Māori, Pacific and low income groups have health outcomes well below the rest of the population. In Dunedin there’s a community that’s come up with the medicine to treat itself.

On the grounds of an old school in the South Dunedin suburb of Caversham, there’s a village of healthcare services that’s a vision into a traditional Māori understanding of the world, which offers a view into a future where better health outcomes for Māori, Pacific and low income families are the community’s responsibility. A wrap around state-of-the-art health hub, Te Kāika, (“The Village”), is about providing the demographics neglected by New Zealand’s healthcare system a place where they can get well, and learn how to stay well.

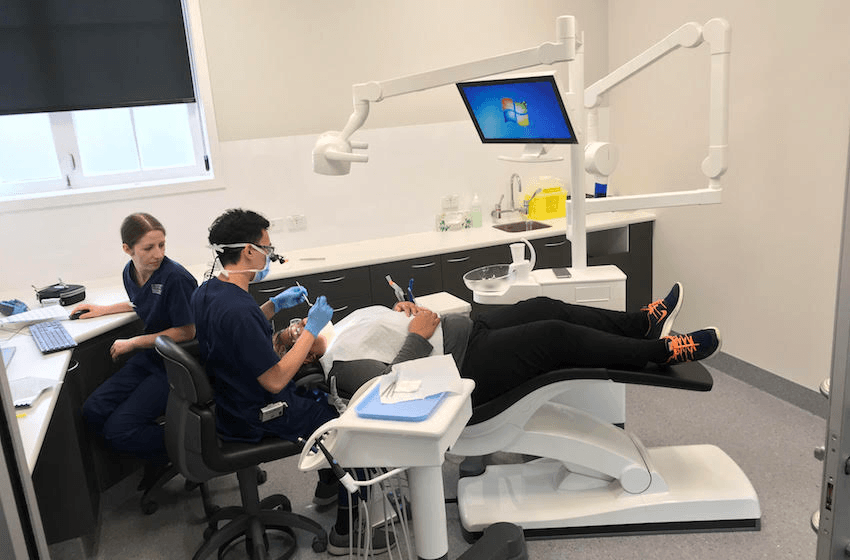

Te Kāika was four years in the making, but in the few months since it opened its doors it’s become an essential place that sits at the heart of the local community. There’s a GP practice, with two doctors and four nurses, a dental clinic where University of Otago final year students receive a unique cultural education, a gym, and teaching spaces. And there are even bigger plans.

Just ten days after opening there were 800 registered patients, and at last count nearly 2000 locals enrolled. With around 58% of patients being Māori or Pacific, who are classified as “high needs” by the Ministry of Health populations, Te Kāika qualifies for Very Low Cost Access support to help maintain low fees. A GP visit is $18 for an adult, and free for children, and the dental clinic offers low fees at the same rates as the University of Otago School of Dentistry.

And it’s so much more than a health centre. Te Kāika is the vision of Donna Matahaere-Atariki, chair of Te Rūnanga o Ōtākou, and Albie Laurence, the former chair of the health organisation Pacific Trust Otago. They’d been drawn together over a mission to help communities take the lead in changing their own health outcomes. They wanted to provide primary care services that were empathetic, affordable, and culturally responsive, while removing barriers to seeking health care. They wanted to build a place the community would gravitate to, rather than be intimidated by, a place where they would find sanctuary and understanding, and a place where all its members could contribute. Its principles are founded in te ao Māori, in the idea that everyone is invested in the health and wellbeing of their community.

“Te Kāika is a village [with] a range of services and facilities that are about building community, ensuring the community receive their citizenship entitlements and building a shared responsibility for wellbeing. Once our gardens are completed it will also be a place where community can come, not just for a service, but to meet each other to sit in lovely surroundings, have children using the playground and build understanding, tolerance and closeness. [We want to] encourage and model a sense of responsibility towards each other,” says Matahaere-Atariki.

Te Kāika was inspired by their experience meeting people abandoned by the health system. People like a Māori man, newly arrived in Dunedin and in need of treatment, who’d been refused enrollment at GP clinics because of a history of outstanding payments. They found families spending hours at emergency clinics for ailments that could have been seen by their local doctor. As a health manager working in a Pacific communities, Laurence constantly found health services in Dunedin were too expensive for the groups that he worked with. In her work with Māori communities Matahaere-Atariki encountered a deep sense of despair in whānau constantly unable to realise their potential. She was determined to push back against the tide of inequities that determine outcomes for Māori and Pacific communities.

