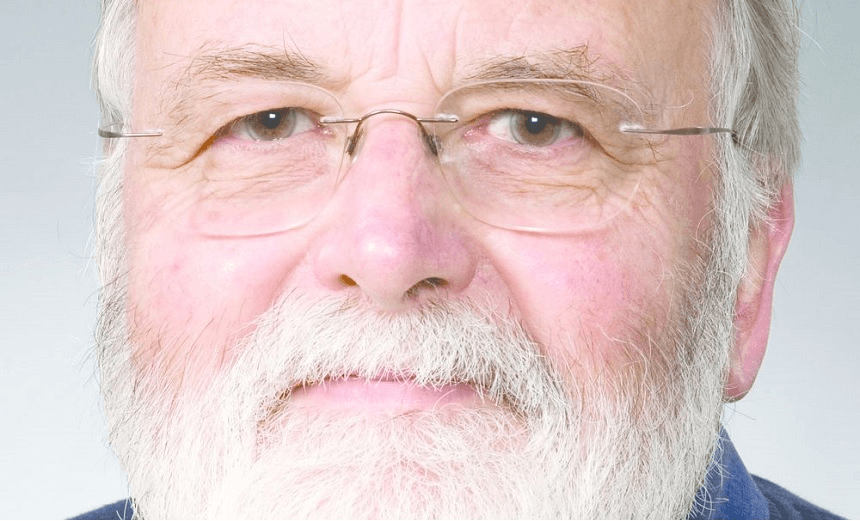

All week this week we focus on books and authors nominated for next Tuesday’s Ockham national book awards. Today: a goddamned epic interview (6000 words!) with fiction finalist Patrick Evans, conducted by Spinoff Review of Books literary editor Steve Braunias.

The live email interview is seldom practised but will revolutionise journalism as we know it, probably. It has the zip and immediacy of meeting IRL with the bonus of a literary dimension – everything is written down, fast, with no possibility of leisurely revision at some later date. On Sunday night I conducted such an interview with Patrick Evans, a finalist at next Tuesday’s Ockham national book awards, nominated for his novel The Back of His Head.

I was at my house in Te Atatu listening to a 1975 Jack Jones LP, What I Did For Love, and Evans was somewhere in Christchurch. He had Madame Butterfly fluttering away on the Concert Programme. The interview began at 8.30pm and ended sometime after midnight.

Evans has written four novels. The first two disappeared without trace, but Gifted (2010) was a hit, a charming riff on the oddest odd couple in New Zealand letters – Frank Sargeson and Janet Frame. Evans, too, has had a kind of intense relationship with Frame. She was the subject of two critical studies and has occupied a great deal of his thinking. She wasn’t that fond of him, which is discussed in the interview.

He followed Gifted with The Back of His Head, which is also a kind of response to Frame. He has also written popular plays, and critical works, including the very strange Penguin History of New Zealand Literature. He taught English at Canterbury University for over 40 years, and had only officially hung up his – hat? what do lecturers hang up when they retire? – the day before our interview. He has a particular way with dashes and hyphens, and is fond of Capitalising Things; these tics were kept intact.

Patrick, congratulations on your nomination at the Ockham national book awards. But first let us discuss greed. First prize for fiction is $50,000. How savagely would you like to get your hands on that loot?

Without principle or remorse. It’s an extraordinary investment in the arts, and although I am ethereal, unworldly and faunlike I would be able to use the money.

One of the other finalists is the venerable Patricia Grace. You were silly enough to write this of her at the Spinoff last year: “Which of our more recent writers might we think of as worthy of that phone call from Stockholm [for the Nobel Prize]? My candidate is Patricia Grace.” So if the Ockham judges have read that, they’ll say, “Yes, quite right. Fuck Evans. Let’s give this award to Patricia.”

If Patricia were to be the One it would be bottler for all the reasons I’ve indicated, though I’m not saying I wouldn’t sulk and demand a recount if I miss out.

