Sam Brooks reviews James Courage Diaries, edited by Chris Brickell, and A Queer Existence, by Mark Beehre.

“My very writing, for what it is worth, is a cowardly escape from myself – from the hostility of one part of my mind to the others. Which produces in me a constant warfare, which, it exhausts me to contemplate, I feel inside me.”

That comes from one of James Courage’s diaries. It’s a remarkably salient observation on the internal struggles of a writer, an observation you can imagine someone agonising over before eventually writing it down, maybe after a few gins. More importantly, maybe, is that the reader can also sense the fight within it: it’s written with the clear intention that nobody other than the author will ever read it – but also with that hope specific to writers, the hope that in some far-flung future, someone might read it and have a little bit more light shone upon the world they live in.

You probably haven’t heard of James Courage. Before cracking open his diaries, edited by Chris Brickell, I hadn’t either. The author, born in Christchurch in 1903, was one of our first male authors to engage with his homosexuality in his writing (although, notably, he didn’t like the term “queer”, and used it to disparage other “members of his fraternity”). He moved to London in his 20s, published eight novels, and wrote a then groundbreaking, now unheard-of play that detailed relationships between boys at boarding school. His 1959 novel, A Way of Love, is thought to be the first gay novel written and published by a New Zealander.

Upon his death in 1963, Courage’s sister sold his diaries, along with other personal papers, to Dunedin’s Hocken library, but placed an embargo on them for 30 years. This new collection publishes his diaries kept from 1920 until his death, along with a quick introduction and foreword giving a context that I imagine will be necessary for most readers. The entries are edited for grammar and readability.

The picture that Courage paints of himself, with some delicate and helpful framing from Brickell, is a tricky one. The diaries are remarkably forthright in some cases – Courage does not hold back when talking about the other people in his life, whether it’s his family, his fellow writers, or the numerous affairs that he has throughout the years – and less so in others. There is surprisingly little written about A Way of Love, which made waves at the time, although you might ascribe that to other people writing about it enough on his behalf.

Perhaps the most illuminating part of these diaries, reading as a queer writer from a very different time and place, is that Courage doesn’t appear to have lived a half-life. It can be easy for modern audiences to assume that queer people – apologies to Courage for the label, but I presume he’ll forgive me – who lived before us, with vast restrictions on their freedom of expression, had to also live in ways that were less full or rich than ours.

For Courage, there were pragmatic constraints – he was impoverished, as writers ahead of their time tend to be, and he lived through World War 2. But the life that he describes doesn’t sound empty at all. The love he had for sailor Frank, seaman Chris and unionist Steve feels as potent as any modern relationship I might read about in, say, The Cut’s relationship diaries.

And my god, the man was witty. On his own approach to writing: “Same old fear of iconoclasm or just finicky laziness.” On someone he doesn’t like at one of the many parties he feels compelled to attend: “A completely fictitious person.” On love: “Love is ecstatic sharing, stretching forth, giving, of self.”

As an introduction to Courage the author, these diaries are understandably lacking. Such is the nature of the form. If diaries aren’t the best introduction to a person, they’re an even weaker first serve for an author. An author’s best, and most illuminating, work is not in their first draft; their work is meant to be honed, refined and sharpened. A diary is the opposite of that; it’s all the words a person has in the situation, put onto the page so they don’t have to carry the full weight of them anymore.

However, as an introduction to Courage the person, and where that person sits in the world, Brickell’s collection, or at least his framing, is an important one. It’s an understandably niche pitch down a narrow field – I’m not sure how many people are aware of Courage, and therefore likely to check out the diaries of an author they might not have heard of – but as another queer story in a depressingly slight bookshelf of them, it’s a welcome one.

Reading Courage’s diaries was a strange experience for me, as both a queer reader and a queer writer. As a reader, I was moved, not uncomfortably, whenever Courage expressed something that I’d felt, but in better words, or with much more precision.

As a writer, I kept on running up against my own questions for Courage. Was he being honest to himself? Was he the best chronicler of his own story? Is this the way that he would have wanted to communicate his story to the world, with the relatively blunt instrument of inward-facing autobiography rather than the refined elegance of fiction? Brickell’s framing can only do so much, and for a lot of the collection’s duration, it felt like I was eavesdropping on somebody talking to themselves in the other room, prepping for the big speech that an audience actually came to hear.

