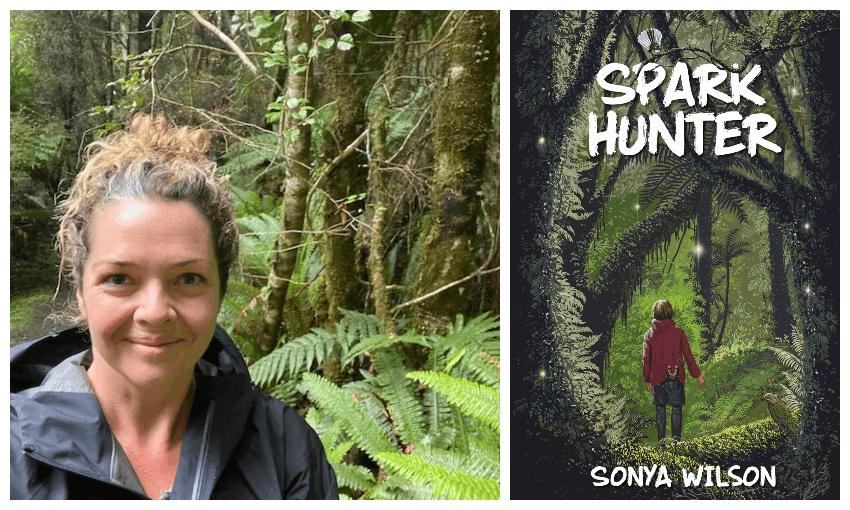

Spark Hunter is a story about fairies in Fiordland, and it’s one of the best YA books we’ve read in years. Here, the author explains that it stems from an obsession she’s had since she was a kid.

My husband nearly wets himself laughing.

“You were such a nerd!” he says.

“No I wasn’t! I was …” I look up, searching for the memory on the ceiling, but there’s only fly spots. “I was … cool. Like, a cool nerd.”

“Were you really?”

“Yes!”

He points to the Duraseal-covered 1B5 exercise book in my hand labelled: SONYA WILSON / RM 8 / 1991 / ROSEDALE INTERMEDIATE and laughs like a bird from the country where he was born: a kookaburra, or a crow.

I had hunted for this old school book of mine amongst the vast landscape of decommissioned vehicles and family flotsam in my parents’ shed because I thought it might help with the editing of my novel. Spark Hunter features a 12 year-old girl from Invercargill who goes to school camp in Fiordland’s Deep Cove. I was once a 12 year-old girl from Invercargill who went to school camp in Fiordland’s Deep Cove, and I was — I had thought — much like my novel’s protagonist: quite fond of Fiordland, and also capable and rugged and cool. But my husband’s face as he turns the pages of my school camp-era exercise book suggests otherwise. Seeing this work in the cold hard light of 2021, alarmingly, I think he might be right.

In 1991, the Deep Cove School Hostel at Doubtful Sound was much like it is now: miles away from anything, across the mountains from the far western arm of Lake Manapōuri; a two-storied wooden building swarming with sandflies and surrounded by an astonishing wilderness of the sort almost extinct in the rest of the world.

I remember very clearly sitting there in Room 8 of Rosedale Intermediate, Invercargill, preparing for our Deep Cove camp by learning about Fiordland’s geography and geology, its flora and fauna, its weather and its history. Our teacher wrote facts on the white board for us to copy down and gave us photocopied sheets we were to paste onto the pages of our exercise books.

Most young people, certainly those with a regular-sized inclination to ingratiate themselves with their teacher, would have glued their hand-outs into their books, applied a title, and then moved on to other tasks: graffiti-ing their pencil cases with NKOTB Sux or coveting their classmate’s Kozmik sweatshirt, or fixing their hair bobble.

Not 12 year-old me. Twelve year-old me went to worrrk.

I turned those copied-down facts into landscape paintings, colouring them in to within an inch of their two-dimensional lives. I drew titles employing serif-heavy fonts of my own “design” and others using several different Lettering Book techniques, sometimes all within the same word. I was so excited by my work that even the headings had exclamation marks: Deep Cove! A Tipical Fiord! (Spelling author’s own.) An Over Deepend U-Shaped Valley! Hanging Valley or Cirque!!!

I decorated the geography hand-out to the north, south, east and west; the page describing red horopito and rimu is cross-hatched in a garish sort-of-Tudor pattern in purple and yellow; there is shading of myriad colours that cover entire pages — a commitment to crafty-colouring-in that would make even Suzy Cato blush.

