Kiran Dass interviews Mark O’Connell, whose new book sprang from terror about what climate change meant for his kids.

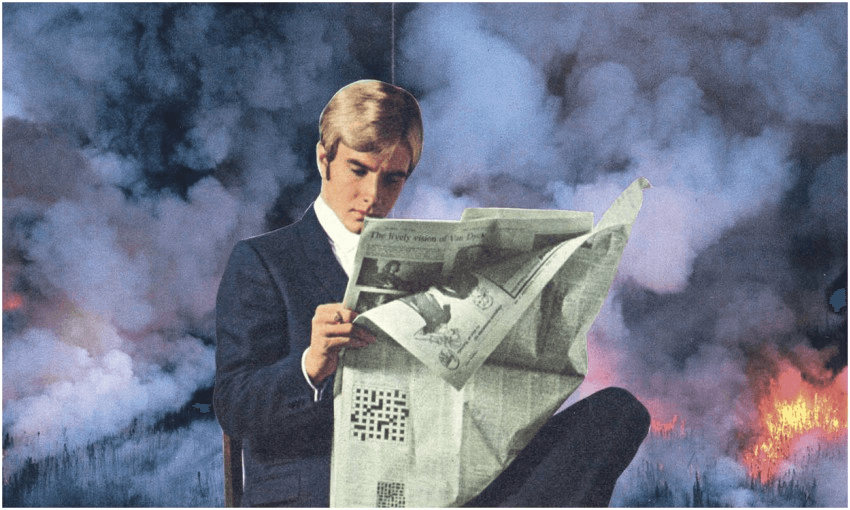

Dublin writer Mark O’Connell reckons we’re alive in a time of worst-case scenarios, and that we can only really survive in a meaningful sense as part of a community.

Following his first book, 2017’s To Be a Machine: Adventures Among Cyborgs, Utopians, Hackers, and the Futurists Solving the Modest Problem of Death, his new book Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back is a thoroughly engaging work of reportage where he seeks out preppers – a subculture of people prepping for the end of the world, the great civilisational crack up.

It was triggered by “a surge of shame and sadness at the world my son would be forced to live in”, he explains in the opening chapter. “It was not obvious to me how a person was supposed to raise children, to live and work with a sense of meaning and purpose, in the quickening shadow of that future … Listen. Attune your ear to the general discord, and you will hear the cracking of the ice caps, the rising of the waters, the sinister whisper of the near future. Is it not a terrible time to be having children, and therefore, in the end, to be alive?”

Fittingly, it’s also his children that help him arrive at some sort of peace – or at least an ability to dance and blow raspberries. The book is equal parts terrifying and hilarious. O’Connell attends a conference in Los Angeles about the colonisation of Mars. He visits the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, people hawking South Dakota bunkers, and a wilderness reserve in the Scottish Highlands. There’s a brilliant section in which he reads his son The Lorax: “If it’s not an outright work of postapocalyptic nonfiction, then The Lorax is about as close to being one as an illustrated book for preschoolers has any business being.”

And on a New Zealand road trip, he investigates why tech billionaires like Peter Thiel are buying up property in New Zealand in anticipation of civilisational collapse. He had been corresponding with art critic Anthony Byrt; they visit the Michael Lett gallery to view sculptures by Simon Denny that present “a Thielian vision of the country’s future”. Jacinda Ardern waves as she is whisked past at Auckland Airport. He sits outside a Nando’s and marvels at the birds hopping around the tables. Matt Nippert makes a cameo appearance. Written with a clear-sighted eloquence and a startling knack for the absurd and comic, this is seriously a book about right now.

The Spinoff: Kia ora Mark! How is your lockdown in Ireland going? How have you been spending it?

MOC: I can’t complain, in the greater scheme of things. The lockdown has eased in the last few weeks here, so we’ve been able to move around a lot more. I’ve been out of Dublin for a few weeks now. I just took a trip to Co Kerry, where I’d never been before – absurdly, given how small Ireland is. One effect of the lockdown is that I’ve come to appreciate the things that are close to me more.