I’ve recently re-read a review of the bone people in a 1985 (UK) Listener and been reminded of the gulf between Them and Us that makes it so hard for some of them to Get It when reading beyond their crumbling shores. We “get” them, but they don’t always “get” us: so much in this is invisible at the Centre of Empah – as it was to some readers here, too, of course. Understanding “the postcolonial” is a crucial need for understanding where our writing, in certain hands, is going – and where it’s been coming from. So the prizes need to come from within till we do. Onward and upward.

I’m talking myself out of the prize here, I see.

Yes, you’re doing a splendid and considered job of that. Can I just ask a little about who you are? You were born in Dehra Dun, India, where your father was an officer in The 2nd Ghurkha Rifles. I doubt it was leisurely growing up as the son of a Ghurkha.

I come from a very conservative background, very much the Raj and so on even though I was here – on Auckland’s North Shore – before I was 5. Ever since then in Christchurch, somehow, attractive to my parents because supposedly the most English of NZ cities – I suppose it was, but never quite right for them, I think.

India – British India – has a mystic hold on its English exiles, and my father especially never left, never stopped being a retired army major talking about tigers to bewildered Kiwi neighbours who had asked him how he was.

I have no reliable memories of anything before very intense recollections of the setting sun glittering on Auckland harbour Curnowishly and my first sense that we’d stopped rushing around and had arrived Somewhere. Negotiating extremely English parents and accents in the fallen world of Papanui, Christchurch and later the paradise of Mt Pleasant on the Port Hills was my childhood and longer. My father was incomprehensible to most Kiwis and tended to end up telling them to open their mouths when they spoke; he described NZ as a nation of ventriloquists.

My mother spent some of her retirement harassing shopkeepers in the retirement suburb of Redcliffs about the spelling on their signs and (especially) their speculative use of the apostrophe. She is the one who encouraged me to write and also prevented me from writing, of course.

This paradise of Mt Pleasant interests me, because in an interview with Margo White in the Listener you gave a litany of the townspeople, who apparently included “an aggressive nudist, a transvestite, a peeping tom, a pederastic scoutmaster, an inventor, an old hermit who had returned from the Great War with shell shock, and a number of bee-keepers”.

And there was young Patrick Evans and his twin brother, who I note you’ve referred to in interviews as a brother and neglected to say twin. If just about everyone there was some kind of outsider, or eccentric, were you, too?

Yes, what you quote does provide the basis of a good counter-description, doesn’t it? A paradise with plenty of snakes, perhaps, including one which the owner just wouldn’t tuck in.

It was nature not the humans in it that were the paradise, that’s the thing: a means of getting away from humans, perhaps. Most of the kids at the local school were decent jokers and some of them were even sheilahs, as we used to call them, small snooty mysterious non-boys obsessed with ballet. My ten-minutes-older brother acclimatised to NZness very rapidly; I did not. It took me decades to feel as if I belonged here, and reading and trying to understand NZLit was part of that. Teaching it, and writing The Long Forgetting, a study of cultural forgetting that was immediately forgotten, were important parts of my acclimatisation.

Eccentric? Probably, in the context of the time – unsporty, unadolescent, fed on a diet of Billy Bunter books and Pommy kids’ magazines, caught in an early postcolonial stew of English public school fantasies and mid-century utopianism (Jet Morgan, Journey Into Space – the Poms first to land on the moon, as in everything). Linwood High School, a recently-built working-class monstrosity built mainly in asbestos and full of Normal Young New Zealanders and teachers who coiled their canes up the sleeves of their academic gowns, was a bracing reality check. There, I perfected my Kiwi accent and learned the use of irony, so important when writing stuff.

Irony, you say! That’s excellent, because I wanted to ask you about your sense of humour, which I think is something that has made you such a maverick. Literature academics aren’t supposed to be funny. They’re usually called Lawrence or Lydia and are very reasonable and cautious.

Now we’ve not met but my Emily has very fond memories of you when she was growing up in Christchurch, because her father Peter Simpson and you were colleagues, and friends, at the English Department at Canterbury. And so she tells me of a Patrick Evans with a very sexy, very glamorous wife, a home in Clifton Hill in Sumner, and two sons, and that you were always very, very funny.

