Dominic Hoey’s new novel is a sharp jab from the heart of life on the poverty line in Aotearoa. Full of dark humour, gritty action and many shades of love, it moves at pace alongside lead character Monday Woolridge as she fights her way through obstacles and opportunities.

There was something sticking into my arm. It took all my strength to lift it to eye level. A needle dug into my skin just above my elbow, a tube running off it. I followed it with my eyes and saw a bag filled with clear liquid hanging above my head. I’m in a hospital, I thought, which means I’m in Auckland. I freaked out and tried to get out of bed but the pain in my legs was intense.

“Hello?” I croaked. “Nurse? Doctor? Anyone?”

I heard footsteps and then the door swung open.

“You’re not dead after all.” A short woman in a nurse’s uniform stood in the doorway holding a phone. “Doctor Pearson said you would probably die.” She looked at her screen. “But he’s been wrong before,” she said, texting. “Usually the other way though.”

She walked into the room, shoes slapping against the lino, and stopped at the bed, pulling back the sheet so she could look at my legs. They were bandaged but damp, kind of squishy. “Oh dear.”

She was probably my age, I guess. She had fat cheeks and a lazy mouth that hung in a permanent frown. Her hair was like straw, which made me dislike her for some reason.

“Any luck, you’ll keep the legs.” She looked at them again. “Yep, they’re proper fucked.”

Every time I swallowed it felt like someone was pouring boiling coffee down my throat.

“Can I have some water?” I asked.

“There’s a jug right there,” she said, pointing to a bedside table.

“Is it empty? Bloody Susan.”

She grabbed the jug. “Susan, you big bitch!” she screamed, storming out of the room, taking the jug with her.

It wasn’t easy, but I managed to lean over and pull the curtains back. Instead of looking down onto Grafton Road I was in the town outside the village. The medical centre was bigger than I’d thought. Across the road was the library. A couple of teenagers sat out front on their phones. I leaned back in bed and sighed with relief. I might be about to have both legs cut off but at least the fucking Hastings brothers weren’t going to burst through the door.

I pulled out my phone. I tried to take my mind off Thailand and got onto the hospital Internet. It was slow as fuck but better than up Phone Hill. I was hoping Teuila would have messaged me back, but there was nothing. I went and looked at photos of her honeymoon. They were in Bali, swimming and drinking, her stupid husband pulling the same dumb face in every photo.

“Fuck you,” I hissed at the screen, then realised there was someone else in the room.

“I’m Doctor Pearson.” A tall skinny man in a white coat was standing at the foot of my bed looking at me solemnly. “How do you feel?”

He was too young to be a doctor. He looked like he could have been mates with Hope. Under the white coat was a loud Hawaiian shirt. His hair was slicked back and greasy.

“Not great.”

“Well, you’ve got sepsis. It’s pretty serious, but you should be OK.”

He scratched the back of his head and then examined his fingers.

“The nurse said I’d be lucky to keep the legs.”

His face dropped. “Oh God, she wasn’t meant to tell you that.” He lifted the sheet with his thumb and forefinger. “I mean your legs are a mess, but you’ll get to keep them.”

He looked round the room and then shrugged. “I’m hungry,” he said and walked out.

I lay in bed staring out the window, watching the clouds float past. I knew I had to get the fuck out of there, but how would I make it back to the village? There was an old piece-of-shit TV stuck to the wall, but no remote. Looking at my phone was just making me depressed, seeing all those photos of people from my gym training and Teuila living out her middle-class fantasies. I lay back, drifting into an uneasy sleep. I dreamed of swimming in the lakes while the Hastings brothers waited on the shore.

“How many working days have I been here?”

The nurse screwed up her face. She was wiping gunk off my legs.

“What do you mean?” she said.

“Like how many weekdays?”

“I don’t know.” She sounded annoyed by my question.

“Is there a remote for that TV?”

“Nah, someone pinched it.” She finished up with my legs and covered them. “Doesn’t work anyway.” She threw the dirty cloth into the bin on her trolley. “How did you do this?” she asked.

“Kicking a bag of sand.”

“Ahh,’ she said knowingly. ‘Thought you had a meth vibe about you.”

The next day they got me out of bed to see if I could walk. Doctor Pearson and the nurse helped me stand up.

“Try putting your weight on your feet,” the doctor said. I slowly stood on the cold floor.

“How’s that?” he asked.

“Good, I think.” It hurt like fuck but I wanted them to let me out of there.

“Try walking by yourself.”

Doctor Pearson and the nurse let go of my arms. I took a few steps. It was sore, but not unbearable. I turned around and started walking back towards my bed and fell on my face. The doctor and nurse looked down at me.

“Do you think we need to increase the antibiotics?” the nurse said.

“Yeah, and give her some pain relief.”

Thank the opioid Jesus for morphine. It made everything seem manageable: the money, the passport, that my blood had turned against me, and there was a family of lunatics out to kill me. Every time I heard those problems mumbling in the wilderness of my brain, I just pushed down on the button next to my bed and vaporised them.

At one point my phone started ringing. It had been so long since I’d had reception, it gave me a fright. I slowly held the screen up to my face and almost dropped the phone. The name Romeo took up the screen. I sent the call to voicemail and stuffed it under the bed and went back to floating in a warm morphine tide.

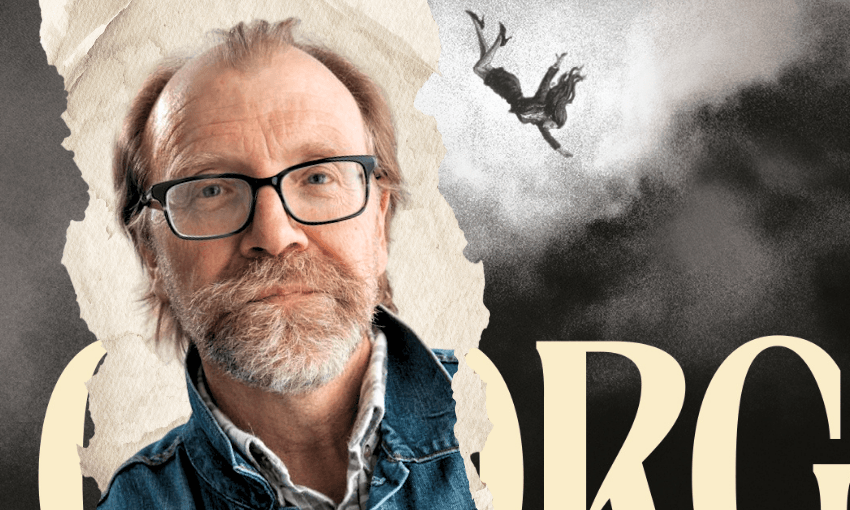

Poor People With Money by Dominic Hoey (Penguin Random House NZ, $37) is available from Unity Books Auckland and Wellington.