The loss of innocence, the revitalisation of te reo, the rising up of women and of LGBTQ rights – the decade has been a ride. Here are our pick of the books Aotearoa wrote along the way.

All Blacks Don’t Cry by John Kirwan, 2010

The book that launched JK’s second career: mental health campaigner and catalyst to hard, important conversations all over Godzone. Think how much better we are at talking about mental health now! A large part of that, I reckon, is down to JK.

I remember reading an advance copy in the newsroom of the Sunday Star-Times, yelping at my colleagues every so often. “You guys John Kirwan is freaking out so much he’s thinking about killing people!” “You guys now John Kirwan is thinking about killing himself!” I was a twerp.

Halfway through reading I got a call; my grandpa was in hospital. Heart attack. I packed the book – Grandpa enjoyed books, and rugby, and he was reading way too much Ian Wishart – and flew to Napier. Grandpa didn’t recover enough for any reading. I still wish that he had read this book, and that we could’ve talked about it: about depression and anxiety and self-care and communication, and how those things play out in our family, and how immensely brave it was of Kirwan to boot his vulnerabilities into public view. / Catherine Woulfe

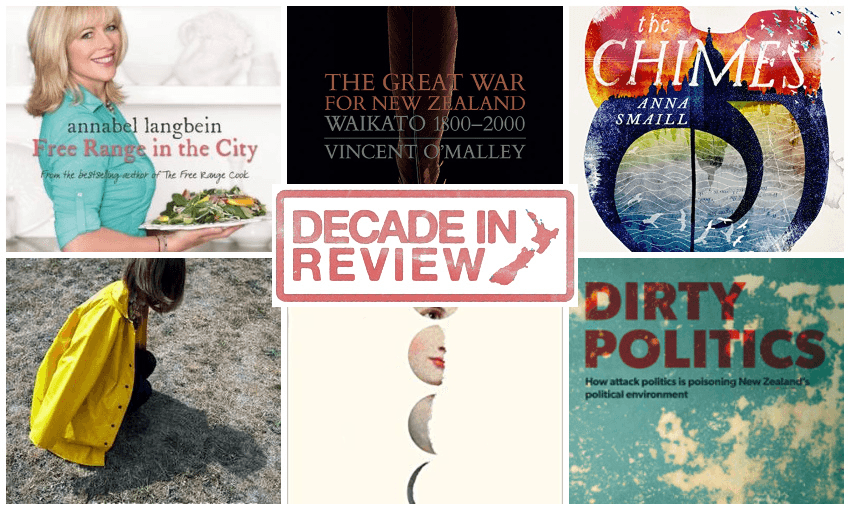

Free Range in the City by Annabel Langbein, 2011

WTH is Annabel “hop in your jetboat to forage for raspberries” Langbein doing on this rarefied list? Free Range in the City deserves the slot because it was a mega-seller, because Langbein continues to dominate the local cookbook scene, and because the whole free range thing neatly sums up the blessed naivety of the first part of the decade.

Ten years ago, what the people who buy cookbooks cared about was growing rocket on their balconies and bunging it into scones. That was what we called “sustainable”. And it felt really good!

The cover features Langbein in a turquoise shirt, sleeves rolled up like she’s just itching to shell a washing basket full of broad beans. (This was a development on her 2010 monster The Free Range Cook, where she wears a turquoise cardigan and looks slightly baffled, a look she has not worn since).

Now, Free Range in the City has taken on a sort of second life: all those family picnics at the beach, those long weekend lunches, function as a recipe for how to get on with things regardless. / CW

The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton, 2013

Winner of the Man Booker Prize and about to become a BBC 2 miniseries, Catton’s second novel is famously long and complex: it’ll either do your head in or light you up, but it’s a sitter for this list, the first book we decided on. The story is set on the West Coast in 1866. There is a goldrush. There is a murder. Catton organises the characters and chapters according to the signs of the Zodiac, planets, etcetera; on top of that the length of each chapter changes to represent the lunar cycle. Ye gods. / CW

Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History by Aroha Harris, Judith Binney and Atholl Anderson, 2014

In 2016 a panel of experts assembled by the Spinoff picked this as the greatest work of non-fiction by or about Māori ever. They said of it:

Like a supergroup of historian rock stars producing the best album of all time. Far from succumbing to triumphalist history, Tangata Whenua meets Māori history on its own terms and rejects some of the comfortable assumptions of a flawless pre-colonial society. That’s valuable, but the book’s lasting legacy is how it expands the scope of Māori history, weaving together knowledge from archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, law, political science and of course oral history. This is theory at its finest, it resists treating its subject in isolation, instead searching for connections to make sense of the world as we find it.

