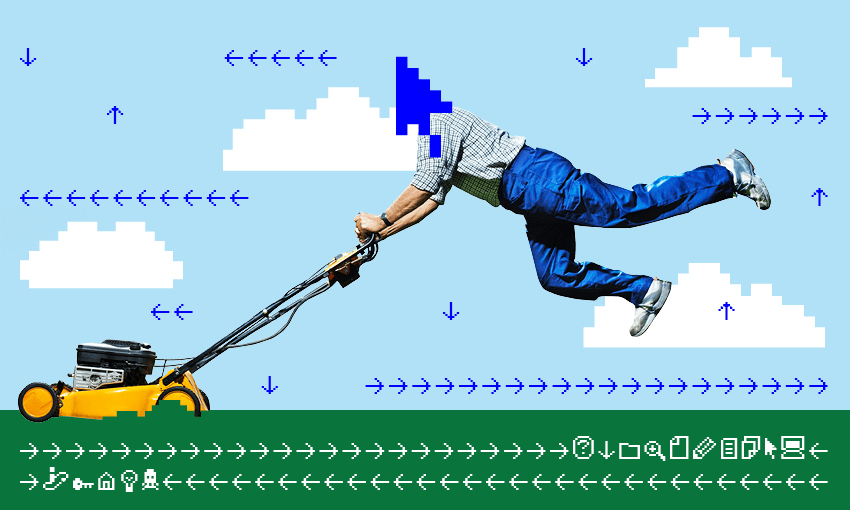

Gamers are flocking to lawn mowing, truck driving and house cleaning simulators. For IRL, Josie Adams discovers the appeal of mundane games.

Every day, Emma Maguire goes to work as a communications professional in Wellington. Every night, she drives a truck through Europe. She bought her truck simulator for $2 on Steam, a game-purchasing platform, a few years ago. She’s never looked back. While hiking and dancing are tools she’s used to de-stress physically, she now has the option to check out of her brain almost completely. “I find driving a truck is more chill [than hiking]. You don’t have to move.”

Maguire is one of a slowly-growing number of people who are opting for “mindless” simulator games; games like Lawn Mowing Simulator, where you drive a ride-on lawn mower, or Powerwash, where you clean houses. Euro Truck Simulator 2 has sold more than nine million copies. What paint-by-numbers is to visual art or First Dates is to television; that’s what these simulators are to gaming. These games, which simulate mundane tasks or everyday jobs, are described by users as meditative and soothing. “You just sit there and drive for two hours and listen to podcasts,” said Maguire.

Would Maguire like to drive a truck in real life? “Absolutely not,” she said. In real life she cannot drive a car, let alone a truck.

While spending your night driving a virtual truck might seem strange, this kind of game has a long-established history. In 1979, the first Flight Simulator game was released. A reviewer called it “the single most impressive computer game” they’d ever seen: “The German fighter pilot capabilities range from OK to very good and seeing them stacked over their field was almost a physical pleasure.”

In Airplane Mode, released last year, there are no German enemies.There is Sudoku, a nice window view, and a call button to order drinks. The simulation is for passengers, not pilots.

The gaming dream is often extreme: even in the early days, games like Battlezone and Bad Street Brawler were designed to make players feel ultra-accomplished and badass. Today’s games, like Halo and Fortnite, imbue players with cool powers and gear and dump them in strange new worlds. It’s easy to see how simulations like Euro Truck Driver could be the antithesis of gaming culture, but they may just represent an evolution of it.

Lee*, who is keeping his last name a secret so as not to be embarrassed in front of his workmates, plays Snowrunner. This is another truck simulator, but with snow. He’d never been a “simulator person” until he downloaded the game six months ago. “I stopped playing all other games when I started playing it,” he said. “I’m now watching Farming Simulator videos.”

He said that after a long day at work – he’s a UX designer for an Auckland software company – he likes to put on some Four Tet and drive around the icy roads of Michigan: “You put music on and stare at trucks for a while.” Lee has a self-imposed set of restrictions, and refuses to leave Michigan until he’s completed all the tasks nearby.

Why all the meditative virtual driving? Are Lee and Maguire more stressed than the rest of us? The answer, they both reckon, is no. They’ve just got a different outlet; one more and more of us are discovering.