This sense of humour of yours – it’s interesting, because it’s kind of been subversive, in a way. I’m thinking for instance of your 1990 book, The Penguin History of NZ Literature, which is my favourite literary study of local writing, not least because it’s so entertaining and provocative and funny. It’s often at the expense of poor old Curnow – he’s variously and vividly described as “a crabby teacher rapping us over the knuckles,” and “a bouncer at the doorway to NZ poetry”.

I interviewed him once. I went to his house. The door creaked open, and there he was, God. And your Penguin came up, and he said, “What a mad little book that is! It is, you know. It’s dotty.” In fact you greatly admire his work, his achievement. Your portraits of him in the book are too complex and thoughtful to be described assassinations but you do, sometimes, make him look such a fool. Is there something in you – a sense of humour, a devilry – which you can’t resist?

There’s a point in every small kid’s life – isn’t there? – when s/he suddenly understands how to handle Them. When I was 14 I remember saying something that made some menacing cretin or other laugh. “You’re not such a bad joker,” he said to me, and in later life went off to manage some big wool-broking biidniss somewhere.

Victims throughout history have done something like that, and it’s no great insight. I remember a line in Thomas Carlyle about watching the House of Lords or something like that, and saying something like, “Look at the little man, in his wee coatis.”

It’s hard not to think like that once Serious People have begun to exclude you, and I have always got into trouble for sabotage and Unsolicited Criticism as a result – I got booted out of Teachers’ College for a Bolshie attitude but also for gumming up the cisterns in the dunnies with broken glass – kid stuff like that. TC seemed to me so full of bullshitters being taken seriously and – crime of crimes – also taking themselves seriously.

Above: Evans’s first novel, Being Eaten Alive (1977): “I tried to write a novel that read like a cartoon strip.” Jacket courtesy of Karen Craig, Auckland Central Library.

Of course NZLit being so insecure about its tininess took itself so seriously it screamed out for satire. My first novel Being Eaten Alive was written to make people laugh, and to take itself as unseriously as possible – I tried to write a novel that read like a cartoon strip. Well, that was tucked under the carpet pretty quickly. Then I tried Serious with my second novel, and no one took any notice of that, either – which surprised me as it had some fairly grim moments. I remember giving a spoof paper at some kulchural festival here in CH and arguing that being called Maurice was the key to success in NZ Lit, and announcing that from then I was Maurice Evans. A shame that Maurice Shadbolt was in the back row, where his mounting anger became evident as I raved on.

For a long time I turned away from prose to get away from this sort of response and wrote plays – theatre people are different, somehow – all of which turned out to be comedies. Making large groups of people laugh is such fun, and here was a way to do it – a play about an English department meeting that introduced rules and then couldn’t work out how to bring the meeting to an end, a play about two blokes trying to give up smoking – just that, nothing else, the two of them like two scorpions in a bottle as they prowled the stage tearing each other apart; then a play about a dinner party where the guests had to pretend the dinner, and my favourite, a play about a men’s group which actually attracted groups of men from men’s groups who seemed to think the actors on the stage were in a real men’s group. The Gifted play was perforce the first somewhat serious play I wrote.

Ah, Peter Simpson and NZLit at Canterbury. He arrived at UC from exile in Revolutionary Canada (Atwood, Trudeau I, etc.) and grabbed us all by the scruff of the neck and dragged us into the second half of the twentieth century, for a start. He picked up Winston Rhodes’s mantle, or whatever, and re-established the teaching of NZLit at UC against the forces of Darkness. Before his arrival I was stuffing around with American literature, trying to be different, and flirting with Janet Frame stuff. After his arrival I was learning about local writing as fast as I could go, trying to keep up. A memorable, passionate lecturer, who performed haka to demonstrate the effect of sound, rhythm and emotion in poetry. Those were the days! – huge, baying classes, hungering for laughter; nowadays, declining Income and increasing Outputs.

“Flirting with Janet Frame stuff” – but you never stopped flirting with her, did you? The Back of His Head is the third volume of a trilogy written in response to your career-long reading of Frame, “who has done most among New Zealand writers,” you said to someone or other, who may or may not have been called Maurice, “to shape my thoughts about the world.”

