The announcement that Auckland University’s arts school is to close its library speaks volumes about the value we place on art in New Zealand, argues Reilly Hodson.

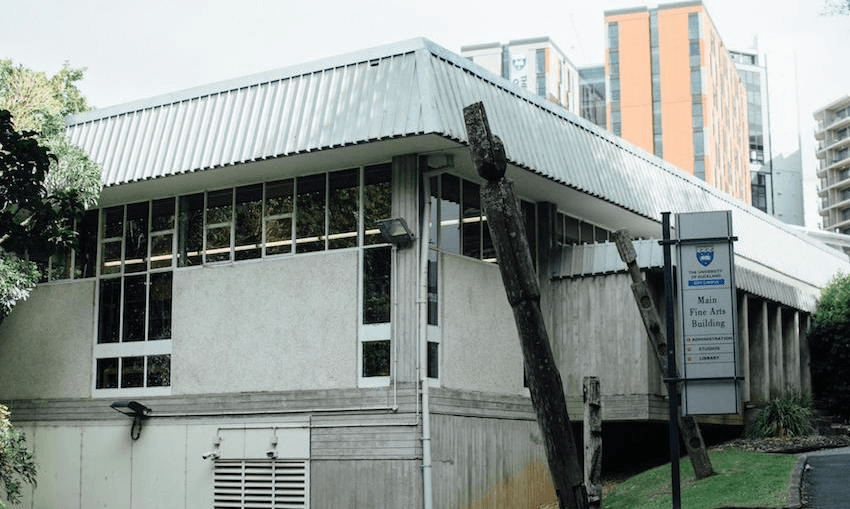

The Elam School of Fine Arts is the pre-eminent art school in the country, and has produced “important” and well-known artists like Michael Parekowhai, Rita Angus, James Lowe and Lynley Dodd. Its library houses the largest collection of fine art books and texts in the Southern Hemisphere. The school itself operates unlike many other university faculties, encouraging creativity and artistic development. It’s also a centrepiece for the artistic community of Auckland and New Zealand, which congregates around Elam and its surrounds.

And, sometime this year, the university is planning on shutting its specialist Fine Arts library, along with those of the architecture and music schools. This is a big deal, and a bad sign.

The Fine Arts library itself is a singular space. It’s a bit old, sure, because the whole art school is the victim of decades of oversight and downright neglect, tucked away down the hill by St Paul’s church. It gets cold in the winter, and a bit stuffy in the summer, but it’s a comforting space. There are little cubbies for people to study in along one wall, and the room is cosy in the way that older libraries tend to be. There are books everywhere, on every kind of artistic discipline. Hidden from view, too, are the invaluable special collections, which contain years worth of ephemera, one-off volumes and other taonga. The collections are cared for and curated by specialist librarians, who are themselves an invaluable resource to students. Elam students I spoke to describe the library as the heart of the community, a shared space where students and professionals alike research and spend time. It’s open to the public, by the way, so you can pop in and have a look even if you aren’t a student.

The decision by Auckland University bigwigs to move the library’s collection to the main library, or to offsite storage – and possibly shred thousands of books – is of course devastating on a micro level. It’s part of a library restructure that will end 45 people’s jobs, and it makes it much more difficult for students to get the resources they need to do their work. Of course, it’s a barrier for students to walk up and down the hill to the main library, but the lack of ability to browse the shelves for the entire collection is the real issue here. A spokesperson for the university told me that books can be accessed from offsite storage by students or staff “usually within a 24 hour turnaround”, but students I spoke to disagreed, saying they often could not get books stored offsite. To relegate much of the current collection to that fate is a disaster for students (and teachers and full-time artists) that want to pursue a less mainstream line of work, and takes away immense amounts of freely available knowledge for anyone that would peruse its shelves.

University administrators have not given much detail on how the decision was made, and it certainly didn’t involve any significant student contribution. In fact, the report on which the University is basing this decision (which you can read here) reads at times like an argument for keeping the library intact. For example, it says the shelves of the Creative Arts libraries are overstocked, which seems to me like an argument to get some more shelves, not to get rid of them. The loan rates for books at the libraries are decreasing, but at a significantly lower rate than the general library’s loans (4% to a general 43% drop between 2012 and 2016). This is despite the fact that most art research happens within the library, rather than loaning out, a type of study that is made extremely easy with the current set up, where the library sits right next to the student studios.

