Announcing the winners of the 2019 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young People.

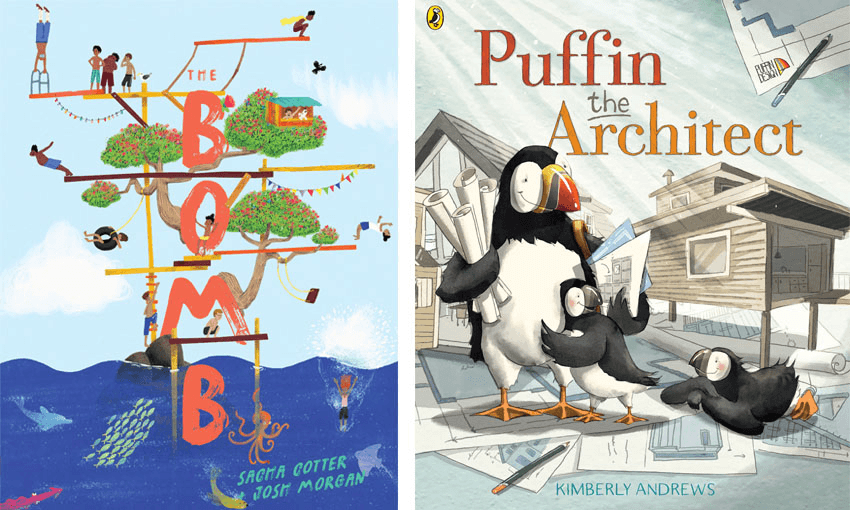

Right now the loveliest people in the country are gathered at Te Papa celebrating 2018’s most brilliant and amazing books for children and young people. The best of the batch, officially, as of just a few minutes ago: The Bomb. Written by Sacha Cotter and illustrated by Josh Morgan, published by Huia, it’s a picture book about a kid learning to drop a sweet bomb (as in the splashy, jump-off-a-bridge kind) and it just won the biggie, the Margaret Mahy Book of the Year. Hell yeah.

Here’s the press-release bit about The Bomb:

The judges were captivated by the spell this book cast. They described it as a summery, waterlogged, quintessentially Kiwi story about a child growing in self-confidence while striving to achieve the perfect “bomb”, supported every step of the way by the reassuring presence of his Nan.

“Joy and humour permeate the story and illustrations of The Bomb, and the reader is rewarded with each encounter – they see a new layer, another detail is revealed, fresh energy bubbles up,” says convenor of judges Crissi Blair. The judges also commended the language, which naturally incorporates te reo Māori, and the illustrations which celebrate our multicultural community.

The win rounded out an action-packed few months for the author and illustrator team of Cotter and Morgan, who have a winning partnership off the page as well, having recently become engaged and welcomed their first child into the world.

Baby arrived in June. We hope he’s sleeping like a sleepy champ, and goes easy on them tomorrow.

For posterity, here’s what The Spinoff wrote about The Bomb when the shortlist was announced:

Layer upon layer of goodness and wonder. Take the inside cover, for example: it’s a child’s scrapbook of treasures, but to an adult’s eye speaks also to the importance of tipuna and links with the land. There are flattened daisies – those tiny ones with the pink tips, that grow in lawns – a feather, a kōwhai flower that a child with a red felt pen has transformed into a mermaid’s dress.

Taped in, too, are old black-and-white snapshots of an elegant, fabulous young woman, and more recent, colour shots of that elegant, fabulous woman, now a Nan, doting on her grandchild. They’re making daisy chains. They’re at the beach. They’re absorbed in each other. They are, of course, the heart of this story, which is ostensibly about the child learning to pull off the perfect manu.

The drawings are intricate: a jetty is wonderfully higgledy-piggledy, perspective is played with, there are physics equations scribbled inside splashes. And listen to the words! Read silently they bop about pleasingly; out loud they’re a delight: “I’m always dreaming of pulling off that perfect bomb. A booming one, a slapping one, a splashing, dripping, soaking one!”

The skins in this book are brown. The landscapes are an if-only green and they teem with tūī and pōhutukawa, kererū and harakeke. It’s Aotearoa as Eden. Lush, gorgeous, laid-back, populated by happy people in baggy boardies dropping sweet bombs.

I think The Bomb should win this category, and I really think it will. Actually, I think it has a shot at the Margaret Mahy Book of the Year.

*

In other news: The Bomb won the picture book category, too, ahead of our next-best picks Puffin the Architect and Things in the Sea are Touching Me.

Puffin did pick up the Russell Clark Award for Illustration for Kimberly Andrews, though. You know when you did graphics at school and there was one kid in the class who constantly busted out the most intricate drawings of fantastic treehouses and igloos and flying fox set-ups? Yeah I bet Kimberly was that kid.

Bren MacDibble hangs onto the Wright Family Foundation Esther Glen Award for Junior Fiction for The Dog Runner – she won the same prize last year for How to Bee, which shares its people-as-pollinators premise with the excellent adults’ novel The History of Bees. It’s climate change havoc again in The Dog Runner: grasses all over the world have died out and two children are desperately fleeing across a barren Australia. “The Road for young kids,” but better, according to our friends at The Sapling.

Whiti Hereaka won the young adult fiction prize for Legacy, a World War I book of “assured writing, cleverly constructed story and pitch-perfect historical rendering”.

The Wright Family Foundation Te Kura Pounamu Award for te reo Māori went to Te Haka a Tānerore, which tells the origin story of the haka. Written by Reina Kahukiwa, illustrated by Robyn Kahukiwa, translated by Kiwa Hammond; judges “praised the way its close connection to identity and heritage was illustrated with exceptional artwork”.

Finally, Art-Tastic, Sarah Pepperle’s deeply informed, deeply non-precious hybrid of activity book and art history primer rightly won best first book and the Elsie Locke Award for Non-Fiction. It’s a stunner: the super-heavy-duty cover looks like a piece of stained glass and every page is crammed with cool facts and slightly mad activities. But the tone is what really elevates it. This book all but bounces off the walls. It’s high as a kite, high and noisy and excited, saying poo a lot then snickering, saying it again a bit louder, needling for a reaction… Basically it’s the book version of a kid stuck inside on a rainy day – which is precisely why we nabbed a few pages of it for you last school holidays.

Congratulations, everyone. And my boy says thanks for the cool awesome books.

The Bomb, by Sacha Cotter and Josh Morgan (Huia Publishers, $23) is available at Unity Books.