What is the mood there at the moment?

It all feels a little purgatorial still. There’s a lot of talk about the inevitability of a second wave, and a lot of uncertainty about whether schools will be back in September, and in what form. It’s nothing like the darkness and anxiety of a couple of months ago, though.

I started reading Notes From An Apocalypse right at that uncertain and anxious moment when New Zealand went into alert level four lockdown in response to Covid-19. So it was freighted with a piercing kind of anxiety and prescience. At the same time as reading your book, I re-watched the old BBC shows Threads and Survivors (and also thought a lot about the writer J.G. Ballard) so it was a full-on immersion into civilisational collapse. I don’t know what I was thinking!

You sort of did the same thing in writing this book – facing your personal anxiety by jumping into the fire – seeking out places, ideas, phenomena that seemed to be especially charged with anxious energies?

I also watched Threads when I was in the early stages of writing the book, and I also read a fair amount of Ballard too – a writer with whom I have a complicated relationship. I don’t love his fiction, but I can’t help admire his weird prescience, his instinctive understanding of where we were all headed. I’m wary of rationalising the writing my book too much from a psychological point of view, as though it was the result of a conscious effort to deal with my own anxiety. There’s an element of that, but I think mostly it was just a matter of this being the subject I was overwhelmingly preoccupied by at the time. Everything seemed to be about the end of the world, and I felt like it was the only lens I could think through.

I can’t actually think of another book that has been published at such an uncannily perfect time, especially considering how Covid has wreaked havoc with so many publication dates. I read an interview with you where you say that you received a box of the freshly minted book from a delivery guy wearing a mask, and you opened the box while wearing plastic gloves. What were your thoughts at the time of all this?

It all just seemed a bit too on the nose. I would honestly have liked the book to be a lot less timely. One of the ironies around it, though, was that so much of what I write about in the book has to do with people profiting from apocalyptic anxieties, apocalyptic scenarios – and here I was, benefiting in this weird way from the timeliness of my book.

Tell us about the catalyst for you to start writing this book and how did you go about preparing for it?

I’m not a great preparer – in life, or in art, ironically, given that preparing, or preparedness, is sort of a major theme of the book. I had been thinking a lot about anxiety for a while, as a state of being and as a theme for writing. Anxiety about the future, particularly in relation to being a parent, had been a big thing for me for a while. I knew I wanted to write about that in some way. But it wasn’t until I started to become interested in apocalyptic preparedness – in Doomsday Preppers, and people who were convinced the end of the world was in some way or other nigh – that I found a way to write about that anxiety. The idea of the apocalypse worked as a kind of metaphor for me, a thing I could use to contain the fairly formless cluster of themes and preoccupations I was working with.

Over lockdown I also dis/comfort re-read bits of Mark Fisher (the brilliant cultural critic who took his own life in 2017) – Ghosts of My Life and The Weird and the Eerie. And I kept wondering what he would make of everything that is happening in the world right now. I found myself dumbly wishing he was still around and still writing – that that would help us understand or give us a different angle. I kept thinking of the line “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism”, and then when I read your book at the same time, I’m sure you quoted that line, though in re-reading the book now, I can’t find the part where you mention it. In Ghosts of My Life he writes about how we are haunted by futures that failed to happen. What do you think?

I allude to it, or paraphrase it, in the New Zealand chapter. But yes, I think that’s very true. I think Elon Musk is a great – or terrible – example of that. His whole Mars colonisation enterprise is such an obvious exercise in nostalgia for a lost future. Nobody really talks about the future as a realm of possibility and progress anymore, not in the way they did in the late 20th century. And I basically agree with Fisher that much of this has to do with the widespread melancholy acceptance that capitalism is inescapable.

International travel is so out of reach now. The book sees you travel to the Scottish Highlands, Los Angeles, South Dakota, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone and New Zealand. How did you decide where to go and how did you narrow it down? What were some other places you wanted to visit but couldn’t?

It was probably more haphazard than the book makes it seem. I was going to go to Svalbard in the Arctic Circle to visit the Global Seed Vault, for instance, but it never panned out. But then I hadn’t planned on going to New Zealand, and that just sort of happened unexpectedly, so it netted out.

