Duncan Greive recently argued the case for a part sale of Kiwibank. Edward Miller gives us the counterargument.

The Commerce Commission market study on the banking sector wants to see Kiwibank become a “disruptor” to the four major retail banks, and has asked the government to consider how it can access more capital to do that. Chief executive Steve Jurkovich has stated that Kiwibank is up for the challenge.

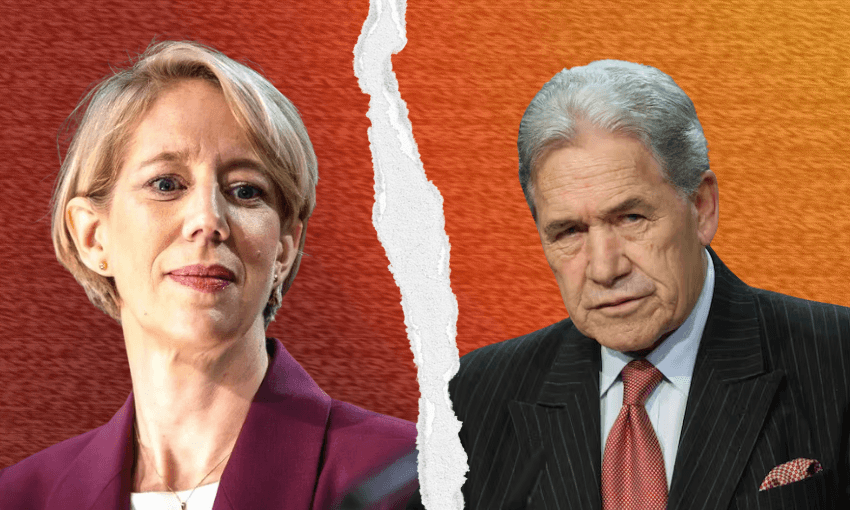

Excusing the Silicon Valley language of “disruption”, there seems to be widespread agreement on the need for capitalisation, but disagreement on how to achieve it. Government could capitalise it directly, but the minister of finance Nicola Willis has been preparing the ground for a share sale as the best approach.

One need only look at the crisis unfolding in the electricity sector in the past couple of weeks to get a sense of the problems with this approach. In the decade since the partial privatisation of Mighty River Power (now Mercury), Meridian and Genesis, the gentailers (the above three companies, plus fully privatised Contact) paid out $10.8 billion in dividends while generating capacity increased by a mere 1%.

From 2016 to 2020, gentailer dividends were paid out at more than four times the level of new investments in generating capacity. We are paying for this now, with surging electricity prices hammering households and destroying manufacturing employment.

It’s still early days, but what’s being hinted at for Kiwibank seems similar to gentailer privatisation, where the government retains a majority shareholding, but has limited scope to exercise that shareholding in “non-commercial” ways that support broader policy objectives. In the electricity sector, these objectives would include things like reducing energy costs or accelerating decarbonisation, while in the banking sector, we’re really talking about cheaper banking services.

That brings us back to ComCom’s market study, which was commissioned because New Zealanders were paying too much for banking services.

Everyone complains about the banks, right? Is New Zealand really out of step with the rest of the world?

The market study compared the profitability of NZ banks to a range of peer nations over the past decade. It found that NZ banks were higher than the upper quartile of that sample in terms of three core bank profitability measures: return on equity, return on assets and the net interest margin (see pages 158 to 164). In other words, our banks are about as expensive as anywhere in the developed world.

Shareholders of the Big Four banks have no doubt been appreciative of this status quo. We don’t yet have 2024 financial results, but 2023 was a record year for the Big Four, with pre-tax profits reaching $10 billion in 2023 for the first time.

And, while annual profits are rising, 2023 is right on brand for the Big Four. Over the past decade,their net profit after tax totaled $49.5 billion, with 77% of that – some $38.5 billion – transferred to their parent companies as dividends.

While Kiwibank is much smaller than the Big Four, its net profit after tax still came to $202 million in the 2024 financial year, a 15% jump on the previous year.

And, RBNZ data shows that its net interest margins – the key measure of profit in the sector – are right in line with the Big Four, and in the last couple of quarters have actually been a shade higher.

This is particularly interesting, given Kiwibank’s home lending book has grown 2.7 times as fast as the market in the past year. People want to bank with a NZ-owned bank. What if that was the cheaper option?

Capitalising Kiwibank

Nicola Willis has directed Treasury to engage with Kiwibank’s parent company on options for raising new capital, “including from KiwiSaver funds, New Zealand investment funds and investment from everyday New Zealanders.”

The Kiwisaver option appears to be the most benign approach, but there’s some history to consider here. Until 2022, some Kiwibank shares were held through the government’s ownership of the Super Fund, NZ Post and ACC, but the government had first right of refusal over any future sale.

The Super Fund was keen to purchase some or all of NZ Post’s share, but, as CEO Matt Whineray noted, “we sought the flexibility to introduce private sector capital … to preserve all options for exiting the investment in the future.” This is the first big problem: selling shares to pension funds might sound nice, but how do you stop them selling them on and then banking the capital gain?

According to Duncan Greive, it might be worth taking this risk because we need to find a way to fund the growing cost of superannuation, and there “are not a lot of significant New Zealand businesses for the Super Fund to invest into.”

I’m sympathetic to this problem, but relying on Kiwibank’s profits to fund superannuation seems to ignore the actual issue of the excessive costs of banking in this country. It will also likely do little to reduce those costs – instead of the Big Four, we might just end up with the Big Five. That’s unlikely to generate any real disruption in the industry.

Regardless of what Kiwisaver fund operators like Sam Stubbs say, fund managers wouldn’t be buying Kiwisaver shares solely because they want a more competitive banking sector. They want a return, and they have an obligation to maximise that return for their customers.

If we want Kiwibank to live up to ComCom’s disruptor dream, then it needs to do more than just match the prevailing returns in the market. It needs to beat them, and that means having lower interest margins than the Big Four.

Lower margins means lower mortgage rates, means Kiwibank winning a larger share of the national mortgage book, means other banks cutting their rates in response. This is competition. This is disruption. This is Kiwi?

But lower margins also mean lower returns for shareholders.

Private shareholders can’t settle for this so easily, but the state can, provided it meets other policy objectives such as lower-cost banking services and easier pathways to home ownership for struggling families.

Think of the government capitalising Kiwibank as capital investment in our national banking infrastructure. As with physical infrastructure, banking infrastructure makes our lives easier, lowering the barriers to economic activity.

On the balance sheet this probably means borrowing, which means a bit of debt servicing cost in the mix as well. Given the government can generally borrow more cheaply than the private sector, this doesn’t seem like a major barrier.

But there is a clear financial payoff to New Zealand families struggling with sizeable mortgage costs. It would reduce pressure on government too, which subsidises incomes through Working For Families and other income support measures.

Kiwibank was established in 2002 to prevent profits heading offshore to the Big Four Aussie-owned banks. Wouldn’t it be better if we ensured that all Kiwibank’s profits stay in New Zealanders’ pockets?