Veteran sports hack Joseph Romanos reviews My Life, My Fight by Steven Adams with Madeleine Chapman.

Disclaimer: Madeleine Chapman is a staff writer at The Spinoff. This review was commissioned independently by our books editor, Steve Braunias.

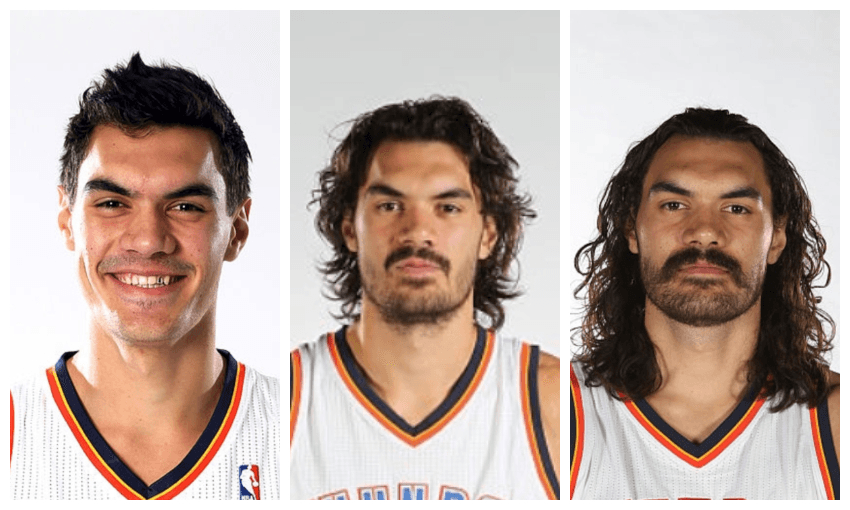

To judge by his autobiography, Steven Adams must be about the most down-to-earth, unprepossessing 25-year-old multi-millionaire on Earth. He’s progressed from the unmotivated, poor youngest child in a family of perhaps 14, perhaps 20, brothers and sisters (no one seems exactly sure) to an NBA basketball star and one of the most famous New Zealand sports stars of his era.

In fact, if I think of our most globally famous sports stars, I come up with Adams, Michael Campbell, Bob Charles, Edmund Hillary, Jonah Lomu, Lydia Ko, Jack Lovelock, Bruce McLaren, Wynton Rufer, Peter Snell and John Walker. Who of them was more famous worldwide than Adams? Certainly Hillary, and probably Walker and Snell. The rest? Adams at least matches them, and he’s really only just starting. In terms of world recognition he has even surpassed his half-sister Val, and she has two Olympic shot put golds and a silver, plus four world outdoor titles.

Yet, as readers learn in My Life, My Fight, Adams never really took up basketball seriously until he was in his teens. Within a few years he had been recruited by the Oklahoma Thunder in one of the most competitive sports leagues in the world and was rubbing shoulders with NBA rock stars like LeBron James, Kevin Durant, Russell Westbrook and Stephen Curry.

The book dispels a few myths that have floated about concerning Adams. He was never a gang member, or even a street kid. He had not embarked on a life of crime by the time he was a teenager. In fact, he was struggling to get by in Rotorua, especially once his father Sid died. He was seldom attending school and instead spending his days playing Xbox. His was at his happiest when he could visit his brother Mohi and work on his farm for a few weeks.

He didn’t have a lot going for him, but he had enough – he was extremely tall and he had some caring older siblings.

To say Adams is tall does not do him justice. His father was 6ft 11in and young Steve was 6ft tall at 12 and is now 7ft tall. When he walks along a footpath, people notice. Not surprisingly he tried his hand at basketball, though initially without particular enthusiasm. An older sister, Viv, was the closest thing he had to a mother for much of his youth and some of his brothers looked out for him. It was an older brother, Warren, who set Adams on his life path when he drove him to Wellington at 14 years old. Warren, who lived in Wellington, took him to a basketball camp which Steve, out of his depth socially, barely tolerated.

That set in train the most amazing events. A few months later Warren rang Viv and asked if Steve wanted to return to Wellington and try to make a go of basketball. So Steve packed up his belongings, which fitted into a sports bag, and headed south with his older brother. He was befriended by a series of the most generous-spirited people imaginable – Warren, Blossom (a real-life saint to read Steve’s account of all she did for him), several teachers, most notably Glenda Parks and Ms Milne, Debbie and Chris Webb, physical trainer Gavin Cross and famous (in New Zealand) basketball coach Kenny McFadden.

Their kindness, unselfishness and sheer humanity enabled a boy who had had only a fleeting recent acquaintance with school to become a student at Scots College, Wellington’s prestigious boys private school, and to develop into an intimidating and skilled basketballer. They drove around him endlessly, picked him up so early it was still dark, fed and clothed him and, in McFadden’s case, trained him to be a sports champion.

But Adams does not shy away from all the hard work he did, too. I found it amazing that he (“not a morning person”) had the discipline to get up at 5.30am and submit himself to McFadden’s gruelling and demanding training sessions every day. That sort of commitment requires special character, and Adams obviously must have had it. Along the same lines, when he learned he would need some scholastic qualifications to gain entry into the American college system on a sports scholarship, he applied himself and did tolerably well.

I was very pleased, in the final mop-up chapter, to read that Adams in his own way is repaying others for the kindness shown to him. Throughout the book he speaks fondly of the Webbs, of Blossom, of his Wellington age rep basketball team-mates, of some teachers at Scots College, of McFadden and the rest. But they’re still in New Zealand and he has more money than he could ever want – his last contract was worth $US100 million. So it was warming to read that Adams gives back in his own way. A basketball scholarship at Scots College, his Steven Adams basketball camps, buying equipment etc when it is required. There’s not a fuss made of his generosity in the book, but enough is said for the reader to know he understands how fortunate he is that others looked out for him.

Adams touches on why he has never played for New Zealand, but the subject, dear to many New Zealand basketball fans, is dealt with in a paragraph or two and somewhat fudged over. As best I can gauge, he has not really bothered about playing for our national team because he has no particular affinity to New Zealand basketball administration. He mentions more than once how some good young kids (including him) could not play for national age teams because their families could not fork out the thousands of dollars required. That didn’t sit well. Also, of course, his loyalty is with the Oklahoma City Thunder, who are paying him so much money.

For basketball aficionados, there is enough to satisfy without the book ever plunging into a tedious match-by-match account of a season. I was struck by the short period when he was being courted and studied by various NBA franchises before the 2013 draft. Los Angeles-Boston-Dallas-Los Angeles-Oklahoma City-Philadelphia-Salt Lake City-Cleveland-Minnesota-Chicago-Phoenix-Oklahoma City-Atlanta-New York – a mad swirl of travel, schmoozing, questions and basketball. Imagine what it must have been like for a 19-year-old with Adams’ background.

Eventually he was 12th pick in the draft, chosen by the Oklahoma City Thunder, who liked his size, willingness to work and potential. Since then, the Thunder have generally been there or thereabouts without managing to nail a championship, and Adams has developed into a key player on the team and one of the NBA’s bankable stars.

It’s heady stuff, unbelievable really. A fiction writer wouldn’t have dared script that path for the lost youngster in Rotorua, but Adams has done it. All power to him.

A word about the author. Madeleine Chapman had never written a book. She knew Adams through their shared time in Wellington basketball. When he wanted his story written, he asked Chapman and she leaped at the challenge. It proved to be a good partnership because the book captures Adams well – understated in manner and with a strain of humour running through it.

My Life, My Fight by Steven Adams with Madeleine Chapman (Penguin Random House, $40) is available at Unity Books.