If you thought this week’s damning report on the state of our supermarkets would augur big changes in the sector, brace yourself for disappointment.

This column was first published on Bernard Hickey’s newsletter, The Kākā.

The Commerce Commission’s scathing draft review of the Foodstuffs/Woolworths duopoly suggests state intervention that could include a new ‘Kiwishop’ chain and/or a Telecom-style break-up. But don’t bet on either actually happening.

Telecom was a locally-listed and a former state-owned network monopoly that could be relatively easily broken in two with legislation, a share split and a couple of minor regulatory tweaks. The two supermarket chains, on the other hand, have ownership structures (two cooperatives with individually owned supermarkets, and an Australian-owned corporate) that mean they would both be fiendishly complicated to unravel.

Breaking up Foodstuffs and Woolworths and creating a state-owned ‘KiwiShop’ competitor – a sort of Vodafone vs Spark vs Two Degrees model – would be like trying to unravel a bundle of 2,000 phone charging cords after digging them up from the bottom of a landfill.

I’m tired just thinking about a separation

Just imagine having to disestablish Foodstuffs’ two cooperatives, which are owned by multiple family trusts in an opaque series of supply agreements, lease agreements, warehouses, logistics operations and stores that would be bone-achingly difficult to understand, let alone pick apart. Rebuilding the web of relationships between individual store owners and suppliers (because Foodstuffs allows store owners to deal direct with suppliers) would be a nightmare. Woolworths’ Countdown would be easier, given its more centralised structure, but it would require some sort of pseudo-nationalisation of a major foreign-owned asset. This would not please our Australian friends either.

That’s not to say there is no problem and we should all just move along and suck it up. The 517-page full report is a detailed, meticulous and cracking read. Even the 22-page (!) executive summary is well worth a look. For slackers, the media release is damning enough on its own.