It’s hard to check these reactions, and impulses. It is a cruel irony that the people who can be harshest about stories told by authors from marginalised communities are the very people that those authors intend to speak to, and speak for.

People from marginalised communities are used to having to interpret themselves into text, rather than simply see themselves in it. The mainstream gets to walk into these texts through the front door, whereas we have to jimmy a lock or climb down a chimney to find our way in. If you’re not seeing queer relationships in the books you’re reading, then of course you’ll take the affection between Frodo and Sam as confirmation of a romantic relationship. If all you have is straw, you’ll end up spinning some pretty dubious gold.

However, there’s been a crucial shift in the conversation between authors, across the spectrum from mainstream to marginalised, and their audiences. Marginalised communities want to see themselves in stories, in fact, everybody does. The issue, though? The authors have to get it right.

The impulse to want to see yourself reflected in stories is an understandable one. If you spend your entire life having to imagine your way into a work, just to be able to relate to it, it can be frustrating to have art that purports to be for and about you completely fail.

“Right” is an impossible target to hit. Communities are not monoliths. Someone else’s lived experience is another person’s fantasy. The only thing an author can do is be honest to their story, their characters, and themselves, and hope the audience comes along for the ride.

If you look into a story, any story, and expect to see yourself reflected back exactly as you are, then you’re looking for the wrong thing. There’s a pane of glass in your bathroom that can do that for you, my friend. Stories aren’t mirrors, they’re windows.

And the more windows the better.

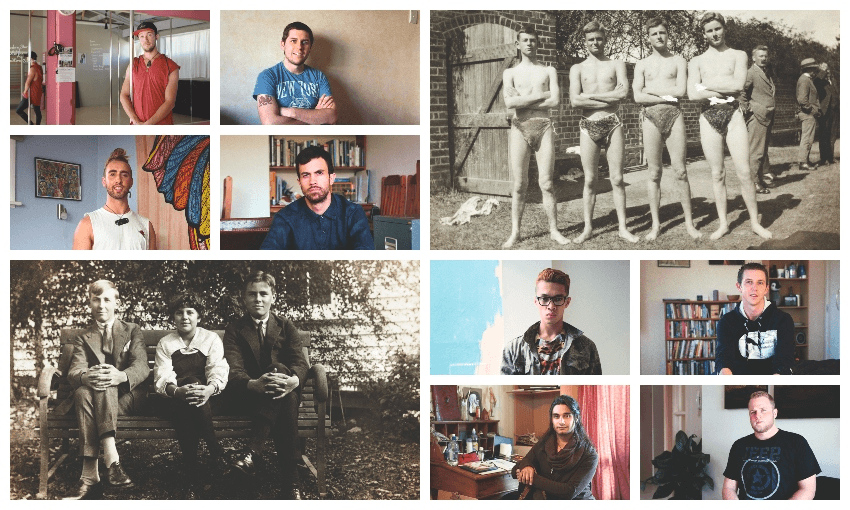

A Queer Existence (subtitle: “the lives of young gay men in Aotearoa New Zealand”) is a collection of 27 first-person narratives from gay men born in the few years after the passing of the Homosexual Law Reform Act in 1986. It’s by photographer Mark Beehre, and follows his book Men Alone – Men Together, a collection of 14 couples, 14 single men and one trio, and continues his work of filling in the gaps of the lives of queer men in Aotearoa.

The book began as part of Beehre’s MFA at Elam School of Fine Arts in 2013, where he photographed and interviewed the first group of participants. From there, he spent eight years gathering up diverse participants and their stories, usually through word of mouth.

Each man is accompanied by a photo, taken by Beehre, and an interview. The methodology here is robust to a fault: transcripts were returned to the participants to review, then edited and amended for corrections and deletions. These edited transcripts were then used to create a first-person narrative which was arranged to “ensure coherence and fluency”. Beehre has tried to preserve the vocabulary and individual voice of each speaker.

