the world can be dismissive of indigenous rights.

“If you talk to a lot of non-Anglo Australian [migrants] they’ll say, ‘we’ve been invaded 12 times, what’s wrong with you, get on with your lives.’ But I think everyone agrees that it’s not right to have your children taken off you for an ideological reason. On that one everyone can agree.”

In fact, everyone has agreed. The UN definition of genocide includes acts intended to destroy a group. One of those acts is described in Article 2e: “Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Cree Canadian lawyer Wilton Littlechild has worked in various UN forums for 40 years and says countries that grew out of colonisation are extremely reluctant to acknowledge this aspect of the genocide definition because they know they are exposed. He says some people are more comfortable qualifying the term by calling it cultural genocide, but he says in some ways this dodges the question.

“Was it or is it genocide? We’re told, ‘well yours wasn’t genocide because they didn’t have these outright killings, you weren’t shot to death, butchered.’ But in some cases people argue it’s just as bad, it’s a slower death, a psychological death through these policies, which is still at the end of the day applicable under the definition of genocide. But we’re not quite there yet. I don’t sense personally we’re there yet.”

Tauli-Corpuz says the institutional abuse that indigenous children have suffered contributes to the appalling statistics that plague indigenous peoples throughout the world.

“There needs to be a lot more research and analysis done. At least from what I have seen, where children have been systematically taken that is where you see these kinds of results: high youth suicides, disproportionate representation in the jails, even violence against women and children. These are some of the consequences.”

In August, New Zealand appeared before the UN’s Committee on the Eradication of Racial Discrimination. The committee expressed alarm about the abuse of Māori children in state institutions and called for the New Zealand government to “immediately set up and empower an independent commission of inquiry into abuse of children and adults with disabilities in state care from 1950 until 1990, with the authority to determine redress, rehabilitation and reparations for victims, including an apology from the State.”

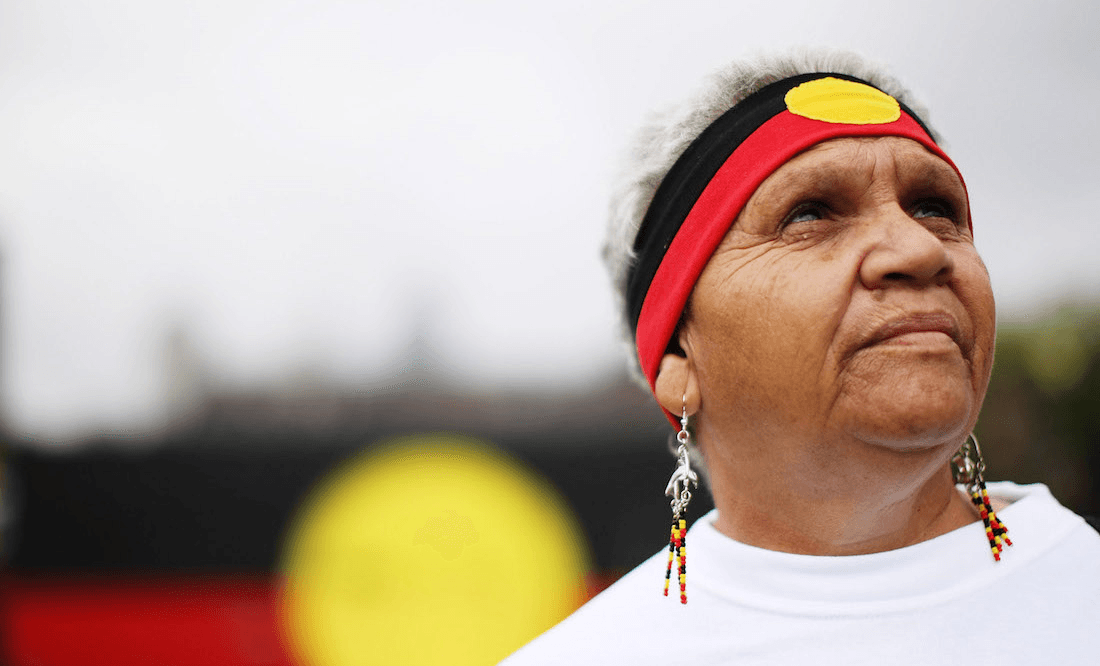

Feature image: Joan Baker, daughter of Ruby Williams who was taken from her family at three years of age, watching the live televsion broadcast from Australian Parliament in Canberra as Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd delivered an apology to the Aboriginal people for injustices committed over two centuries of white settlement on February 13, 2008 in Sydney, Australia.

Aaron Smale @ikon_media

〈 Click here to read part one: A shameful legacy

Click here to read part three: A slow genocide 〉

A version of this story also appears on AlJazeera.com