Cheese on toast is a humble classic, and cultures the world over have given it their own twist. In Mumbai, Perzen Patel grew up with the Indo-Chinese version, with optional (hidden) fried egg. Here’s how to make it at home.

As a kid living in Mumbai in the late 90s there were only types of restaurants to choose from – Indian, Chinese or continental. For the people who couldn’t choose, like my family, there was the local restaurant Solitaire, which had a 12-page menu and served everything from tandoori chicken to sesame prawn toast to pepper steak.

I didn’t know about dim sum back then. Or, the difference between Sichuan and Cantonese food. If it had chillies, spring onion or soy sauce in it, I assumed it was Chinese. Like Schezwan fried rice and hot and sour soup. Turns out both of those dishes were Indo-Chinese, a whole sub-cuisine that’s very hard to find in New Zealand.

Another popular Indo-Chinese dish was chilli cheese toast.

My working theory is that chilli cheese toast was born from sesame prawn toast, but some Hindu vegetarian decided that they’d skip the prawns altogether and the sesame too. It was available not just at vegetarian Chinese restaurants but also at gymkhanas, continental restaurants, Bombay’s Irani cafes and curiously, at my Gujarati neighbour’s house.

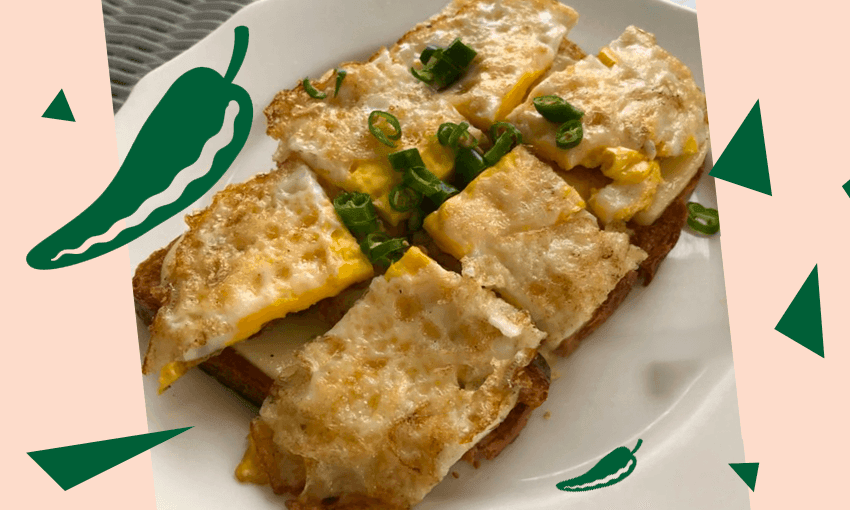

You can have chilli cheese toast by itself or topped with a sunny-side-up fried egg.

If you do the latter, then you’ve left China altogether and you’re now eating eggs Kejriwal, a dish created in the early 50s at Bombay’s Willingdon Sports Club for the rich Hindu merchant Devi Prasad Kejriwal. Rumour has it that he loved eggs but couldn’t eat them in his Hindu home. The chefs at Willingdon hid the eggs under a pile of cheese lest someone saw him.

CHILLI CHEESE TOAST

Serves 2

- generous helping of butter

- ¼ teaspoon garlic paste

- ¼ teaspoon ginger paste

- salt to taste

- crushed black pepper

- handful of mint, finely chopped

- 2 spring onions, finely chopped

- 1 green chilli, finely chopped

- 2 slices white bread (toast thickness)

- 100-150g grated cheese (the more the better)

- tomato sauce on the side

Optional: - 1 tablespoon ghee

- pinch of salt

- 2 eggs

Preheat your oven to 200C.

Soften the butter in a microwave. Add in the garlic paste, ginger paste, salt, pepper, mint, spring onions and green chilli. Mix together.

Heat a small frying pan and fry one side of the bread until it is golden and almost crispy.

Remove the bread from the pan and cut the toast into two triangles.

On the opposite non-crispy side, slather on a thick layer of the butter mixture.

Top with a generous mound of cheese. Bake the toasts in the preheated oven for about 5 minutes or until they become crispy.

Serve as is, or while the bread is grilling, heat a little ghee in a frying pan over a medium-high heat. Crack in the eggs, top with a pinch of salt and fry for 2-3 minutes until the whites are just set and the yolks are still runny.

Put the eggs on top of the toasts. Top it up with another mound of cheese and then grill for another minute. Serve immediately with tomato sauce.