What a successful duopoly looks like

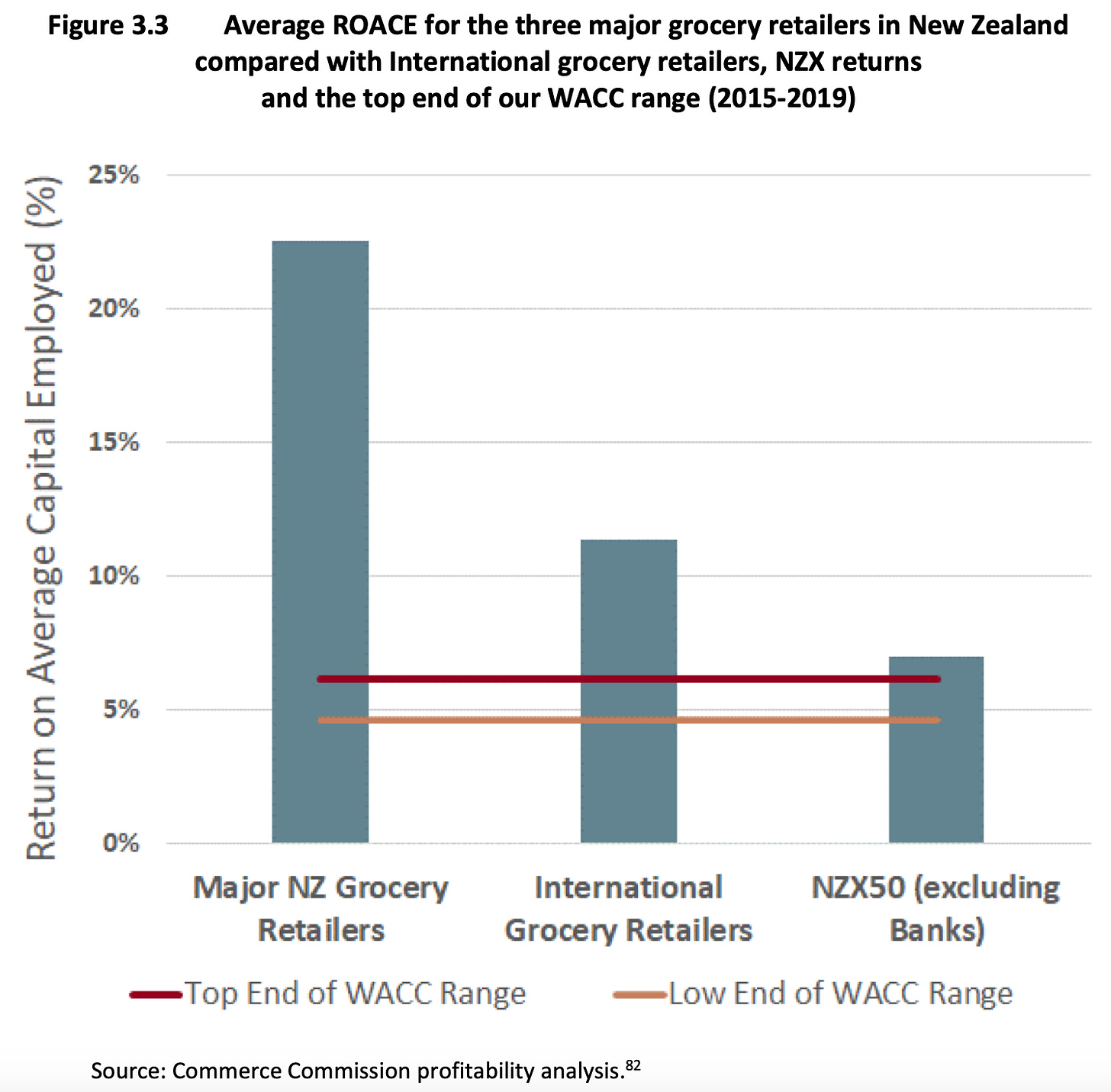

Here are the charts from the report that tell you everything you need to know. The duopoly generates returns on average capital employed (ROACE) that are at least three times as high as supermarkets in other markets, three times their weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and twice as high as NZX-listed company returns, which is no mean feat, given the NZX list includes electricity companies, Z Energy and the retirement home groups.

