Controversial motorway project Penlink will join Whangaparāoa Peninsula to State Highway 1, but Stillwater residents say it will ruin their peace and quiet. Chris Schulz pays the small north Auckland settlement a visit.

Peter Wilson stands on his doorstep with his hands on his hips. “A quiet spot,” nods the retired mechanical engineer, gazing out over the Weiti River and across to the horizon. It’s overcast and drizzly, but finches fly over our heads, making it easy to see why Wilson and his wife Gina moved here from the UK in 2005 and never left. “The water’s still, the air’s still, you can hear the birds singing,” says Wilson, smiling. Then he sighs, his accent still evident, “Stillwater.”

About a half-hour drive north of Tāmaki Makaurau – if you know where you’re going – lies a small isolated settlement of around 600 homes and 1,500 people. You can’t jump on the motorway to get to Stillwater. Instead, you have to navigate suburban streets, then rural roads, to find Duck Creek Road, where you’ll be greeted by a bucket of chalk hanging from an old bike tyre and a blackboard that reads: “Happy Birthday Jayden”.

With no shops, churches, pubs or public transport, and just a members-only boat club and a community hall for entertainment, it’s a place where residents enjoy the quiet life. “If you live here you accept the fact that you live at the end of a road,” says Wilson. “There’s literally nothing.” He’s right: on the day The Spinoff visits, I encounter just three people across several hours. Wilson and Gina are two of them, the third a man walking his dog who waves to me.

People come here, and they stay here, for that lifestyle, says Wilson. “We’re near to the city in a nice quiet place … you’re in a different world.” That isolation has made Stillwater a sought-after location, with houses snapped up on the rare occasion they go on sale. The only downside is that noise from lawnmowers or chainsaws echoes around Stillwater’s basin-shaped location. “If a dog farts on the other side of the valley, we’ll hear it,” says Wilson. He’s right: only those birds and the hum of his fridge can be heard as we talk and take in his view. “We hear everything here.”

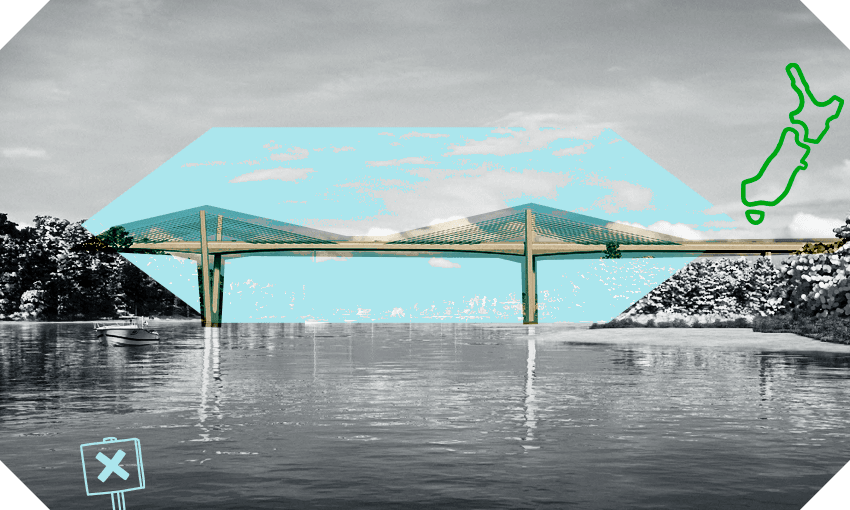

That peace and quiet is about to change. In a month’s time, work is scheduled to begin on a “massive” motorway project connecting Whangaparāoa Peninsula to State Highway 1, a $830 million motorway extension called Ō Mahurangi Penlink that will take four years to build. It’s a 7km stretch of road with room for pedestrians and cyclists that includes a bridge across the Weiti River just north of Stillwater, one that will stretch across Wilson’s horizon, ruining his views. Other residents are even closer to the project, with some just 100 metres away.

The toll road is needed because of the commuter traffic that backs up along Whangaparāoa Road and congests around Silverdale every weekday morning and evening, and often on weekends. One resident describes living there as “a nightmare”. Penlink is seen as the only option by those in authority to ease this congestion, and those living on the peninsula agree. “One lane in, one lane out – Penlink, bring it on,” a local told Newshub in 2018. “Sooner the better please!” said another.

The project has been mooted for decades as the cure to Whangaparāoa commuters’ ills, but never quite got over the line. The Auckland Business Chamber reports Penlink first being pitched as far back as 1981. Twenty years later, as a beginner journalist at the North Shore Times-Advertiser, it’s one of the first stories I wrote about. Wilson repeats a rumour he’s heard that it dates back even further to the 1950s as a post-war project, something The Spinoff couldn’t verify. Since 2000, it’s bounced between Rodney District Council, Auckland Council and Waka Kotahi, falling in and out of favour depending on which politicians were trying to champion it.

That means confusion surrounds Penlink’s backstory. Piecing together the facts is difficult. “There’s a massive history,” warns Peter Davy, chair of the Stillwater Community Association. Since he moved into the community five years ago, he’s kept busy trying to piece the past together, collecting a box of documents that he keeps in the boot of his car. “There’s so much confusion,” he says. “Things that may have been agreed on may have only been agreed verbally.” When I ask him if there are any cold, hard facts, Davy replies: “I can’t tell you what’s true and what’s not any more.”

One thing’s for certain: Penlink has been delayed for so long that no one in Stillwater ever thought it would be built. Wilson didn’t think so when he moved there in 2005. Davy didn’t think so either when he moved from Waiheke Island five years ago, but bought a house far enough away from the project that it wouldn’t affect him, just in case. Kevin Hawkins first sailed his boat into Stillwater in 1981 and has lived there since 2006. He never thought he’d see the day Penlink would get the go-ahead. “We vaguely knew a bridge would be built one day – but not really. It wasn’t in a hurry,” he says. “I’m quite surprised it’s happening. I see it as a bit of a folly.”

