Michael Field reviews a new study of Niue’s role in World War I, when Sir Māui Pōmare despatched 150 Niueans to fight in a mysterious war.

Millions of dollars have been spent in adoration of New Zealand’s mythology which says sending 18,000 men to die in the Great War made us a really great nation. Gallipoli, according to the articles of faith, turned Australia and New Zealand into blood brothers, while at the same time seizing Berlin through the back door (at least that was the idea).

That it was about dividing up the Middle East between the French and the British, and securing supplies of this new fangled thing called oil, escapes mention. It’s still debatable what World War I was even about: justice for a dead archduke, revenge for Belgium nuns, exasperation at Prussians wearing pickelhaubes or to give Peter Jackson something to do in his spare time with our taxes? Or was it peace, economic justice and democratic rights for white subjects of the British Empire?

Margaret Pointer’s new study Niue and the Great War does not explain the war – why lumber Niue with that responsibility? What she shows starkly is that even in a global war, politicians act in local interests and often without care for the wider outcome.

Such is the case of the first Māori to sit in cabinet: Western Māori’s Sir Māui Pōmare (1875/76-1930). He had cabinet responsibility for the Cook Islands which then included Niue, population 4000.

News of Archduke Ferdinand’s demise and New Zealand’s subsequent declaration of war made it to Niue 39 days later. By then, New Zealand had already occupied German Sāmoa, 600 kilometres to the north. Even Tonga, 600 kilometres the other way, had learnt of war (albeit a month later), prompting King George Tupou II to declare his kingdom would be a neutral. Britain reminded him that his fiefdom was not independent.

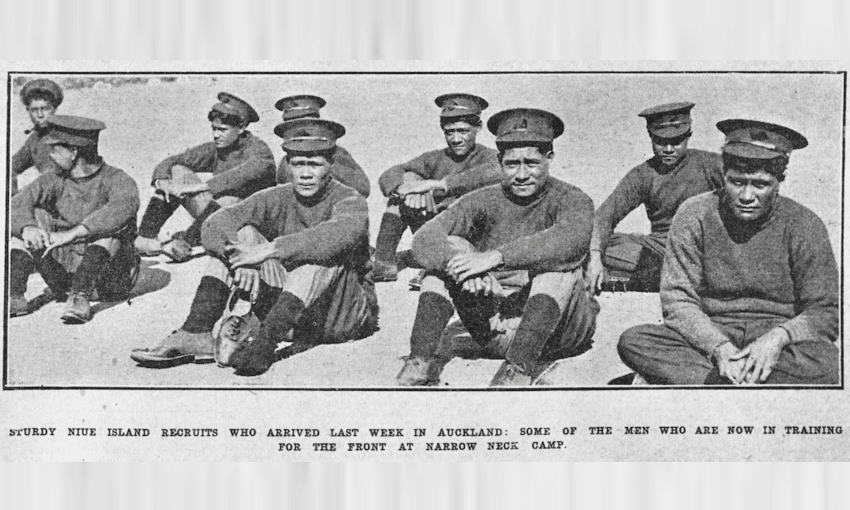

In 2000, Pointer, who lived on Niue, wrote Tagi Tote e Loto Haaku: My Heart is Crying a Little to tell the story of how New Zealand took 160 bare-footed Niuean men and, after training briefly at Narrow Neck Beach on Auckland’s North Shore, despatched them to the carnage. They lasted a year, most of them sick from cold, poor food and confusion about what they were doing.

In her new book, Pointer provides an explanation for New Zealand’s policy blunder in recruiting them. Her sight is set on Minister for the Cook Islands, Pōmare, a kind of early model Shane Jones; ebullient, boastful and short on actual results.

The Reform Party government (one of the begetters of the later National Party) and Defence Minister James Allen wanted more Māori men signed up. The Māori MPs were sent to get them. For the most part they were successful, but as Pointer notes, Pōmare’s constituency included Waikato and Taranaki, areas that during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s had suffered defeat and confiscation.

“They were not now prepared to offer their young men to fight a European war on the other side of the world,” Pointer writes. “His mana was threatened by opposition to enlistment in his Western Maori electorate.”

Other areas, such as Ngāpuhi, agreed, arguing that it violated the Treaty of Waitangi. Allen turned on Pōmare and told him that he should use his portfolio and get Cook Islanders and Niueans. Accordingly, Pōmare went to Niue in October 1915 to accompany the Niueans to New Zealand.

Pointer tells a story that a headcount on the ship revealed that there were 149 men aboard. Pōmare demanded another volunteer to round up the number. Finally, over opposition from his wife, Alofi policeman Peki Matagitakai agreed. When his wife Tapola heard, she swam out to the ship to say goodbye.

There is a problem with this story: is it true? Did it actually happen? Pointer needed to deal with it, but she’s failed to do so. She provides all the names of the Niueans who served – and Matagitakai’s isn’t among them. Nor could I find it in the marvellous Archives New Zealand files. Perhaps Matagitakai swum back to Tapola. We just don’t know. New Zealand’s Great War story is deeply afflicted with folklore and myths; academic writing is about confronting and seeking truth, but Pointer just gives us the myth, which may or may not be accurate.

Not all Niueans were in agreement with going to war. A mission teacher, Ikimatatoa, warned people not to sign up. “If a bullet went through a man’s body in battle, he told the congregation, it would also go through his soul, thus disqualifying the victim from entering heaven,” Pointer writes. “This dread fate, he explained, would only happen to those who went abroad to fight: if they waited until the enemy came to Niue and were killed in Niue, they would indeed be blessed.”

Two Niueans already in New Zealand, Hono Paufai and William Alfred, enlisted and found themselves at Gallipoli. Both were wounded, Alfred at Chunuk Bair and Paufai on Sari Bair. Paufai died from his wounds. Niue’s resident missionary, James Cullen, wrote of Alfred, saying he had “now retired on pension and with a crippled arm. Even little Niue has her share in the glory of that gallant though unavailing enterprise.”

The misery of the Western Front soon overwhelmed the Niueans and a year later, they were ordered off the lines, desperately sick. James Allen was angered at the decision; such retreat could lose the war.

If Niue is about anything, it’s that New Zealanders have a long track record when it comes to exploiting Pacific Islanders. Niue was perhaps the more extreme.

Pointer describes it as “a very sad story, a story of ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances, frightened, bewildered, uncomprehending, homesick, ill.” She argues the Niuean story has been embraced (although decades later) because of the disjuncture between South Seas island and the Western Front.

Niue’s smallness made its story more focused: “We can name every man, read every personnel file and then build up a story that is intensely personal. The Niue story is unique and at the same time it is universal…The Niue story is unique and at the same time it is universal. Small communities everywhere have their own personal and emotional connections to what was a massive clash of empires, an incredible loss of life.”

Pointer has not been taken in by the jingoism. The stark truth is that the Niuean’s deaths in Europe, even if from sickness and not from battle, were useless, nothing a dawn service can ennoble.

Niue and the Great War by Margaret Pointer (Otago University Press, $39.95) is available at Unity Books.