Nic Low hops on his bike and heads into the hills, looking for the late Bill Hammond and his bird-people.

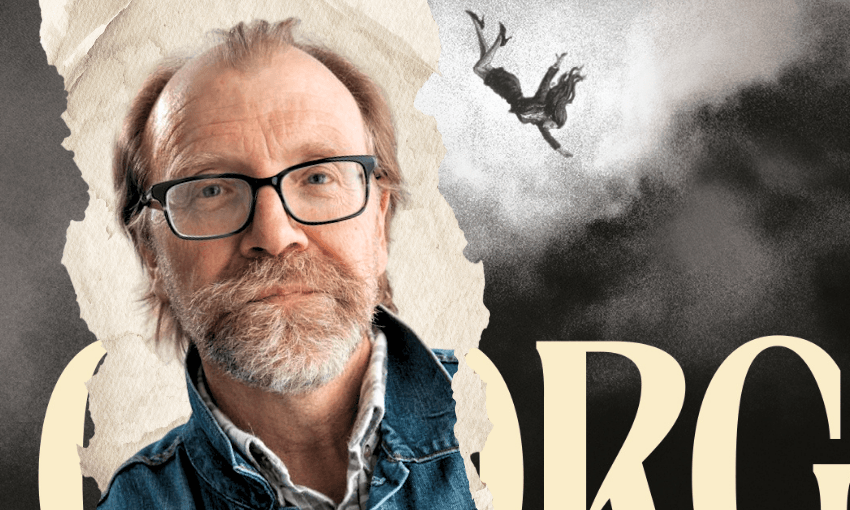

The famously private Christchurch painter Bill Hammond died last summer. Best known for his paintings featuring eerie avian figures, he had started working on a book with the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, Across the Evening Sky. Out now, it’s an enormous, exquisite book and brings together dozens of major paintings with writing from Rachael King, Marlon Williams, Ariana Tikao, Shane Cotton, and others. There’s also a wonderfully frank, rambling interview between Hammond and his friend and fellow artist, Tony de Latour. But the standout is this piece by writer and Word festival director Nic Low.

I go out to Horomaka on my bike in the rain with a ruined knee, looking for Hammond. It’s a headwind from the south. I’m in love with that wind. Along the causeway to Raekura my tyres sing and I suck down lungfuls of sea air: that mudflat stink, that sulphurous rot and the clean brine tang that is, today, and was, 50,000 years ago, the smell of birds.

Black tōrea ride at a lull on the outgoing tide. Karoro tilt overhead. There’s an earthy petrichor scent too, of midsummer rain awakening the ground. I’m joyous at the work of riding and sensing to be done.

The hills are distant, then, abruptly, here. Cut into the volcanic cliffs at their base is the dark mouth of Te Ana a Hineraki. A fence of black spikes palisades the entrance. They used to call this Moa Bone Point Cave. It’s the entrance to Hammond’s mind. The cave mouth’s craggy silhouette frames many of his thoughts.

The chambers within were once layered with shellfish middens and polished tools, beds of ash and oven-stones, pukatea fire-sticks, and deeper again, among the moa femurs cracked open so the marrow could be sucked clean: fragments of a dream of a time when birds ruled.

Today the fence keeps us out, or them in. But if you stand as I stand, fingers laced through the steel bars, and simply stare for long enough – for your eyes to adjust, and the hiss of passing cars to fade, and the salt wind to strip the paint from your house, the skin from your bones – you might envisage a painting on the wall: an enigmatic figure with the head of a bird.

She has a wedged tail and holds her feathered wings outstretched. Smaller birds perch along her arms. Artists have rendered her in charcoal and oils in caves in Fiordland, North Otago and South Canterbury. Paintings of bird-people appear on cave walls right across the Pacific, from Rapa Nui to Muna Island in South Sulawesi. The oldest cave painting ever found – 43,900 years old – shows a humanoid figure with a beak.

I rere mai kā takata manu ki konei mā ruka waka: the bird-people flew here, on a boat, in the care of the Waitaha people, and have taken up residence in our dreams.

Hammond helps keep those dreams alive. His bird-people gaze out across Horomaka waiting for something that has, in all likelihood, already come to pass.

The rain intensifies. I pedal up the road to Moncks Cave: another volcanic mouth glimpsed through a fringe of harakeke and another line of spikes. Around the year 1400 a landslide sealed this cave and the still-life tableau inside. In the 1890s road workers accidentally broke open the time capsule and clambered inside, moving among fishing nets and bird-spear barbs and pāua-shell bowls, breathing 500-year-old air.

No moa bones were found inside, suggesting that, by 1400, the moa were gone.

Seated on a park bench, trying to catch a waft of that air, it seems reasonable to me that the people who lived inside didn’t draw bird-people – they were bird-people.

I ride further south into the wind. I don’t see Hammond in the eroding cliff-lines along the valley inland of Sumner beach. I don’t see Hammond in the teenagers sprawled on benches outside the fish and chip shop. I don’t see him here where the hills demand you be a body, in motion, with no time to stop, or look, or wait.

The hills rise and I ascend, standing and mashing upwards towards Evans Pass. I pray to the gods of lower gears and functioning knees while the wind drops in the lee and I’m encircled by the musculature of the earth, and I still don’t see Hammond’s poise or his watchfulness in any of it—until I reach the top and the land dissolves into sky and cloud, and then, abruptly, here he is.