The report also acknowledges that the “information needs of individual artists are extremely idiosyncratic”, which is the best argument that can be made for keeping artistic libraries open, not to relegate much of the amazing collection of the library to offsite storage. Students involved in the campaign to keep the library say that this justification all feels cynical, disguising what appear to be mostly financial decisions with discussion of “student needs”. The report posits that the fact that students will feel a sense of loss about the libraries is a challenge to be overcome, rather than an indication that what they are doing is potentially not in students’ best interests.

All of this leaves a particularly bitter taste in the mouth considering that the libraries to be closed are art-focused, while the law and medicine libraries will stay open. I can’t speak to the importance of physical books in medical study, but I know as a third year law student myself that the very existence of a physical law library is a waste. Near enough to 100% of all law texts and cases can be found online, and are easily user accessible in a way that art texts are simply not. Law students do not have particularly diverse requirements in terms of texts, either. They all use more or less the same information in their studies. There is no reason for any law student to look up a physical law report, but there is real value in looking at the printed page in artistic study. Students at the Fine Arts school that I spoke to found this a particular sticking point, given that their fees, and therefore debts, can be higher than that of a law student, a difference attributed to paying for the resources of the art school.

The library and its resources are a selling point for study at Elam, and post-graduate study in particular requires access to the full extent of these resources, in the same way that studying chemistry requires a laboratory. Honours-level students pay full-time tuition prices despite only having five hours of class a week, and sorely need the library for the full-time self-motivated study that their course requires. The Elam Student Associations told me they’ve got emails saying that students wouldn’t want to return to the school if the library was removed, and certainly wouldn’t recommend it to prospective students. For the university to claim that funding restrictions led to this library restructure while other libraries stay open and new science buildings get built feels like a slap in the face to our art students.

But it’s more than a student issue. The way in which the university has approached this whole situation speaks to a broader disregard for the arts in our national culture, and a dereliction of its own duty as a space of enlightenment for the city as a whole. The fact that almost all at once, the Art Gallery considers charging an entrance fee to overseas visitors, the Auckland Council releases a draft 10-year plan that has no reference to arts or culture, and the University is closing what is both an important space and resource in the Fine Arts library, shows the way in which we as a nation devalue art. We’re so quick to get on board with a bunch of white guys riding some boats very quickly, or to build a new science facility, but when the arts community needs a bit of extra funding, we tell them to get over it, or that they should be glad that they even have the space to exist. New Zealand continues to have a flagrant disregard for artistic disciplines, and the usually intangible benefits they provide. Every time an organisation has some financial strife, arts funding is the first thing to go. Maybe it’s because you can’t “win” at art, or something. But it remains a clear truth that the world class cities and nations on which we should be modelling ourselves are ones that are enhanced by strong artistic communities.

At the moment, that community is bootstrapping, for the most part. Artists get by despite very little public funding, and this consistent apathy towards their work. We’ve created a system whereby artists no longer have simply to make art, we force them to campaign, to justify their existence, to keep their spaces open. Even Michael Parekowhai, one of the few New Zealand artists who has name recognition and access to what funds exist (by the way, an Elam alumnus and tutor), had to justify his own work’s legitimacy to a public that sees public art as a waste.

A student campaign is rising to fight for their right to say what the library means to them, but it says so much about our national approach to the arts that they have to. The All Blacks never have to justify their training grounds, and a scientist would never have to justify keeping their laboratory, so why do we force artists, again and again, to prove that they are worthy of respect?

We need to stop seeing art as a burden, and start seeing it as an opportunity. Yeah, it might not literally save people’s lives or make anyone a lot of money, but art is critical to our success as a society. That the university is looking at a process that will make it more difficult for students and the public to access knowledge about art is a blight on all of us.

You can submit to the Vice Chancellor, University Management and your local MPs at this link, or by emailing savefineartslibrary@gmail.com, and follow the campaign to keep the library open on Facebook.

This section is made possible by Simplicity, New Zealand’s fastest growing KiwiSaver scheme. As a nonprofit, Simplicity only charges members what it costs to invest their money. It already has more than 12,500 plus members who, together, are saving more than $3.8 million annually in fees. This year, New Zealanders will pay more than $525 million in KiwiSaver fees. Why pay more than you need to? It takes two minutes to switch. Grab your IRD # and driver’s licence. It really is that simple.