Victoria University senior lecturer Dr Simon McCallum, an expert in gaming development, said simulator games aren’t just about doing virtual chores; they’re about doing chores slightly more easily. “Power washing is an amplification of your power over hand washing things,” he said. In a simulation you do these apparently mundane tasks more easily, and without any complicated decision-making. “In a complex world, where we have lots of challenging interactions, sometimes people seek out simple things.”

He compares the appeal of simulator games to the Scandinavian-inspired slow TV movement. “My wife stayed up and watched the sheep-to-jumper television programme,” he said. “They were going for the world record for how quickly you can go from wool on a sheep to a fully done jersey.” It’s fast for a jumper, but slow for TV; and that’s what we crave.

He said a big benefit of slow TV is that we don’t have to activate our executive function so much. “You’re not having to make choices. You’re not having to negotiate. You’re not having to socialise. You’re not having to keep up with a complex plot,” he said. “I think the complexity of our world and the stress in our world may mean that we are wanting more of that than we have in the past.”

On the other hand Tom Walker, an Australian comedian, has worked hard to complicate his truck driving. He has more than eight and a half thousand followers on his Twitch channel, where he live streams his American Truck Simulator sessions. He started streaming when the comedy circuit got shut down by the Covid-19 pandemic. “I needed something to do and a job, probably in that order,” he told The Spinoff. “I started truck streaming because it was low impact enough that I could just natter on to the chat.”

On Twitch, viewers can donate money in exchange for a moment of game control, or a fun performance by the streamer. Walker set up a couple of options: for $5 you can yank the wheel of his truck left and right. For $13.37 he enters “Wig Mode”, and wears his girlfriend’s blonde wig for 20 minutes.

While he mostly streams for money, he also does it for love. “My audience are smart and funny and I appreciate them too, not just for the financial aspect,” he said. “There are genuinely people in the chat who I look forward to seeing.”

While players like Lee and Maguire are more casual, Walker takes the simulations at an expert level. He used to be like them, taking long-distance contracts and driving for hours using the keyboard. “It was relaxing and low-stakes and felt like I was just zooming along the road, able to not think about anything,” he remembered. “I didn’t know a Scania from a Volvo.

“Now I’m a freak with a steering wheel, pedals and an H-pattern shifter that plugs into my big computer and I can spend minutes trying to get a park right.”

Oskar Howell is a “gamer advocate” and ex-gaming reporter. He knows even the most boring simulators can be made extreme. His simulator of choice, Farming Simulator, has been turned into a full-on esport – the elevation of a game to the level of a professional sport – by its fans. “Players will strategically ban or pick vehicles to make the lives of their opponents difficult, then spend 20 minutes in a low-octane esports environment where they rush around delivering hay bales,” he said. “It’s bizarre, but I can’t fault it.”

Howell said real-world simulators have always been “something of an oddity” in the gaming community. “Why would the average person devote their time to a career that they could pursue in the real world?” he asked. “I spend most of my time playing in virtual worlds I’d never want to experience in real life, like warzones or fantasy worlds.”

That being said, he absolutely froths the virtual farm. Like the other gamers we spoke to, he finds mindless simulations soothing. “People want the occasional detox from the high-intensity life of shooters and racers, and if that means driving around a virtual combine harvester, so be it.”

During the Christmas break, Howell played 100 hours of Skyrim over 17 days. Sometimes he’d take a night off to play Farming Simulator as a “break”. “If I played Counter-Strike: Global Offensive [a competitive shooting game] for a solid month of grinding, I might expect to need a night or two of something slower-paced like a Farming Simulator to detox and reinvigorate,” he said.

This is the core of the simulation evolution: we play them to rest. Just like in Airplane Mode, we’ve become passengers in the game, not pilots. Lee used to fly planes, and used the older flight simulators to enhance his learning for a pilot’s license. Truck simulators, he said, don’t work the same way: “It’s not like [Flight Simulator], you’re pretty much in a truck with some hairy arms that go left and right, and then you fall off a cliff.”

While Lee doesn’t feel modern simulators have the same extreme environments as older games, the stakes are still higher than in real life. “My God, if trucks went over [in real life] the way trucks go over in Snowrunner, we’d be in a very poor place.”

McCallum believes there’s a dual appeal in simulator games: like slow TV, they require very little brainpower. But like traditional games, they also give us a sense of accomplishment. “You’re motivated because you’re wanting to see completion, and you want to have the right level of agency in the world,” he said.

“One of the nice things about Lawn Mowing Simulator is that when you’re done, the lawn stays mowed.”