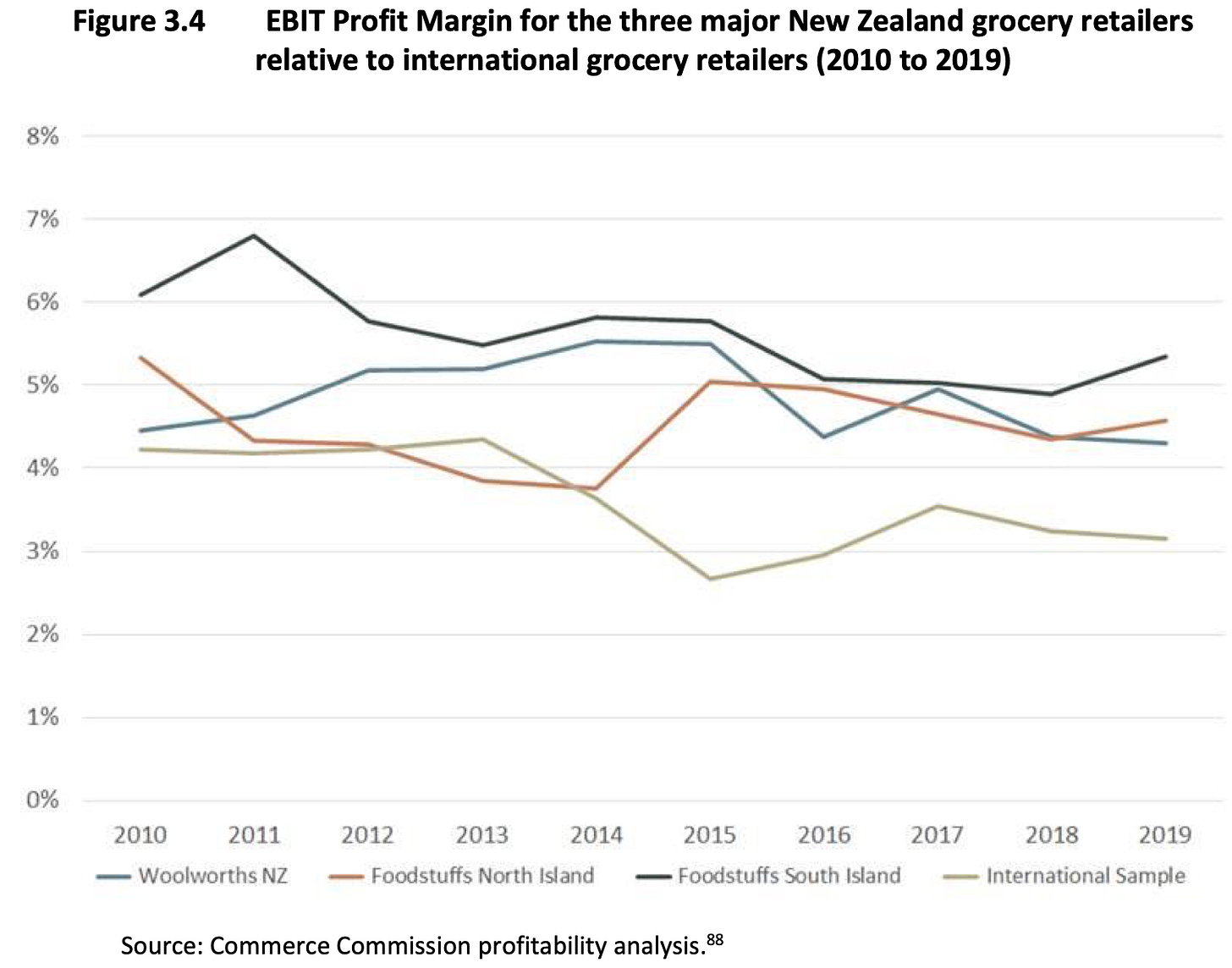

On another measure, the earnings before interest and tax (EBIT), the supermarkets here have profit margins that are around double their international peers. Foodstuffs South Island’s profitability is particularly wonderful or egregious, depending on your point of view.