Is the map hand-out coloured in? Shit yes it is. Coloured orange on the frontside and the back, then folded into the shape of a pup tent and stuck into a coloured-in field. Colours aren’t enough on their own, though. I wanted shapes, too. Random shapes that have nothing to do with the subject at hand. There are parachutes above the letters spelling out roche moutonnées; there is a maypole that joins plant species; the lettering of “Manapōuri Power Scheme” is made to look like a jelly-tip ice-cream; the “Places and Names of Fiordland” page is inexplicably rendered as a Christmas present.

My classmates must’ve wondered what the hell was wrong with me. I am wondering what the hell was wrong with me. I don’t recall any of them asking, or seeing their looks of disdain, but maybe they did and I just didn’t hear or see them for the screaming earnestness in my ears and the rainbows of steam rising from the tips of my coloured pencils.

“This is,” my husband says, “like something a crazy person would do.”

His unusually high-pitched voice attracts the attention of our kids.

“What is this?”

“It’s my social studies book from when I was 12,” I tell them. “The school work I did about Fiordland before I went to school camp there.”

The seven-year-old says, “Did your teacher even allow that much colouring?”

The 10 year-old says, “Jeez Mum. You needed to calm down.”

Page 8: Behold an accoutrement of candy stripes in baby blue and pink. The hand-out on geology is folded and tied up — give us a moment while my husband wipes the tears from his eyes — with a ribbon. The “Forest Structure” sheet is folded and coloured to form a tree trunk; the “How Do We Get There?” title, in irregular purple block letters, falls away down the pencil-sketched hillside like my credibility.

The book my husband and I hold between us displays a passion for its subject matter that goes well beyond nerdy appreciation — it is bordering on unhinged. It is the work of a 12 year-old with no care for making friends, just a single-minded vision involving all the colours of Crayola. A pre-teen so moved, she vomited the entire panettone colour chart onto her 1B5.

I just … I really loved Fiordland.

I still do. Witness the array of books and rocks and maps in my Auckland home that’ve flown up from the latitudes around 45 south: I’m a card-carrying Fiordland fan-girl, certifiably obsessed.

I had thought that obsession had started as an adult. That, as a grown-up living amongst the pōhutukawa and hibiscus at the other end of country, I’d become increasingly fascinated by that mossy, damp, faraway land. In fact, I’ve written magazine articles saying that very thing. But the evidence to hand suggests I was wrong about that, too. My absolute devotion to Fiordland was clearly well established — and rendered in such terrible technicolour — way back when I was 12.

Thirty years on, my novel begins where that old school exercise book ends, with a young girl enamoured of the forest she’s lucky enough to visit and her belief, just like I had back then, that something important and mysterious and ancient was hiding amongst those primordial trees.

Spark Hunter is fiction, a fantasy even, but it’s not too much of a stretch to imagine the events of the novel occurring in a place like Fiordland. It is a landscape of shadows, Ata Whenua, Te Rua o te Moko; it holds on to its secrets. It is a place that has attracted many explorers, adventurers and sightseers over the years — a place so beautiful and wondrous, but also so vast and precarious, that many who went in, never came back out. It’s true that there are parts of that forest where even now, in 2021, humans have never set foot. As one of the characters in Spark Hunter says, anything could be hiding out there.

No wonder I was so keen on the place, eh?

Books are hard to write. They require a level of commitment and patience that, for someone who spent 20 years in the business of fast-turnaround television news and current affairs before she attempted to write a full-length work of prose, feels painfully slow and hard-wrought. Study and perseverance, working and re-working: writing a book requires a good deal of nerd.

My novel has taken me years to finish, in between babies and kids and work and study and life, but I kept going because that story and its setting were stuck, glued with school-strength PVA, into my psyche. My mad pre-teen colouring over hand-outs about lichen and horopito and hanging valleys — that stuff stayed with me. It has helped me make Spark Hunter into the book that 12 year-old me would’ve wanted to read. Just like my old exercise book, it’s a love letter to Fiordland, both for kids like me then, and adults like me now, who nerd out on the green and the wild and the wonder of it all.

In 1991, my Room 8 teacher, who must’ve been crying with laughter at the multicoloured earnestness of her student, wrote a note in pencil at the end of my exercise book:

“You have illustrated it very well, with a lot of extra effort put into it,” she deadpans. “In years to come, you will enjoy reading back through this.”

Spark Hunter, by Sonya Wilson (The Cuba Press, $25) was meant to be available everywhere today but Unity is still waiting on stock – it should land at any moment, so you can and should pre-order via the Wellington or Auckland store.