We did not feel those good vibrations, nor taste any sweet sensations.

The kūmara fries are bland, tasteless and come not with aioli but tomato sauce. The thickshakes include chocolate buttons that need to be rescued from their milky grave with fingers. The burgers are not of the smashed variety, instead made with stale buns and undercooked patties. Mine was thick and chewy. Possibly like barnacle meat.

During a midday mid-week service, during which surplus staff at this kitted-out celebrity burger joint on Auckland’s waterfront seem to be standing around with nothing better to do than watch the many screens showing sports, the waiter still screwed up my order. It was a lifeless, listless, soggy, sad burger experience.

Should I go on? At Wahlburgers, New Zealand’s first taste of the global burger chain owned by movie star “Marky” Mark Wahlberg and his New Kids on the Block-rocking brother Donnie, the vibe is way off. In Euro’s old spot on Princes Wharf, its Woolworths-aping logo and clear glass frontage gives it the sterile appearance of a chemist, its plastic green chairs invoking the experience of a cheap St Patrick’s Day party.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. The arrival of New Zealand’s first Wahlburgers was covered breathlessly by media as its opening was delayed and delayed again, before Wahlberg stepped in to hype it up himself. “I cannot wait to come and join you for a cold WahlBrewski beer and a Kiwi-style burger with fried egg and a slice of beetroot,” he told fans in a Facebook video filmed from his personal home gym.

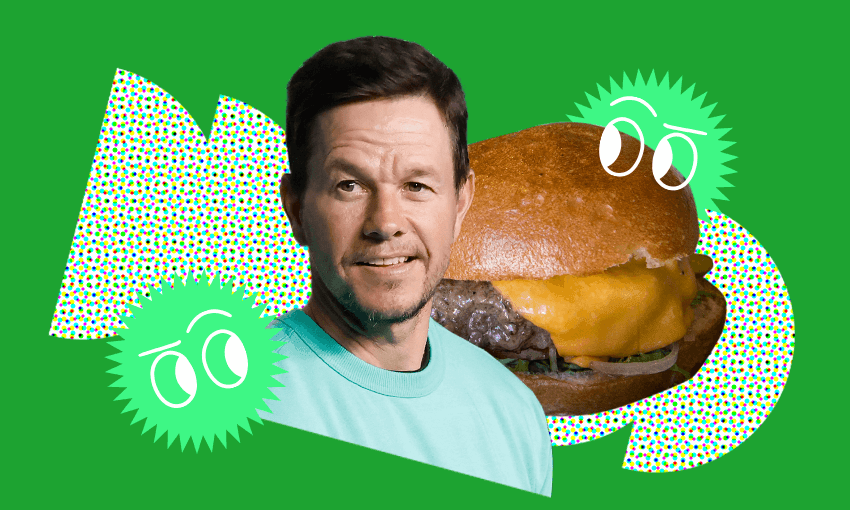

Perhaps that’s the problem. Wahlberg has the chiselled six-pack and movie star biceps of someone who rarely eats cheeseburgers or sinks WahlBrewskis. A quick Google search provides zero evidence of Wahlberg ever actually eating a burger. The closest is this snap in which the 51-year-old looks like he’s trying desperately to not even smell his burger, let alone consume it.

What you can find online is plenty of proof of Wahlberg’s intense daily workout routines and diets. They involve 3am starts followed by hours of cardio and weightlifting. Turkey, chicken and eggs feature heavily in his accompanying meals. Cheeseburgers, chocolate thickshakes, deep fried pickles and fries – a typical sample of a Wahlburgers menu – do not.

Since it opened in March, Wahlburgers reviews have sat somewhere between mixed and poor. “Burgers are average,” declared Emma on Google. “The loaded fries were soggy and lukewarm,” said AK. “I’ve cooked better burgers at home,” claimed a clearly disappointed Bryan. “Over priced bad food … $20 bucks of nothingness,” Wu agreed.

Even the critic from Stuff, which published at least six stories about the impending arrival of Wahlburgers, was unimpressed by the food. “Pretty standard … it didn’t blow my mind, and didn’t justify the $23 price tag,” they wrote about their Aotea burger, the one with beetroot and an egg. Others have experienced long waits. “It is about 1 hour waiting for the food. If you are [in a] rush or with [a] hungry kid, don’t come here,” warned Lux.

Timing is not the problem on the day I visit. Approximately four minutes after I place my order – an Impossible burger ($22), sweet potato fries ($7) and a chocolate shake ($10) – my drink arrives complete with chocolate buttons that are only edible if I use my fingers to scoop them out. (For the record, I was dining alone and was not game enough to do this). A plate of potato chips follows, which I did not order, and is soon replaced by kūmara fries, which I did.

Then the burger landed in front of me. It looked like this.

It tasted how it looked: tired. The watery Big Mac-style Wahl Sauce oozed everywhere, there were way too many onions, the tomato and lettuce were wilting and the patty was lukewarm and undercooked. The bun was the worst thing about it. It looked stale and was about as useful as a sieve. Soon, sauce, lettuce and soggy bun lay scattered across my plate, daring me to finish it. I could not. Like Bryan, I have also made better burgers at home for far less than $22.

As I left, I realised Wahlberg had been looming over me the entire time, a huge photo of his face beaming out the front door and across outdoor diners. More Wahlburgers restaurants are coming, threatening to spread to Tauranga and Queenstown next. Wahlberg himself will be here when his tequila bar opens up next door, the waiter tells me as I pay $32 – they discounted the fries after mucking them up – for my disappointing lunch.

Afterwards, as I walked through Commercial Bay, a busker on a trumpet played the “wa-wa-waah-waaaah” noise usually associated with epic fails. It felt entirely appropriate. Sorry Marky Mark, this was not a funky lunch I’d like to remember.