“I think you start from the basis that if you address the environment that produces inequity, that builds an industry on the backs of deprivation, you come to a realisation that it is just not possible to be a ‘saviour’. Change must come from people themselves. Our job is to focus on the environment that enables others to make good decisions for themselves,” she says.

They wanted to challenge the institutional inequities in the healthcare system by challenging the system itself. And this starts with acknowledging where the inequity comes from.

“On a structural level, discrimination exists when specific group interests are represented and others aren’t. At an operational level these same institutions construct policies and practices that benefit themselves, that look like them and that view others different from this dominant group as ‘’lacking’. At an interpersonal level this ‘lack’ is then transposed onto Māori and other groups as somehow the result of culture,” says Matahaere-Atariki.

“Culture misinterpreted is always minimised to be about life choices or lifestyles, so that the issues of ill health, poverty and inequity can be blamed on individuals.”

To change the outcomes for the community required buy in from the community. The roll call of people and organisations required to make Te Kāika possible is long, and a symbol of the broad village the initiative represents, and the partnerships required to start engaging marginalised groups in the health system. It was about unlocking the resources of Dunedin – its local iwi, and its oldest institution, the university.

The initial start up funding came from Te Putahitanga o Te Waipounamu (the South Island Whānau Ora commissioning agency) and Ngāi Tahu. The iwi asked the university, as a good Treaty partner, to invest in the project; the university is now a shareholder. The village is overseen in partnership between Arai Te Uru Whare Hauora, Te Rūnanga o Ōtākou, and the university.

“The University of Otago investment was huge in enabling us to open our doors. The major hurdle to creating Te Kāika, and the reason we don’t have hundreds of Te Kāika throughout New Zealand, is that to start a village you need a lot of start-up capital,” says Laurence.

Te Kāika is also designed as an essential teaching environment for University of Otago students to learn about the unique needs – cultural, emotional and physical – of Māori, Pacific and low-income patients. The staff at the clinic reflect the communities that they work with, and all the teaching and research staff follow the cultural policies of Te Kāika.

“It’s a completely different environment to when they are working in the university environment. They believe they can treat students in various professions to work effectively with Māori, Pacific Islanders and low income communities. It is a bit of a paradigm shift to what many would think is normal,” says Laurence.

It’s not only an opportunity for the health professional to understand a new way of thinking about the people it looks after, but an environment where the community can learn about how to look after itself. For this experiment to succeed, the community needs to be as equally engaged in the village, as Te Kāika is involved in finding new ways for the system to work. In Matahaere-Atariki’s plans Te Kāika was never just about treating health issues, it was about empowering communities to drive their own wellbeing.

So, Te Kāika combines professional and clinical responsibility with encouraging and educating a population to pursue self-determination. This requires addressing all aspects of their lives and addressing the social factors that get in the way of good decision making, according to Matahaere-Atariki’s philosophy.

“A terrible hangover of inequity is that you have generations of passivity bred into the very fabric of Māori society, a debilitating sense of an ‘acceptance of our lot in life’. Change requires [an understanding] of our predicament and the courage to stand against stereotypes and victim blaming. Māori need to rebuild a sense of personal and social responsibility for leading changes that enrich our lives,” says Matahaere-Atariki.

“To do this we need to address basic entitlement issues, that is what Te Kāika is intended to ameliorate.”

At Te Kāika’s opening ceremony former MP Dame Tariana Turia was a guest of honour and spoke to the large crowd on a sunny February morning. She had dragged herself away from the annual celebration of her Whanagui iwi’s 1995 occupation of Pakaitore to attend the event. In Te Kāika’s investment in the future of the community she saw the same sense of community represented in the occupation of land her iwi never relinquished to the crown. Through collaboration of iwi, institutions, and individuals, Te Kāika is building a village dedicated to the future success of its community, she said.

“What you are doing is premised on the belief that whānau are the source of their own greatest solutions. It is driven by the belief that the building blocks for a stronger future for whānau will be set down by whānau themselves,” she told the crowd.

This content is brought to you by the University of Otago – a vibrant contributor to Māori development and the realisation of Māori aspirations, through our Māori Strategic Framework and world-class researchers and teachers.