The first book in the trilogy was Gifted, which was about her time knocking around with the unbearable Sargeson; the second one you haven’t written, but I understand your plan is to set it in Ibiza, where Frame lived for a time after her 10 years or so in madhouses. Will you write it, do you think? You know – how’s your health?

I’ve written 120,000 words of the second novel of the trilogy (as it ought to be thought of) so far and climbed up to the top of Sugarloaf on the Port Hills above my house last Christmas Day, so am optimistic re finishing it. I’d love to write a university novel, of course, and there are projects after that. I retired 100% from UC yesterday after 46 years of teaching, so might be freer to write, though I’m struck by the continuing press of Urgent Trivia.

I recently underwent Belsenish experiences in hospital to find that I am suffering from something called Symptoms. No causes, just effects. A relief in one sense, but a very writerly condition because in effect it’s all just words, which are treated with other words, always Latin, which sometimes have side-effects, also words. I think I am becoming a sentence.

Ah, Janet. Someone – no, it was Italo Calvino – said a classic is a book that never finishes telling you what it has to say. All of JF is like that for me – I’m impressed how she attracts the best students I’ve had. The best of these I’ve ever had is currently at Oxford U writing a D. Phil. on her, and revealing things completely new; this has been a common experience for me from those I teach.

This third-novel-which-is-a-second-novel of mine follows a Janet-like figure to Ibiza, yes, but (cf. the ending of Owls Do Cry), “she had another name”: this is not “Janet”, and the book is a riff on some of the things that happened to her rather than an attempt to “bring her back to life” as in Gifted.

One of the distinctive things about her, for me, is her capacity, it seems, to find cultural and historical fault lines and go there – places you wouldn’t expect to find her. Baltimore, for example, the Afro-American quarter, where she said she felt “close to the human condition”. Also Britain at the time of the Aldermaston marches at the height of the Cold War, something that marks her early fiction; before that she meets a concentration camp survivor in one of the psychiatric institutions she was in, and that figures in Faces in the Water. She has an almost naive, innocent feel for the Ground Zero of mid-to-late twentieth century history.

Researching this new novel I am struck by how much was going on in and around Ibiza when she was there. It was long an artists’ and intellectuals’ refuge (Benjamin began a detective novel there in the early 1930s, about a man who hides a lot of money in a book in his library and then forgets which book it is); and then there was the Spanish Guerra, in which the leftist government forces savagely attacked the Francoites on the island(s) and were then bombed by the Italians, who were Helping Out. The landowners in the centre of the islands of the Balearics remained Francoites, the folk on the perimeter tended the other way; the fishermen e.g. were always communists. The local version of the language of Catalonia was banned by Franco, and Sevillean Spanish was normalised instead.

Given all this, I am surprised Janet didn’t do more with the languages and the theme of translation, which is pure Frame, I would have thought, and I’m surprised too that she says so little about the theme of cultural forgetting which is so central to the Franco era and being confronted still by younger Spanish generations who are literally digging up their grandparents.

Well, all this is waiting there for someone to write about – she left the ball over the pocket, as we retired pool-sharks put it – and maybe it’ll be me. I think I’m starting to see what it is about, what I’m writing, and where it’s taking me, and some days I am very excited about it. And maybe, after all, it won’t come off.

A title would be a help; I made a list of 25 possibilities. The weirdest novel title I’ve read is John Hopkins’s Tangier Buzzless Flies, in which the eponymous insects appear twice, I think, to no particular purpose. A title like that would appeal. Suggestions welcome.

Above: Kerry Fox as Janet Frame in An Angel at my Table, possibly reading Patrick Evans’s biography.

We have to talk about Janet. Again, like Curnow, you approached Frame’s work with a kind of awe; again, like Curnow, your admiration only made her hopping mad.

And now of course you have the wrath of her niece and literary executor Pamela Gordon. She calls you “the enemy”. It’s in a piece which is online and which I hesitate to describe as shrill, but oh dear I guess I just have. She calls CK Stead “the enemy” as well, and Kate de Goldi and Emily Perkins, those two least offensive New Zealand writers, are also given the strap. But it’s you who angers and upsets her the most.