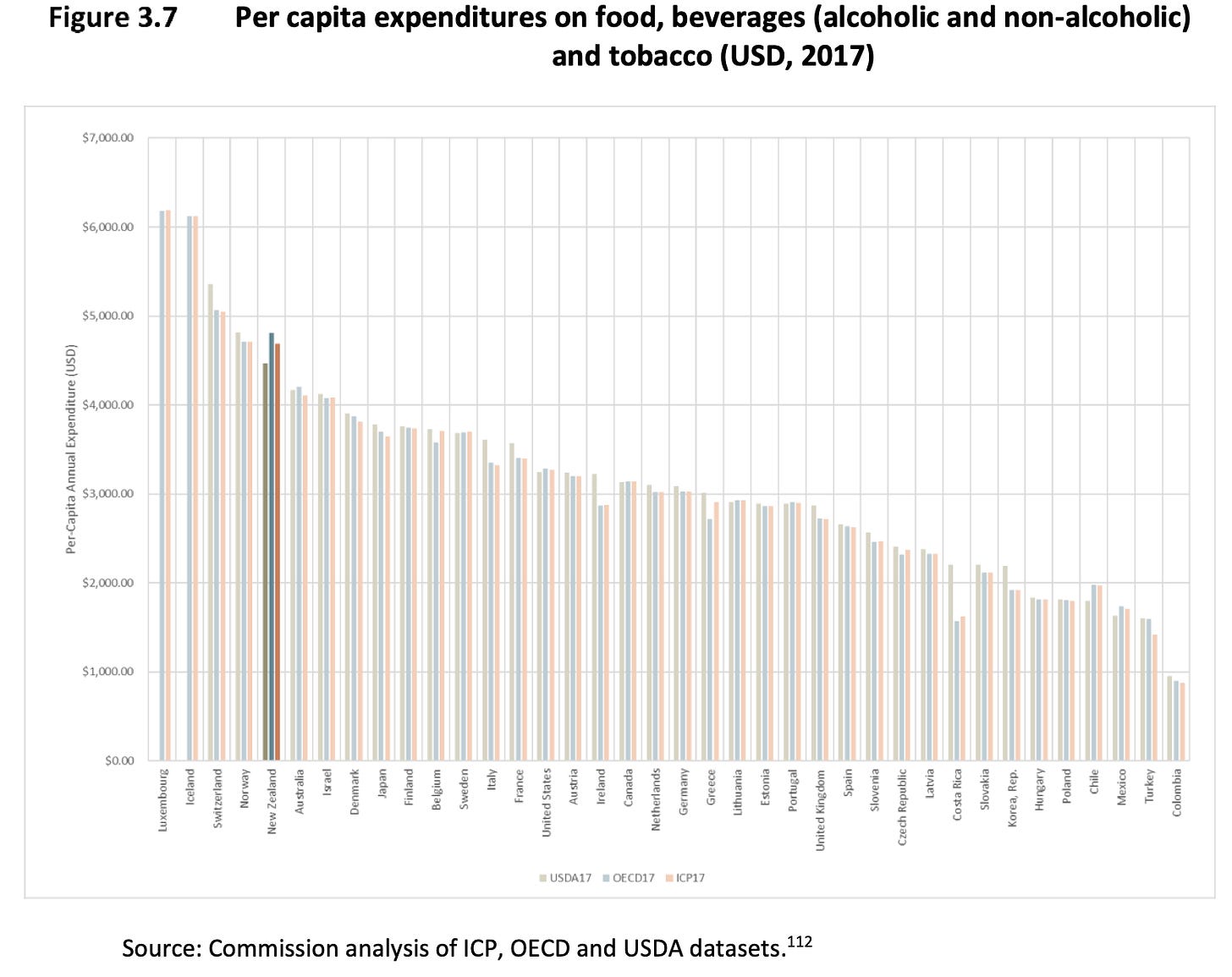

All that means New Zealanders spend the fourth-most per capita on groceries in the world, behind hyper-rich countries and luxury tax havens such as Luxembourg, Iceland, Switzerland and Norway. Add on the oligopolies of banking and electricity and the most expensive housing and rental markets in the world, and consumers and renters can feel particularly aggrieved.

So what should or could the government do?

