After a cowardly attack on a pouwhenua in Lyttelton, Te Kuru o Te Marama Dewes talks to carver Caine Tauwhare about what it meant to the community, and imagines a visual landscape where cultural markers of mana whenua are as abundant as Cook statues.

Driving through most cities in Aotearoa, you wouldn’t even know you’re on Māori land.

Yet, growing up in Rotorua, I was surrounded by a visual landscape that embraced its whakapapa Māori. The region is populated with intricately carved marae and an abundance of Māori sculptures in public areas.

Tourism definitely played a big part in the expression of Māori culture in Rotorua, supported by the strong whakapapa traditions in carving that continue to flourish. They weren’t everywhere, but Māori designs were part of the visual landscape.

As I grew older I realised this did not extend to other towns or cities in Aotearoa. Pou whakairo are often lone landposts in an otherwise concrete jungle; aging stonework facades of storied buildings, wrapped in billboards for the likes of property companies.

This is slowly changing. Pou whakairo are being erected across the motu to mark mana whenua pā sites and wāhi tapu, to reaffirm the places and spaces we inhabited that have so often been paved over in the cities, or trampled on by cows in the regions.

But it’s clear not everyone is ready to accept the reaffirmation of Māori in our visual landscape.

Follow The Spinoff’s te ao Māori podcast Nē? on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

The violent cutting down of a pou whakairo at Ōtūherekio in Te Waipounamu should serve as a stark reminder for non-Māori of the unresolved layers of racism in Aotearoa.

“It’s a really sad reflection that we still have to experience this sort of hatred and cowardice in our country, especially in regard to recent events that we’ve suffered here in Christchurch with a similar type of hatred,” says carver Caine Tauwhare (Tainui, Ngāi Tahu).

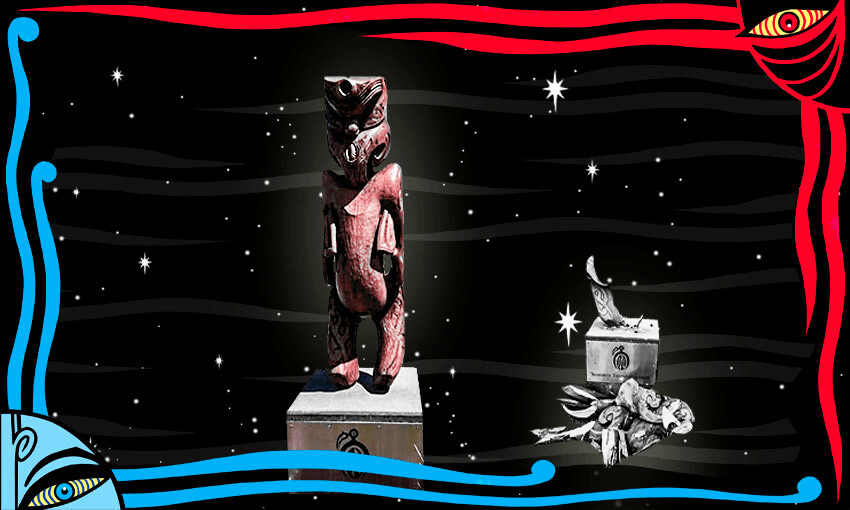

The pou, Te Kōauau o Tāne Whakapiripiri, was one of a number carved by Tauwhare and students of the Whakaraupō Carving Centre Trust. Through the installation of Māori sculptures by the local carving school, the visibility of Māori culture in Ōhinehou (Lyttleton) has grown over the years.

“We’re seeing not only the whānau showing a new sense of pride from seeing our tīpuna on the ground in this form, but Pākehā are really embracing it too,” says Tauwhare.

The pou was installed at a traditional Ngāti Wheke pā site at Ōtūherekio, where mana whenua would welcome manuhiri to their pā.

Ōtūherekio, as it was named by Māori, is now commonly referred to as Pony Point. It’s flanked by Cass Bay, which was originally named Motu-kauati-rahi.