The New Zealand chapter is terrific. You’ve said that “if you’re interested in the end of the world, then you’re interested in New Zealand.” Peter Thiel has referred to New Zealand as a “utopia”. New Zealand’s relative remoteness and stability is obviously attractive to privileged end-timers. What were your impressions of New Zealand and the insights you gained from the people you spoke to while you were here?

I really loved it, as I guess is obvious from the chapter. One thing that really struck me about New Zealand when I was there, and has stayed with me since, was how seriously the country seems to take the complexities of its own colonial past, and the work of overcoming the wounds of that past. Obviously there are major inequalities in the country’s makeup, but I really did get the sense that those issues were taken seriously. Of course, this is an outsider’s view, and probably overly simplistic, but that was my impression.

You set out looking for Peter Thiel’s properties in Queenstown and Lake Wanaka, what were you expecting to find there?

I knew there wouldn’t be any kind of Bond villain lair on the property, that it was just basically a sheep station, so it wasn’t an anticlimax or anything. My worry, in writing it, was whether I’d be able to pull off this situation where, in the context of writing this book about the end of the world, I’d travelled all the way to New Zealand in order to go to an art exhibition opening and cycle around a lake. I feel like I did in the end, but it wasn’t easy!

You ask the question that if “wealthy foreigners were buying land here and building literal bunkers, fortifications beneath the ground of this country that had welcomed them in the first place, what did that say about their motivations, their view of life?” What conclusion did you come to?

It’s important to say that I didn’t see any concrete evidence, so to speak, of literal bunkers – and I was as interested in the perception of this stuff as I was in the reality. But I think it speaks to the paranoias and inequalities of our time. I think bunkers exist as constructed metaphors for underlying political and economic structures. When you’re talking about luxury bunkers and survival communities and so on, you’re always also talking about capitalist individualism, and the damage it does to the relations between people, the idea of society.

Of all the people you met and wrote about – preppers, tech billionaires, bunker hawkers – what were the things that unified them?

Just that – a deeply individualist understanding of the world.

At one point you write that there was a suspicion that “I might not be as different from them as I like to imagine …” How did you negotiate that?

There were definitely moments where I identified with the anxieties of preppers. The movement arises out of a sense of the instability of the structures undergirding our everyday life, and a fear of the unknowability of the future. I can absolutely identify with that. But the reaction of most preppers is to protect themselves and their families and their property against the perceived threat of society. And that’s an ideologically determined response. I think that not only do we have a responsibility to other human beings, but that we can only really survive in a meaningful sense as part of a community.

What is your instant reaction when I say the words “pasta primavera mix with freeze-dried chicken chunks”?

I see myself walking out into the nuclear rain.

“Those who are prepared will survive,” says Donna Nash in this 2012 clip from Doomsday Preppers, a show O’Connell binged hard while researching his book.

The book is filled with such sharp observations – seeing and noticing things. Things that are often at the edge of the frame. It has such a strong sense of narrative. Did you record everything as you went? What was your writing process to put it all together?

I recorded all the conversations that are in the book – or at least all the ones that were undertaken as interviews. But also I take, as they say, “copious notes”. When I’m reporting, I find myself going into a much more receptive mode than I usually exist in, where everything takes on a kind of heightened resonance, and so everything seems important. So I wind up with a lot of notes about things that have nothing to do in any direct way with the matter at hand, but which seem to me to be still vitally important – like, say, the little museum in South Dakota, or the birds flying around the Nando’s in Auckland. I write a lot of scenes out of this conviction that they are somehow relevant, and a lot of them never make it past a first draft. There’s a lot of stuff that goes nowhere, but that’s writing – and also life.

The book is at times hilarious. It’s impressive how it’s a travelogue and it’s reportage, and it’s terrifying, but it’s written in such a charismatic voice and is also entertaining and very funny. The tone is pitch perfect. Did you intend on it being quite as funny as it is?