I kind of doubt her reaction keeps you awake at nights. But what about Frame? Were you shaken by her displeasure? There was an early biography of her which you wrote, long before Michael King’s book, which frankly I thought was quite dull or certainly loyal. Neither of those two qualities seemed evident in your study.

You talked later about how you were, metaphorically, rooting around “the shrubbery under the bedroom windows”; and you found that she “sported a family that was the stuff of small-town gossip…a mother who couldn’t cope, a sister who used to dress strangely”.

The book was published and she was not best pleased. She wrote to you. You said to Kate de Goldi onstage once, “It was the angriest letter I’d ever received from someone I wasn’t in a relationship with.” I believe she referred to you as “one of the Porlock people”. Would you care to expand?

The “Porlock people” reference is to the story of Samuel Taylor Coleridge writing his poem “Kubla Khan” while absorbing great clouds of opium to help him along and being interrupted by “a person from Porlock”: and there went the poem, right out the door: it is famously unfinished. No idea who the gripper from the next village was – there’s a story to be written from his/her point-of-view: “Wanted to borrow a cup of sugar so I went to the next village and knocked on this door, see- ”.

I’ve always thought of Baxter’s death as a Porlock moment in reverse: there’s a play in this – a Kiwi couple tidying up after the fish fingers and Watties frozen peas and discussing when Close to Home is on – and in bursts New Zealand’s greatest poet in the middle of a terminal coronary, who then dies lengthily and noisily on their sofa.

The Janet-Porlock story is emblematic of all the demands on the artist that conspire to banish her muse, I suppose, and mentioned in Janet’s letter to me was a pretty strong rebuke; but no, I didn’t feel chastened by it or shocked, just curious. I really did and do think that if you step into the public arena by publishing a book, you have to expect nosey ill-informed people at your door and on your phone etc. wasting your bloody time – it happens to me and I of course am but a poor shrivelled worm compared with JF. Apparently she got a lot of requests for money – from the same wads of cash the IRD boneheadedly supposed were hidden under her bed, I guess.

All the same, unauthorised biographies are no big deal in more sophisticated literary cultures than our own; they’re just – well, biographies that haven’t been authorised. And I said nothing negative about her as a writer or person in Janet Frame, not that I remember, and sometimes have wondered what she expected literary critics would do once she began writing, especially writing so significantly. We have feasted on her, true, but then that’s what we do; so many other writers I’ve met have dropped hints like crowbars when the question of someone writing about them comes up – “Pick me! Pick me!” – but not Janet. She must have been so torn, of course, between public recognition (she accepted certain awards offered her) and privacy.

You have to remember that in an early autobiographical piece, I think in the TLS but maybe elsewhere, she drew attention to a violent, unhappy and even murderous family background, parts of which she seems to fictionalise herself here and there in her writing. But the “Porlock people” thing was a nice touch, I always think, so literary and eloquent of so much more. I’d love to have met her, but there was no chance; and then there was Michael.

The question of the Artist v. the Great Unwashed always seems more pointed here in Zed than elsewhere; I recall a neighbour asking me if I was a baker (lights on all night, asleep in the morning and so on). There are moments when I think what the hell am I doing, trying to write? and I’m sure I’m Not Alone in this.

I admire writers who are firmly Here in what they write and comfortable in it: Damien Wilkins is one (The Miserables, eg) as is Carl Nixon, who has a wonderful play at the Court I saw a couple of days ago called Matthew Mark Luke and Joanne which EVERYONE SHOULD GO AND SEE. But on the other hand Carl Shuker sets so much of his fiction outside Zed (Japan, Lebanon, England), and now THERE’s a writer to admire.

I also like the stories about Frame hanging out in Mitre Ten for the conversations she overheard there, and (I think this is right) riding on buses for the same reason. A Dunedin friend of mine used to spot her enjoying the Pensioners’ Meat & Two Veg on Sunday lunchtimes at the local pub later in her life, when (They Say They Say) she was under the illusion that no one knew who she was when in fact everyone did but for her sake played along with the idea that she was just a little old lady. I love her modesty, and the thought that someone who really was a little old auntie at one level could have written some of the really, really wild stuff she came up with – gravity stars that suck language out of people’s mouths, two men making love on a sofa and giving (figurative) birth to a buffalo, the Carpathians turning up in the Wairarapa, dead characters who are alive and live characters who are dead, and the bloke who bleaches his bath and is bleached from the text. The antidote to Maurice Shadbolt.