“The residents of our bay next door, largely made up of Pākehā, fell in love with the pou up there. I would always get comments from people about how much they enjoyed it. They certainly showed care by cleaning it and planting around it,” says Tauwhare.

The pou whakairo itself embodied genuine attempts by Māori to welcome non-Māori with open arms to their whenua and strengthen that relationship, despite the ongoing impact of colonisation.

“The violence that was carried out on this harmless pou, this piece of wood if you like, is very disturbing, and hopefully whoever is responsible gets the help that they need,” says Tauwhare.

“I’m really mindful of the potential of where it could go,” he adds, alluding to the rise of white supremacist sentiment in the wake of the Christchurch terror attacks.

The desecration of Māori pou isn’t new. In 2019, two pou were hacked down in Ahipara. In the same year, a whakairo in Tararua had its phallus removed with a chainsaw by an elderly Christian man claiming he was doing God’s work.

The motive for the latest act of violence is unknown, but it speaks to unresolved racist attitudes towards Māori and a deep insecurity around Māori receiving what was promised by the Crown in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In Tūranga Nui a Kiwa, Gisborne, where Pākehā first arrived in 1769, pockets of the region still cling to the colonial heritage of Captain Cook. Like many rural towns, the architecture is largely colonial and the presence of Māori design is minimal.

Formidable monuments glorifying Cook’s landing cement Pākehā presence in the visual landscape, in spite of the disdain from mana whenua for the former British naval officer who was responsible for the death of nine tīpuna Māori upon the arrival of the Endeavour.

But local Māori artists are pushing to affirm Māori presence there. The local court house, airport, council and hospital all have notable installations which add cultural value to their surroundings.

A more recent response, led by artist Nick Tupara of Ngāti Oneone, has attempted to balance the colonial narrative with a large iron monument honouring his ancestor Te Maro who was one the nine Māori killed. Below at ‘Cook’s Landing’, Tupara has overseen the creation of a wānanga space Puhi-Kai-Iti that represents the mooring of the original waka in the area.

Colonial statues are visual assertions of settler power, markers of land confiscation, and create a false narrative of Pākehā dominion. Māori public art and installations, on the other hand, are often inspired by stories of unity, like Te Kōauau o Tāne Whakapiripiri, and tend to not only improve the visual landscape but bring people together.

While the increasing presence of Māori design is promising, it can still feel tokenistic. Māori designs are often added to Western structures, like a corporate meeting room with a Māori name, or a bridge with a Māori design on the side. I want my mokopuna to live in a world with unique Māori architecture, created solely by Māori artists and designers, to reimagine our pā in the 21st century but with the sustainable values of our tūpuna.

I don’t need to look far from home to see that potential beginning to be released. Te Tairāwhiti Arts festival has just wrapped for its second year, and the main attraction, Te Ara i Whiti, is an interactive pathway of various Māori light-forms on display for people of all ages and cultures. It’s like a futuristic Māori village with lights, art, music, food, dancing and whānau.

It’s a highlight in the calendar and a taste of what the present could have been if Māori weren’t forcibly removed from their whenua while the land itself was redesigned to replicate various British layouts.

Seeing our culture represented in the visual landscape is a friendly reminder that we exist. It’s a reinforcement of who mana whenua in the area are. It reminds non-Māori where they are. It reminds us all that this whenua has a rich history of sustainable architecture and design that existed and thrived for over a thousand years before the arrival of non-Māori.

When we imagine what an inclusive and unique vision for the future of Aotearoa looks like, we need to base that on the strong cultural foundations that are embedded within the whenua.

As Caine Tauwhare says: “It’s important to represent our tūpuna, and those tikanga that our ancestors were about to be really in harmony with the whenua.”

It serves as a reminder to all those living in Aotearoa, no matter where you are in the motu, what you see is Māori land. Always was, always will be.