Up on the pass the world becomes a haze of sea merging into cloud. The land is mere slivers between water and sky, and with height and distance it becomes abstract: a canvas for our myths.

This is the view from Hammond’s caves: Horomaka as smoking volcano, as stands of bush against luminous space. As a place peopled by birds.

I see Hammond in the ink-rain melting the view. I see Hammond in the clouds bleeding to earth as black squalls move across the city below.

Some myths talk about the land before people. Some myths talk about how people were always here.

As a child, I loved Horomaka until someone told me about the dense bush that once covered these hills. After that I only saw the forests of ghosts.

I see Hammond in the axed hills, and the quarry visible from the Evans Pass carpark where I stop to catch my breath. The Lyttelton Port Authority has flayed open the side of the mountain to reveal bands of raw volcanic rock. It is an excavation, an archaeology. They are looking for that entrance to Hammond’s world.

“Reclamation Project”, a sign says, but there’s no indication of what they’re trying to reclaim.

The birds wait and watch. What do they anticipate, or fear? The blasting of rock by the Port Authority? The trees are already gone, and the land is next. Civilisation requires dynamiting the hills and bulldozing them into the sea.

How many birds did this land support? How many does it support now?

The stupefying, deafening dawn chorus.

The deafening dawn chorus.

The dawn chorus.

The dawn.

The

rain has stopped.

Riding west along the contours of the exhausted volcano, the dawn chorus rekindles in fledgling bush in the gullies I speed past. I catch the sweet perfume of life in bloom. There is toetoe and there is harakeke, unkillable and beautiful, with wax-eyes swarming the heavy flowers.

In Māori, wax-eyes are tauhou: newcomer or stranger. They first appeared in Aotearoa in the early 19th century after being blown across the Tasman in a storm. They’re protected as a native species today.

Aotearoa will be predator-free when we manage to kill ourselves off.

Through a smear of glowing cloud, the sun moves as I move, reflecting off the curling taniwha of the estuary. Another storm cell rolls in from the south to strafe the plains. The alps hover at the horizon, glowing white.

One of our oldest ancestral hapū is Te Aitaka a te Puhirere. They were most likely symbolic and mythical ancestors. But once, standing in a cave covered with frescoes of ancient art, I was told an improbable theory about the name.

Aitaka means the progeny of. Puhi is a high-ranking woman. Puhi means adorned with feathers. Rere means to fly. And not so long ago, near Wānaka, a rock climber abseiled down an unfamiliar cliff and found a cave, and in the cave, human bones. He and his climbing partner called the police, who pulled out a skeleton wrapped in a feather cloak.

Years later, a Ngāi Tahu man working on high country tenure review overheard those climbers in a bar, reminiscing about their find. He pricked up his ears.

Kōiwi is skeleton; kōiwi is line of descent. Any bones found in caves around there would be an ancestor of his.

“Where is she now?” he asked.

“You’d have to ask the cops,” came the reply.

The man visited the cave. The police hadn’t been gentle, and had left a fragment of a femur behind. He took it with him and initiated a search. It turned out kōiwi had been sent to the Otago University medical school. “You’re in luck,” a contact at the school said. “We’ve just done a full audit of all human remains. Leave it with me.”

But when the Ngāi Tahu team visited the university, they were told that there was no skeleton fitting the description. Perhaps it’d never arrived.

The meeting was after-hours, and a cleaner was working in the background. She piped up. “There is that skeleton in a box on a shelf in professor so-and-so’s room,” she said. “There are feathers in there, too. Come and have a look.”

There in a dusty box was a pile of bones, a skull, a feather cloak. One femur was missing a piece, and the piece from the cave matched.

She was returned to her resting place along with her cloak, and the cave sealed.

But first, the Ngāi Tahu archaeology team had three days with this puhi. They discovered that she had lived around the year 1400, and had spent her whole life in the inland high country.

But what astonished them most was her kākāpō-feather cloak. The skins had all been pre-stretched, with holes punched along the edges, then expertly stitched to create a single shimmering coat of feathers.

“It came almost to the ground,” the teller of the tale told me, indicating a point half-way down his calf. “It would have followed her every move. And if she’d bobbed down, so the cloak covered her feet, she would have looked exactly like a bird.”

It’s time for me to descend. Riding the summit road – the potholed road, edge crumbling away, the barrier smashed by rockfall, the serrated crags above – I pick up speed.

I fly through the corners now, brakes howling in the wet, grinning, accelerating, leaning the bike, laying off the brakes, using both sides of the road, feeling myself grow weightless over little rises, feeling gravity losing its pull, until there’s a long straight, steeply down, and I’m headed for the corner at the end and I don’t bother to slow.

I take my hands from the bars and raise my arms and soar.

Up here you can feel the wind in your feathers. The whole of Horomaka lies beneath you.

Smoke curls from its crater in a perfect ribbon, and beyond are the alps running down the keel of this canoe that is an island, with the ocean glowing on all sides. Still you climb free of the earth, until you are a weather-pattern, an all-seeing eye, standing there, warm and dry in the gallery, admiring our painted figures in flight.

Bill Hammond: Across the Evening Sky, by Peter Vangioni with Tony de Lautour, Rachael King, Nic Low, Paul Scofield and Ariana Tikao (Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, $69.99) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.