Dirty Politics by Nicky Hager, 2014

Oh, the blessed naivety of 2014.

Māori Made Easy: For Everyday Learners of the Māori Language by Scotty Morrison, 2015

Despite the upswing of interest in learning te reo Māori this decade, there are very few learning resources available, and fewer still from recent years. Scotty Morrison’s Māori Made Easy series doesn’t just fill a gap in the market though – his 30 minutes a day for 30 weeks programme is elegantly simple and understands that learning te reo Māori for some people is an unlearning of trauma too.

It’s a bestseller that has changed the language learning landscape in classrooms and outside of them for all New Zealanders. Like a modern day AW Reed, Morrison’s books will become a staple of every New Zealand bookshelf in years to come. / Leonie Hayden

The Chimes by Anna Smaill, 2015

In 2013 New Zealand finally passed legislation allowing same-sex couples to marry. Two years later Anna Smaill released this novel in which the young protagonist is gay, but that’s by the by – the important thing is that he’s in love.

The Chimes is weird and gentle-but-horrifying and quite gobsmacking, and it won the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel in 2016. Summarising the plot makes it sound entirely batty. We’re in London. The populace is controlled by an enormous musical instrument, the Carillon, which sounds every evening and in doing so wipes clear all memories of the day. (The Guardian called it “a kind of omnipresent tinnitus”). We follow a gang of young outlaws on a river journey.

Smaill gives her world gravitas and layers – networks of tunnels, actually – and she is so confident in its peculiarity that after a few pages you stop questioning and go with the music. / CW

Can You Tolerate This? by Ashleigh Young, 2016

A book of essays. The New Zealand book of essays. The New York Times gave their review a hilariously New York Times-y headline: ‘In Essays About Bodily Ailments and Other Conditions, Clues to Writing – And Life’. I mean it does the job, but also, lol. In the review they said things like “a lovely, strange and profound debut” and “an essay collection unlike any I’ve read”.

If you could pin the boom in local creative nonfiction to a single book you’d pin it to this one. And it’s undoubtedly the book that Young has to thank for the sweet sweet Windham-Campbell Prize that was sprung on her the following year, worth US$165,000. A few days after the win she told The Spinoff: “I’m not capable of processing in my head that amount of money. The most immediate thing I can think of is that I can buy a table and a chair for my living room so I can write by the window.”

Millenials! Honestly.

We had to smuggle her book onto this list because Young, now our poetry editor, would’ve deleted it immediately. / CW

Hera Lindsay Bird by Hera Lindsay Bird, 2016

Hera Lindsay Bird’s poem ‘Keats is Dead So Fuck Me From Behind’ broke the internet, and then her eponymous collection seemed to break New Zealand poetry. A lot was made of its sexual content, but what was and still is really shocking about this book is its poetic brilliance – its wicked intelligence, hilarious litanies, and riotous beauty, and how all of these qualities were in full force when she was sending up poetry itself. As Steve Toussaint has pointed out in his essay ‘TMI’, Bird also magnificently trashed the old dictum that we should never assume that ‘the speaker’ of a poem is the poet themselves. ‘My name is Hera Lindsay Bird,’ she declares. ‘This book is called Hera Lindsay Bird / I wrote it, and I mean at least 75% of it’. It’s partly her direct experience that gives her poems their emotional weight – the peeing in a supermarket, the frustration with poetry (‘What’s the point of saying new things?’), being in and out of love (‘Love comes back / from where it’s never gone…It was here the whole time / like a genetic anomaly waiting to reveal itself’). Bird was criticised, feebly, for many of these poetic transgressions, which only made her work shine brighter. In the end, Hera Lindsay Bird is transgressive simply by being mind-bendingly good. / Ashleigh Young

The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800-2000 by Vincent O’Malley, 2016

The extent to which the New Zealand wars were predicated on deception and corruption had been obscured until Vincent O’Malley’s The Great War for New Zealand. He brings into sharp relief the brutal and unjustified attacks on Waikato iwi and the subsequent theft of land as punishment, and finally tells some of the untold tūpuna stories of the battles themselves, passed down from generation to grieving generation. It draws a clear line from colonial abuse of power to the problems we face as society today. Naming those events has already changed our thinking as country in immutable ways, sparking a campaign led by students to make New Zealand history a compulsory subject in schools.

As O’Malley concludes at the end of the chapter titled ‘Owning our history’: “None of this requires feelings of guilt or shame, but simply a willingness to hear, read and embrace the difficult aspects of our past. And buried within this tale of loss and waste, with all of its attendant grief and misery, we might even find some uplifting elements if we look closely enough.” / LH