Teuila Fuatai is introduced to one of the most dangerous stretches of road in New Zealand.

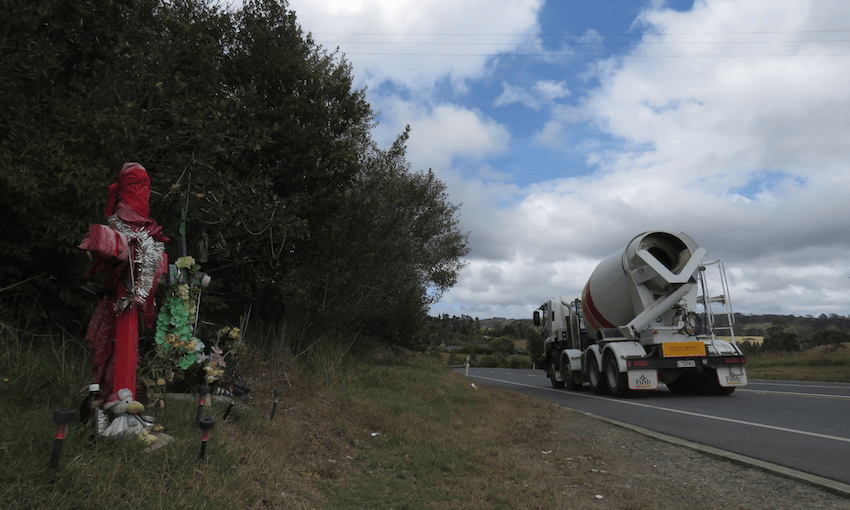

Between Albany and Silverdale is Auckland’s Dairy Flat Highway. The 15km stretch of road used to be how a few local farmers and their families would get around. It was a quiet piece of Auckland’s infrastructure.

Today, it’s a busy part of the Supercity’s growing roading network used by thousands of people and a variety of vehicles each day. But while more people and businesses have come into the area, key roads like Dairy Flat Highway haven’t exactly evolved to match the change in pace.

That lack of roading infrastructure development is reflected in the area’s dire crash statistics. Over the past five years (2014–2018), there were 160 crashes along Dairy Flat Highway. Six people were killed, 22 were seriously injured and a further 85 people were left with minor injuries. The statistics led the Transport Agency (NZTA) to identify Dairy Flat Highway as among the “top 1%” of roads needing investment in improving their safety.

Auckland Transport, which is currently seeking public feedback on proposals to reduce speed limits for the city’s riskiest roads, have also “come to the party” as Rodney local board member Louise Johnston puts it.

At the end of last year, after ongoing pressure from locals fed up with people being killed and hurt on the road, the speed limit along Dairy Flat Highway was reduced to 80 km/h from 100km/h. In some areas, around busy intersections and portions of the road, the limit has been set at 60 km/h. Road safety advocates and locals like Johnston agree that by slowing vehicles down, road users would have more time to negotiate difficult points along the road. Similarly, accidents which did occur were less likely to be as severe because vehicles were not moving as fast.

To understand the dangerous mix of speed, high-traffic and highway road conditions, The Spinoff travelled with Auckland Transport’s engineer in charge of rural road safety and speed management, Michael Brown, to Dairy Flat Highway. Starting at the Albany end, we worked our way towards Silverdale, beginning not far from where Johnny Danger drove off the road and died on Anzac Day last year.

Standing at the point where Danger crashed his motorcycle – also the first intersection on the road – Brown outlines the changes being planned for later this year. The two, uphill northbound lanes, one of which had been partially closed for the afternoon because of a fallen tree branch, are due to be changed to a normal lane and a slow-vehicle bay. The intersection, which requires a gnarly-angled left turn for north-bound vehicles wanting to get off the main road, will also get a spruce up, making it less risky for vehicles turning in and out.

As we watch a few large trucks and motorbikes negotiate the intersection, Brown comments: “You can see that even with the lower speed limit, people still go pretty fast. The changes are designed to slow things down and lessen the risk of bad crashes.

“The slow vehicle bay will probably get a bit of pushback, but it’ll be far better than having people travelling at speed, round a corner and essentially straight into an intersection.”

Further along is the junction with the Coatesville-Riverhead Highway – the second highest-risk intersection in the country based on the number of crashes that have occurred. It has a lot going on with bus stops on both sides of the road and a petrol station. Two nasty crashes in the past two years sparked particular outrage from locals around its messy set-up.

In June 2018, a local teenager was seriously hurt pulling out onto Dairy Flat Highway. A year earlier, it was a crash involving a school bus. Johnston, who spearheaded the campaign to reduce speed limits, said many locals had been desperate for change.

“Cars just go so fast along Dairy Flat Highway, and pulling out onto it, or getting off it, can feel so dangerous at times,” she says.

At this intersection, the 60 km/h speed limit was implemented after the June crash last year.

“That day, there had been an accident on the motorway, so everyone was taking Dairy Flat Highway [as an alternative route],” Johnston says of the crash.

“There was real pressure to come out of the intersection with Coatesville-Riverhead Highway – I felt it when I was trying to drop the kids off at the school bus on Dairy Flat Highway. A young girl, a year 12 girl, actually came out and hit a truck, and other vehicles were also involved.