Last year I had builders in my house doing my EQC repairs (a very Christchurch phenomenon). All day I’d hide in my study and try to create Art as the banging and sawing went on just the other side of the door; but I came out twice a day into Life for smoko, when they’d try to find out what I was up to in there and what went on at university. I wrote down one of these conversations as soon as it had happened:

“What’s goin’ on out at the varsity, then – ?”

“Oh – not much, pretty boring really.”

“Naah, but them sheilahs’d be hangin’ round, ay – ?”

“Not really, not round me.”

“Aw, come on, you’d be getting’ a bit, wouldn’t yer? They’d be cryin’ out for it – ?”

“Ah – well, not near me they aren’t.”

“See ’em round town, just the one thing they’re thinkin’, you can tell – that what you’re teachin’ ’em, ay, teachin’ ’em about rootin’ -?”

“Not really, it’s more about getting them to read stuff and then write about it.”

“Yeah, but what is it you getting’ ’em to read? Ay? Must be turnin’ ’em on, they hangin’ round lookin’ for it?”

“Not really, I’m just teaching them English.”

“That’s what you’re teaching’ ’em – ?”

“Yeah.”

“Shit.That’s woman’s work, innit?”

“Women’s work?”

“Yeah. Innit? Women’s work – ?”

“Yeah. I suppose it is in a way. I suppose it is women’s work.”

“Too much of it around.”

“What?”

“Women. Too much of it around, that’s the problem I reckon. And no one’s doin’ anything about it. No one’s doin’ anything about it.”

I’d mentioned we’ve not before but we do have history. We have form. In 2002, as books editor at the Listener, I ran a piece by you which caused a terrible fuss and wrath poured upon your head while I walked off scot-free. You’d written something Very Serious about NZLit in an academic journal but it contained certain provocative comments about the creative writing programme at Victoria, so I abridged the essay and made hay of the certain provocative comments.

You described the course as “obviously a conveyor belt that, once one is aboard, offers a high-speed ride to exactly where any young writer would want to go” – that is, it inexorably led the writer, like an attractive piece of luggage, to publication in Sport and then by Victoria University Press. The thing that was most upsetting was your reference to these students being “preferably female and attractive”.

Now Bill Manhire is of course the least quarrelsome or confrontational of men and wouldn’t know a feud from a spat, but he later told the magazine, “I think it was his fantasy that the Victoria course consisted of me choosing beautiful young women who I had in my Svengali-like spell for a year or so … before moving on to the next bunch of beautiful young women. Bizarre. I think it was, I don’t know, maybe what Patrick wished was happening in his life.”

In that same story, you said my abridging had “distorted” your essay by putting more focus on Manhire than you intended. Fair call. That’s accurate.

But the key to your essay, I think, is when you write, “It is obvious that if you happen to be in your early twenties and keen to become a writer in New Zealand, what is represented by Manhire and his course …stands before you as Murray Edmond once described Baxter standing before the writers of his own generation when they started out: as things that, one way or another, need to be confronted.”

I liked that the programme was being confronted, because it’s an orthodoxy, isn’t it? Obviously it produces a wide variety of writing and all that. But it’s all very Approved Wellington Lit kind of thing and I think it can stand a bit of confrontation. What are your thoughts now on that confrontation?

No comment.

One final question, although once again it may take me a while to get to it.

I was quizzing you like some kind of Nazi before, about suspecting you might be in possession of a sense of humour – vas is zis “humour”, mein Herr? But Emily was saying that although you were a very entertaining lecturer and always good for some LOLs, you also took it really seriously and it was obvious your lectures were the result of a lot of hard thinking.

There’s something else going on in your critical work I think, and that’s a generosity of spirit. It’s there in that comment you made about Patricia Grace deserving a phone call from Stockholm, and it’s there at greater length and depth throughout the Penguin. One of the outstanding features of that history is your insistence on noting the presence and influence of women writers. The literary orthodoxy was for a long time full of sexist old shits; you write of Saregson, on Robin Hyde, how in a memoir or something, he “turns her into an obsessive figure limping around his bach declaiming her latest work with a string of sausages dangling from her hand.”