Like it or not, that “folly” is happening. “Ō Mahurangi Penlink is more than just a road, it is a vital connection for north Auckland, linking the Whangaparāoa Peninsula with the wider Auckland region,” said transport minister Michael Wood when he confirmed the project in June. “The road will not simply support the surrounding community through more lanes for cars, it will provide safer and more sustainable transport choices – becoming a key public transport route while also promoting walking and cycling on a separated shared path.”

HEB Construction, Fulton Hogan, Aurecon and Tonkin + Taylor have been confirmed as construction partners. Officials gathered together to sign a document and pose for this photo in June. There, Mana Whenua gifted the project the name Ō Mahurangi, “a reference to Mahurangi, a tohunga (priestess) who lived in Hawaiiki and whose powers are said to have enabled the construction of the great voyaging waka Tainui”. A press release boasted that Penlink would “enhance the lives of those living and working in these growing communities”.

But Wilson says nothing about the project enhances what they have in Stillwater. Across the four years that he fronted the residents and ratepayers’ association, Wilson appeared at countless meetings representing a common Stillwater attitude: don’t build Penlink. His reasons are numerous: the four-year construction noise, the damage heavy vehicles will cause to Duck Creek Road, the impact on wildlife and waterways, the dust that will infiltrate residents’ rainwater tanks, and the traffic noise once it’s finished. “They’ve looked at this and decided, ‘We’ll put a brand new road right through virgin forest. We’ll put a 7km road in and by the way, we need to build a bridge over the river. Yeah, that’ll be fine. That won’t inconvenience anybody.'”

Selfishly, Wilson admits he also doesn’t want a motorway marring his views, and those of his son, who lives next door with his family. “They’re making their omelettes from our eggs,” says Wilson. “We’re the ones who have to suffer … It will totally destroy what we have here.” Now it’s going ahead, Wilson says even more residents are voicing concerns. “All the people who were naysayers, [who said] ‘It will never happen, I’m not going to worry about it’, have become, ‘It is going to happen, now I’m worried about it’.”

No one denies that something needs to be done to ease the shocking traffic congestion experienced by the 30,000 people who call the Whangaparāoa Peninsula home. “It’s mental,” says Jennifer Mann, who describes peak traffic as “God-awful”. The marketing manager for Max recently moved from Ōrewa to Red Beach, one of the closest suburbs to State Highway One. But even she’s getting up earlier every day to get into work in Auckland city, an hour-long commute. “If you leave any later than 6.30am it just completely changes the drive time into the city,” she says.

People want to live there because of the lifestyle, and have access to a range of beautiful sandy beaches. But if Mann lived any further down the peninsula, she says she wouldn’t bother trying to get into the city. “I wouldn’t be working where I work, I can tell you that,” she says. “It would be a nightmare.” Penlink, she says, won’t work for her because she’s too far from the access point. Instead, she hopes it eases traffic levels through Silverdale, where four sets of traffic lights also help cars coagulate. “I have friends who have purchased on the coast and [Penlink] is definitely something they’re hanging out for because it’s going to be such a drawcard to be able to get somewhere faster,” she says. “I can see the benefits.”

Waka Kotahi say Penlink will halve the amount of traffic along Whangaparāoa Road. Wilson isn’t so hard-headed that he won’t use Penlink. The project includes a motorway interchange so Stillwater residents have easy access to State Highway One or Whangaparāoa. Yes, they’ll be tolled – somewhere between $1 to $4, depending on who you ask. But, even now, one month out from construction starting, he questions whether it needs to be built at all. “The key issue is getting through Silverdale,” he says. “That’s where the hold-up is.”

He suggests a dedicated free-flowing road bypassing Silverdale could have been built years ago at a fraction of the cost. It’s something he hammered home time and again at all those meetings, using his problem-solving background as a mechanical engineer. “If you’ve got a blockage in your pipe, you don’t put another pipe in,” he says. “You sort the blockage out.”

Clearly, Wilson’s views are too late to make a difference. Davy agrees that many Stillwater residents feel resigned to a motorway becoming a permanent fixture of their isolated community. “Most people I’ve spoken to recently realise it’s going ahead. It’s nothing they can stop,” he says. “It’s more about shaping it to be as good an outcome for the community as possible.”

Noise is shaping as the deciding factor. Waka Kotahi says mitigation factors, including road sealants and a speed limit of 80 km/h, will help curb traffic noise affecting nearby residents. “Managing the impacts of construction, including noise, light pollution etc, on neighbouring communities was a key consideration during the tender process,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “The alliance chosen to construct Penlink demonstrated superior understanding of minimising impacts through design-based solutions.”

But Peter Jordan, a third “Peter” interviewed for this story who lives in Stillwater, is sceptical about whether that will work. “A number of motorbikes and cars generate excessive exhaust noise, and this noise can only be mitigated by noise barriers,” he says. “Noise barriers are not proposed.” Once Penlink’s finished in 2026, Wilson says he’ll set up noise-measuring equipment up on his deck to make sure the project sticks to strict decibel limits.

But Penlink isn’t the only big project planned to interrupt Stillwater’s quiet life. Auckland’s obsession with building townhouses has reached the small settlement, with up to 12 of them planned for the site where a motor camp currently sits. “The development of that is kicking off, so I’ve been told,” says Davy. “Residents have been given 12 months to vacate.” Clearly, after 40 years of umming and ahhing, big city life is finally coming to Stillwater whether those who live there like it or not.