“As a parent, that could have been any one of our kids, or it could have been anyone. You know when you’ve got a whole lot of cars behind you, and you’ve got to get out, you ultimately do take a risk. People are tooting behind you – and that’s what happens.”

Since the lowered speed limit, crashes have significantly decreased. Later this year, construction of a long-awaited multi-lane roundabout at the intersection is also due to begin. In his hi-vis AT vest, Brown explains why this spot had been earmarked for a whole new layout.

“It’s the sheer number of vehicles coming through it. You could have the exact same intersection in a remote part of the South Island, which only has four or five cars coming through it a day and it would be fine,” he says.

The roundabout, which is costing “the best part of $6 million dollars”, will force drivers coming along Dairy Flat Highway to slow down, making it less risky to pull out of the Coatesville-Riverhead Highway. While there has been some opposition from cycling advocates focused around the risk multi-lane roundabouts have for those on bikes, the planned changes have generally been welcomed.

“We accept crashes will occur,” Brown says. “What we want to try and reduce is the deaths and serious injuries in the network.”

The changes are all based on basic physics. Auckland Transport’s logic is: reduce the kinetic energy involved in a crash and the severity of the forces are going to be lower. Therefore, there’s less likelihood of death and serious injury.

“At the roundabout, when they put it in, there may be more low-speed crashes, because you’re going to have people slowing down and getting used to it. But they’re going to be little fender benders at the back rather than somebody coming out and getting T-boned or a head-on crash.”

Next, we stop at the intersection with Kahikatea Flat road which provides access to the Dairy Flat Village. Brown points to the bakery on one side and notes its “award-winning” pies add to the busyness of everything happening. Opposite is a petrol station with a truckie stop. Today, the road is also lined with cones as general maintenance is carried out.

Like the Coatesville-Riverhead intersection, the speed limit here is 60 km/h. While lorry trucks and cars still hurtle past at speed, both Brown and Johnston agree that the lower speed limit has been a significant step in the right direction.

Further changes to improve visibility, and make turning less risky, are also in the works.

“Even if you go now, and it’s 60 km/h, it’s really haphazard and it’s just quite chaotic. That was 100 km/h last year,” says Johnston. “But people have actually said to me [that] pulling out now onto Dairy Flat Highway and turning right doesn’t feel like a death trap anymore. I’ve had about three or four locals come up to me and say words to that effect.”

As drivers become more attuned to the slower speed limit, the ongoing road changes should also help, she says. At the beginning of this year, not long after the new speed limit was implemented, a crash between a motorcycle and car at the intersection resulted in a woman being hospitalised and the road being temporarily closed.

“It’s just awful when you hear sirens and see the road closed because of another crash. We don’t want more people getting hurt and dying, so changes have to happen,” Johnston says.

She’s also realistic about how things are going on Dairy Flat Highway. What she’s observed as a local resident and board member are indicative of the problems Auckland Transport are dealing with city-wide.

“It’s not actually Dairy Flat Highway,” Johnston said “It’s all the intersections off the highway. That’s why if they’re just driving through, they’re saying well why do we need this to be 80 km/h. Well, it’s not the actual road, it’s the intersections.

“When they designed it to be 100 km/h, we had one or two farms off all the sideroads. Now, all the big farms have been subdivided up and they’re getting further subdivided under the unitary plan. There’s just so much traffic on the roads now and it’s not set up for that.”

She’s aware there are sections of the road locals aren’t happy about, stretches where they argue 100 km/h is safe. But it’s quite difficult if you keep breaking up the road into different speeds, Johnston said.

Currently, the speed limit switches between 80 km/h and 60 km/h six times on Dairy Flat Highway. On the day we were there, a seventh speed limit change to 30 km/h near the Silverdale end was in place for road works.

Brown would like to see roundabouts at all the points “because that’s the safest way to control the turning movement.”

However, multi-million dollar road changes at every intersection are just not a realistic and efficient road safety approach, he says.

“The reality is that we don’t have unlimited money. We have to do what we can with what we’ve got and make things safer.

“Ultimately, it’s about taking a holistic approach to creating more suitable roads for how they’re being used at the present time.”

Lowering the speed limit is one of the most immediate and cost-effective things you can do. Engineering changes – like fixing blind spots and installing roundabouts – are also important, but they take longer. It’s also unethical to allow people to keep driving on roads which can be made safer through more straightforward fixes like lower speed limits.

“For example, at Dairy Flat Highway, if we were going to put wire rope barriers up the entire length, both sides and up the middle as well, it would cost millions and millions of dollars. We’d also have to put in roundabouts and turning bays to break it up. We’d probably get one road done a year if we did that and that’s not really going to get much change.” Brown adds.

And while it was too early for any official analysis on the crash rate since the change in speed limit, Johnston is adamant locals have already noticed a difference.

“At one stage, there seemed to be a crash every week. Now, at the Coatesville-Riverhead intersection, we’ve probably had two crashes in the last eight months.”

“It’s awful that for Dairy Flat Highway to get the speed limit reduced it was because we had all these really bad statistics.

“But now, it just feels safer. It’s going to take a while for driver behaviour to change, to realise it is 80 km/h because people have been in the habit of going 100 km/h, but it will happen.”

This content was created in paid partnership with Auckland Transport. Learn more about our partnerships here.