But you recognised Hyde’s strange genius, and the impact and achievement of many other women writers – and Maori, too. I asked you recently which books you would nominate as among the best ever books of New Zealand non-fiction, and here’s just the tail-end of that list:

Tikao, Teone Taare, and Herries Beattie. Tikao Talks. Ka Taoka O Te Ao Kohatu. Treasures From the Ancient World of the Maori. Auckland, Penguin, 1990.

Underhill, Bridget. Kōmako: A Bibliography of Māori Writing in English. Digital Humanities Department, University of Canterbury, 2015.

Walker, Ranginui. Nga Tau Tohetohe. Years of Anger. Auckland, Penguin, 1987.

Walker, Ranginui. Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou/Struggle Without End. Auckland, Penguin Books, 1990.

Walker, Ranginui. Ngā Pepa a Ranginui. The Walker Papers. Auckland, AUP, 1996.

All of which is also to say – because I don’t want my other questions to stupidly and narrowly cast you as some hee-hawing jester or ancient enfant terrible – that you’re very serious about writing and literature, wholly engaged.

There ought to be a question at the end of this monologue so as to bring you into the conversation, and in fact end it. How about this: do you miss the active immersion in NZ writing? You gave your final lecture last year, on David Ballantyne’s singularly brilliant Sydney Bridge Upside Down. What goes on in the mind of a retired English lecturer? Is there a kind of intellectual loneliness, a void? A lecturer without students – is it a game of only one half, or something?

Yes, I’ve always taken it seriously – I’ve been a vocational teacher – but tried not to take myself too seriously; golden rule. Sometimes it works.

A vocational teacher is someone who understands the meaning of the phrase “the romance of the classroom”. It has never left me, and I had to make myself retire after coming to the end of a three-year contract that extended the normal term of my career. Now that was a real wrench, the last lecture, though the students were very good to me and staff came along and there was cake. There’ll be nothing to replace the classroom for me, though, and actually pulling the plug all the way out as I’ve done now is a strange feeling.

The writing fills the void, to a large extent, though I do like young people and there are fewer of them in my life now. I still have a desk there and will be able to keep up with colleagues so there’ll be no intellectual loneliness, I don’t think; they’ve been extraordinarily generous to me over the years. As long as I don’t start drifting in to afternoon tea wearing walk shorts I’ll be okay.

You’re kind about the things you say. The thing I’ve learned is that it’s not a competition, and also (Coriolanus) that there’s a World Elsewhere. As to my interest in Janet, Hyde, etc: I have always felt close to women when I write, whatever it is I’ve written; in sympathy, I mean. I “naturally” tend to write women characters, a sort of literary transvestism I feel comfortable with. This is partly I think because of never having been an alpha male and loathing the type, by and large, and having some small sense as a consequence of what women have to put up with.

But also it’s just curiosity, which grows greater as a man ages (I think) and falls off the back of CS Lewis’s horse – a simple curiosity about what it’s like to be a woman, the body difference but also in a still-very-heavily-male-advantaged country/world. To some extent there’s a cultural silence there, too, even after second-wave feminism and the wrenches of the 1980s; but even more so with Maori cultural history, where (as I growingly realised while researching The Long Forgetting) there is a huge, willed blank. Anyone who wonders why I am presently trying to write about a culture that has decided to forget itself (Spain) should find their answer in figurative thinking. I wonder if anyone will pick up on that if the book eventually emerges?

There’s so much truly new and exciting stuff (I’m thinking of that booklist of mine you quote) in Maori history and ethnology – I became so obsessed with it that one of my colleagues formally asked me to stop talking to him about the loss of the Pink and White terraces and the effect this had on local Maori social economies. I could clear the tearoom in those days, nil perspirandum.

Yes, I think about writing all the time, in amongst the other sludge that occurs in the preterite. All. The Time. Maybe if I got a caged bird and taught it tricks – ?

The Back of his Head (Victoria University Press, $30) by Patrick Evans is available at Unity Books.