With higher energy prices making it harder for heavy industry to operate in New Zealand, Pattrick Smellie of BusinessDesk looks at how the market might adapt.

What does it say about the accelerating de-industrialisation of the New Zealand economy that Norwegian pulp and paper giant Norske Skog’s likely closure of its operations at Kawerau barely makes the news?

True, the announcement was obscured by the budget last Thursday. And unlike the Ports of Auckland’s announcement that its chief executive Tony Gibson was leaving, Norske Skog didn’t put out a press statement. It doesn’t even have a spokesperson in New Zealand.

Rather, it was left to the affected union to tell the world that 160 jobs that underpin the economy of the town of Kawerau now hang in the balance.

A consultation process has begun and once a company gets to that point, it’s rare to see a change of heart.

Part of the problem, of course, is that its primary product since it began production in 1955 has been newsprint for newspaper and magazine publishers. The precipitous decline in the size and circulation of newspapers everywhere is hardly news.

Perhaps the end of that line has been inevitable for a while. But there are other things a large pulp and paper mill can be retooled to make. That Norske Skog appears to be giving up on New Zealand, despite this country’s ready supply of wood fibre, suggests deeper issues.

The most obvious being blamed is the price of wholesale electricity.

High power prices are back

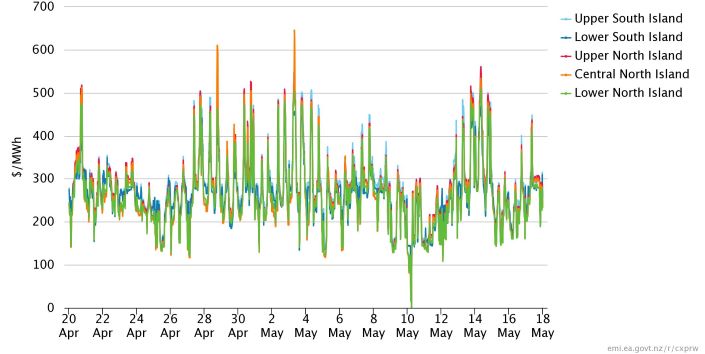

After a prolonged period in the middle of the last decade when wholesale prices were low and stable, electricity prices on the spot market have not only been very high, but also more volatile in the last couple of years.

The first few months of this year have been particularly punishing for some large electricity users.

Norske Skog could have avoided at least some of that pain by signing new contracts for supply at fixed prices. However, the company apparently chose not to, and has been cutting production and daytime shifts since earlier this year to avoid the highest power prices.

A generous person would say Norske Skog misjudged whether the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter would close and gambled last year on electricity spot prices falling once a smelter closure was confirmed.

Instead, the smelter’s majority owner, Rio Tinto, signed a deal with Meridian Energy that will keep the smelter running for another three years.

Power company executives, who say they were “begging” major electricity users to sign contracts at $90 per megawatt hour for power before Christmas last year, are now writing contracts at $175 per MWh.

Jarden analyst Grant Swanepoel told BusinessDesk last week that unless a large user was willing to take a contract for three years or longer, they could expect to pay $155-to-$165 per MWh for the foreseeable future on long term contracts.

For those riding the spot market, prices have regularly gone well above $300 per MWh in recent times.

A reasonable dollop of water streaming into the largest South Island hydro catchments since the beginning of May has eased fears of a classic “dry winter” leading to power shortages.

However, natural gas shortages caused mainly by production problems at the country’s biggest gas field, OMV-owned Pohokura, are expected to keep the electricity market tight and prices elevated well into next year.

Some scenarios suggest winter 2022 could be harder to manage if drier than average conditions persist through the coming spring and summer, while a Gas Industry Company discussion paper issued last Friday can see situations where natural gas shortages become critical as early as 2026.

If security of supply, price and environmental impact are the three guiding lights of energy supply, then the first two are looking shaky now and increasingly so by mid-decade.

Who cares?

Yet hardly any of this is making the news in the way that it used to.

Perhaps it’s that Covid-19 has sapped public interest in an old-hat issue. More likely, New Zealanders have got used to the idea that dry winters are manageable.

Most importantly, the government has chosen not to bite. This is a big relief in the executive suites of the major generator-retailers – Contact, Meridian, Mercury, Genesis, and Trustpower.

Notwithstanding the fact the wholesale electricity market has survived a bit more than 25 years, it has never been loved. Electricity generator-retailers remain as vigilant as ever for signs of regulatory intervention that could up-end their business models.

Keeping the issue live are small-scale electricity retailers, who cry foul whenever they are caught out by volatile spot prices.

Right now, however, there appears to be no political appetite to intervene. Megan Woods, the energy minister, has been quick to adopt the electricity generators’ line that big electricity users suffering high spot prices could have locked in lower prices if they’d chosen to.

She may not be a big fan of the electricity market, but there can be very little desire to open a new political front when the government is already struggling with a huge reform agenda, overlaid by the ongoing Covid containment challenge.

Glib though it may be, ministers might even claim as a win the fact New Zealand gets closer to its climate change emissions reductions targets when industries producing big greenhouse gas emissions close down.

The Onslow elephant

Instead, there are two emerging factors the power company executives might worry about more for the structure of their industry in the future.

The first is the apparent inevitability of the proposed Onslow pumped hydro scheme in Central Otago. The second is the likely need to reform wholesale electricity market arrangements anyway, to take account of a rising carbon price.

The Onslow scheme is widely panned by industry experts. They say it is likely to be so much more costly than its loosely costed $4 billion price tag that it will have to be abandoned. Or that it is unlikely to be consentable since it involves flooding a wetland. Or it may prove unbuildable because tunnelling through 15-to-20 kilometres of fragmented rock will prove impossible.

The most confident industry chiefs say it will never happen and will carry on building new renewable wind, geothermal and solar electricity plant.

However, if the Onslow project was built, it would be government-controlled and would give its operator the power to release stored water and bring power prices down at any time. The market would no longer be a market.

With a completion date for Onslow of no earlier than 2035, that is obviously not going to happen overnight, but it is giving ministers something to aim for.

Meanwhile, different factions in the industry are arguing the wholesale electricity market rules need to change anyway, based on the expectation carbon prices will rise and deliver renewables-only generators like Meridian a windfall gain in higher power prices.

This, rather than a sudden urge to change the electricity market in response in volatile spot prices or industrial site closures, may be where the greater danger lies for electricity generators that have spent a generation honing their sense of regulatory risk.

This article originally appeared on BusinessDesk. Their team publishes quality independent news, analysis and commentary on business, the economy and politics every day. Find out more.