Thank you! Humour is a really complicated question for me, and I have a pretty idiosyncratic attitude towards it. I want my writing to be funny, but I don’t ever want to go out of my way to write jokes. I basically hate writing that’s full of zingers and quips, I can’t stand it. I hate the comic mode in writing. It’s like stand up comedy, in that the concerted attempt to be funny basically guarantees that it won’t be. For me, things usually wind up being funny in writing just as a result of describing reality as faithfully as possible. The world is full of amazingly funny, terrifyingly absurd, charming things, and I think it’s my job as a writer to just describe them accurately.

I mentioned narrative. The book also reminded me a bit of the documentaries of Werner Herzog, Les Blank, Ross McElwee and the Maysles brothers: The running of a parallel personal story alongside a bigger issue, and a strong sense of the strange and absurd. Stories that you couldn’t make up but are unquestionably true. Sorry, that’s not really a question.

Well I’ll take it! Those are extremely flattering comparisons, and at least in the sense of what I am consciously trying to do, also accurate. I’m always getting compared to, specifically, Jon Ronson and Louis Theroux by British critics – and you can sort of see where they’re coming from. But I don’t feel much affinity for those guys. Whereas the Maysles and Herzog, on the other hand, loom very large in the thick fog of influence that surrounds me.

For the subject matter, the book feels hopeful, optimistic even. There’s a battle between despair and futility versus hope and optimism. And it’s as if by the end of the book you come full circle with your personal anxiety about the state of the world. Where did you end up?

I think there is a fair amount of optimism in the book – and in me – although it’s pretty fragile, and can be very quickly overwhelmed by despair. But I did want the book to reflect my own personal trajectory with these anxieties that I’m writing about. By the time I finished it, I was definitely feeling less despair and fear about the future than I was when I started out. A lot of that had to do with personal reasons, most notably having a second child, and making more space for joy in my life. It was also a very hard book to write, and the mere fact of finishing the book lifted my spirits. Some of that lightness makes it into the closing section of the book itself. Finished at last with the end of the world!

It didn’t surprise me to learn that you have a background in literature. Notes From An Apocalypse is so beautifully written. You wrote your thesis on the work of John Banville, one of my favourite writers. What was it about his writing that appealed to you?

Firstly the prose. I can’t think of a more beautiful prose writer than Banville. But also he is a great example of what I was saying above about humour. He’s incredibly funny, but never in a way that involves writing comically. I find his sensibility hugely appealing – this sort of bleak and weary but also deeply humane view of the world.

I gravitate to Irish writers – yourself, Sally Rooney, Jessica Andrews, Sinead Gleeson, Eimear McBride, Wendy Erskine, Kevin Barry, Mike McCormack, Sara Baume, Anna Burns, Anne Enright, Edna O’Brien. And I know he’s Scottish but David Keenan’s tremendous novel around The Troubles For the Good Times … And I wonder if there is some kind of innate psychic connection/psychogeography between New Zealand and Ireland. Have you read any New Zealand authors?

Shamefully, I have not! The two New Zealand writers I have read are, predictably, the two living Booker winners – Keri Hulme and Eleanor Catton. I also haven’t read David Keenan, but I’ve heard that book is amazing. Anthony Byrt, in fact, has assured me I’d love it.

What are you working on next, Mark?

Right now, I’m working on a theatrical adaptation of my first book, To Be a Machine. An adaptation so loose it almost has nothing to do with the book. I’m working on it with a company called Dead Centre, who is a very exciting theatre group based in Dublin and London.

I’d love to know what you have been reading lately and what you are looking forward to reading next?

I just finished a book called Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima, which was stunning. And right now I’m re-reading J.M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello, and Mr Personality, a book of pieces by the New Yorker writer Mark Singer, which is brilliant. I’m also really looking forward to Ottessa Moshfegh’s new book (Death in Her Hands). And the Irish poet Doireann Ní Ghríofa has a non-fiction book coming out soon called A Ghost in the Throat, which I read a proof copy of earlier this year, and it’s really extraordinary.

Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back by Mark O’Connell (Granta, $32.99) is available from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.