There’s no faulting Beehre for the breadth of experience presented in A Queer Existence. Indeed, the only limits here are chronology – between 1968 and “the early 90s” – and location (Aotearoa). He’s also structured the book very carefully. Experiences we might be familiar with are at the start: the white, the cis, the urban. Towards the end come more varied stories – Māori, Filipino Sāmoan and Christian stories – as well as lifestyles that exist far outside even the publicised homonormative. There are some clever moments where certain locations and groups that pop up in one story echo in another (Toi Whakaari, Urge, UniQ), reminding us that if Aotearoa is small, then the queer community in Aotearoa is even smaller.

If there’s one flaw to A Queer Existence, it’s that Beehre’s presentation of the men within it has the odd effect of flattening out each individual story. Some of this is simply the nature of the format: 27 stories told over 350-odd pages in a coffee table book format doesn’t make for the easiest read. But it’s also about how Beehre’s chosen to tell it. He explains that he tried to preserve the voice of each speaker, but many of the men end up sounding more similar than I imagine they would in real life. Take, for example, the two opening paragraphs of Jacob Dench and Stephen Jackson, respectively:

“I’m a person seeking an interesting life and not wanting to conform. I love travelling. I love learning languages. I studied to be an architect and I’m passionate about that, but I’m not sure if it’s going to be the main driver in my life anymore. To a high level, I’m also driven by love and relationships.”

“Having grown up in a Christian-oriented world and heavily involved in the church, I was in denial about my sexuality. I definitely had plenty of ideas and did what I assume every 16-year-old guy does when they have the internet. But I tried to see it as a phase, and when I realised it wasn’t I kept it quiet. I was part of the church youth group, and as I grew older took on a slight leadership role, playing piano, and singing a bit, in the band that led worship time.”

I’ll put it bluntly: they feel edited. Which is because they are. But the reader in me wants to meet these guys and hear their stories in their own words, and the writer in me wants to hear what their voices sound like edited not for reader clarity, but so that the clarity of their lived experience comes through – be it messy, joyous, dramatic or dull, because gay people have the glorious privilege of being boring too, and that’s OK.

In his introduction, Beehre rightly says, “There is no such thing as a ‘typical gay life’ and a different author with a different set of connections would have identified a very different set of participants.”

Beehre’s right. If you put this project in my hands, I’d probably come up with 27 completely different men and tell their stories in my own way. It’s Beehre’s book, and it does the job that it sets out to do: it documents the lives of these 27 men, and their relationship to their own sexuality. He even notes that, given his own background, “a seemingly high proportion of participants” grew up in strongly Christian families.

But whatever issue I take with Courage’s diaries and Beehre’s book as a writer, I have to swallow. That’s not because they’re immune from critique (although diaries were never written to be critiqued and critiquing a once-in-a-generation document like A Queer Existence seems churlish). It’s because I want more of these. I want more diaries, I want more coffee table books, I want more stories. The solution is not to critique them for what they’re not, but to bring forth more stories that fill in the gaps around them. Fill the bookshelf, don’t burn the few books that are there already.

So as a queer reader, I have to take these stories as they were intended. They’re not meant to cater to me specifically; art is not a tasting menu. They also aren’t meant to reflect my story. Hell, I look at essays I wrote about myself a year ago, and don’t feel like they adequately reflect my story, let alone anybody else’s. But we write not to reflect, but to reveal. We put language to our experience of the world, and hope it helps other people do the same.

That matters so much more for marginalised communities. As authors, we have to put language to our experience so that people aren’t trying to find two coins of meaning to rub together in texts that never thought of them or their experience. As readers, we have to give authors the goodwill of meeting them halfway. Looking past our reflection in the window into what’s actually on the other side.

I had a moment of that during James Courage’s last diary entry. He spoke of his own end with the kind of grace and dark humour that I long to have when facing any sort of great unknown, be it the end of lockdown or well, the end of life:

“At least I think I can see where I’m going, in a blinkered sort of fashion.

“No masochism.”

James Courage Diaries, edited by Chris Brickell (Otago University Press, $45) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.

A Queer Existence: The lives of young gay men in Aotearoa New Zealand, by Mark Beehre (Massey University Press, $45) is likewise available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.