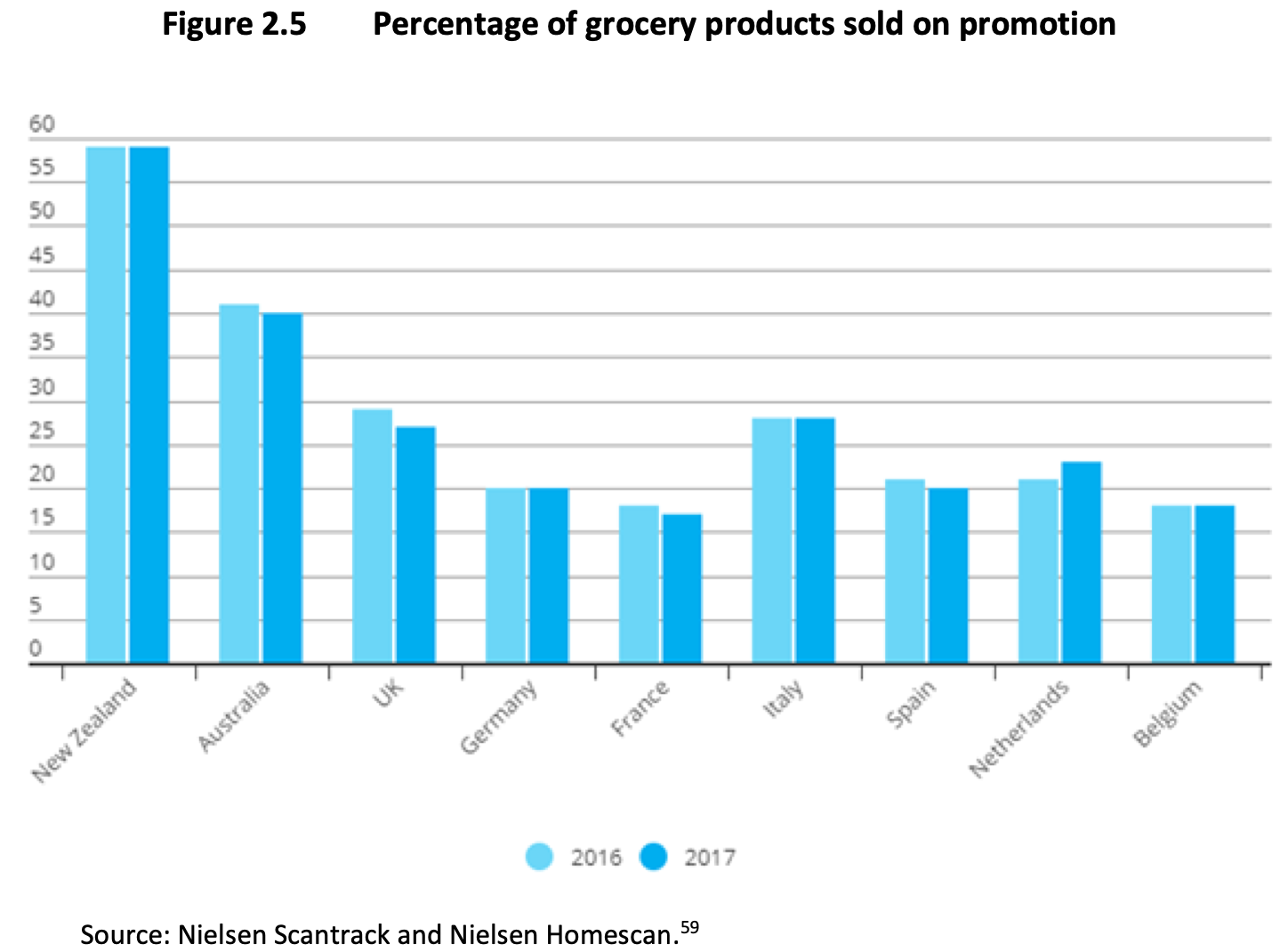

The government could legitimately beef up the prosecution arms of the Commerce Commission and other regulators to crack down on the no doubt rife abuse of the Fair Trading Act and the Employment Relations Act. It could also serially harass the two chains, particularly Foodstuffs, into paying its workers better and stamping out any migrant abuse, along with exposing the “confusion marketing” implicit in their promotions and loyalty card schemes. This chart I call the “Who are they kidding” chart.

The government could also create vehicles for aggrieved suppliers to safely embarrass the hell out of the supermarket chains over the repeated bullying allegations.

Sadly, it will also be difficult to help a freer market solve this problem with regulatory tweaks and interventions. The Commerce Commission was able to force through number portability and slash termination rates in a way that unleashed real competition in the mobile phone sector. The National-led government was able to subsidise the mass rollout of broadband fibre to beef up Chorus’ publicly accessible (wholesale) backbone network to encourage a flowering of fixed-line competition. That is not as possible in the groceries markets, where thousands of different products are delivered and sold in thousands of different ways at even more thousands of different prices.

The government could help the likes of Costco (which is building one big store in West Auckland) and Aldi to establish bases in a couple of big cities, probably Auckland and Christchurch, to provide at least some competition. They may need accelerated RMA help for sites or overseas investment exemptions, which should be expedited. But establishing the sorts of deeply networked chains with hundreds of local presences would be too difficult, expensive and time consuming a task for the government to undertake.

Unfortunately, the interventions seen in fuel retailing after the first study will be difficult to replicate. In fuel retail there are relatively few product types, few distribution points (ship terminals and pipelines), and the potential for smaller competitors to make a big impact. Waitomo, Gull and NPD have kept the big fuel companies increasingly honest in the last couple of years as they finally got their automated sites up and running on the fringes of the big cities.

However, the challenges inherent in the supermarket sector shouldn’t stop the government considering this sort of “breakup and state-owned competition” strategy in other markets where the demarcation lines are much clearer. It has some big irons in the fire already: the power industry is one. Banking is another. The supermarkets duopoly may survive this increased scrutiny, but other industry players may not be so lucky.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.