Some people say it’s confusing. Others think it’s boring. But running all its elections under an STV system could be the single most effective way for local government to fix its lack of diversity and woeful voting turnout, argues Hayden Donnell.

The Spinoff local election coverage is made possible thanks to The Spinoff Members. For more about becoming a member and supporting The Spinoff’s journalism click here.

Turnout in our local government elections could charitably be described as catastrophic. Only 43% of eligible voters sent in a ballot in 2016. That figure was dragged down by a democracy deficit in Auckland, where just 38.5% of eligible voters took part. Seven Sharp’s average nightly audience is more than double the number of people that voted Phil Goff in as Auckland mayor.

When you drill down into the figures, things only get more depressing. Turnout was 89% among voters aged 70 or more, and only 34% among voters aged 18 to 29. Unsurprisingly, those distorted figures have led to local government becoming an electoral Alamo manned by an army of old white people.

The extent of the problem was detailed by Stuff journalist Charlie Mitchell earlier this month, in a story revealing New Zealand has more councillors named John than councillors born after 1980. Only 10% of elected members are Māori, while a woeful 3% are Pasifika and 1.5% are Asian.

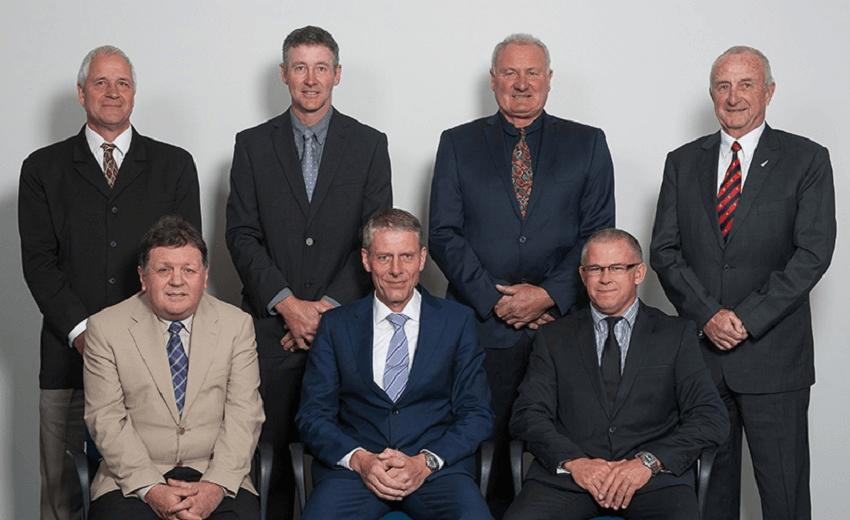

If those stats are already making you consider committing seppuku over your voting papers, don’t look at this picture of the West Coast Regional Council, which has a populace less diverse than your average men’s toilet.

Nor should you look at the Western Bay of Plenty District Council, which would call the police if it saw a young person nearby.

Unsurprisingly, recent research by the youth charity Seed Waikato reveals that only 5% of people aged 15-35 feel listened to by local government, and that 80% of young people feel disconnected from local councils. Most of the solutions to these problems are difficult and long-term. But one is obvious, and already in use in places like Porirua, Wellington, and Dunedin. If we want to correct our appalling representation statistics and combat voter disengagement, we should start by switching all our local elections to STV voting.

Otago University politics professor Janine Hayward is fed up. She tried to stay neutral on the topic of switching elections to Single Transferable Vote (STV) for years before her exasperation with our current system boiled over. “It’s just facts,” she says. “There are no political scientists that I’ve ever known who disagree with this idea. The problem is it’s just not an issue that ignites people’s imagination so it’s really hard to get them to change it of their own volition.”

At the moment nearly all of our local elections are run via First Past the Post (FPP) voting, while our District Health Board elections are legislatively required to be carried out by STV. Under FPP, you put a tick next to the candidates of your choice. Those who end up with the most ticks get elected.

In theory, that sounds simple. In practice it means the largest single bloc of voters can elect all the candidates they want, regardless of whether that reflects the will of the majority. Winning FPP candidates routinely get between 30 and 40% of the total vote. Often the majority of ballots are discarded, allowing committed cohorts of older, conservative voters to control elections even from a minority position. That’s bad in mayoral races and even worse in wards, where the same ideologically homogeneous groups can often vote in up to three candidates to represent them. In that sense, FPP is the system for people who believe National “won” the last general election with 44% of the vote.

“To put it crudely, you have a group who’s like a bloc vote [for] candidates who most often tend to look Pākehā, middle-aged and male, and they will elect those candidates from a list,” Hayward says. “And it effectively means that group is over-represented at the expense of what can be the majority of the population, which is completely not represented at all.”

STV removes those problems firstly by only giving people one vote. Instead of allowing voters to tick two or three candidates, it employs a ranking system. If your top-ranked candidate has either more votes than they need, or too few to get elected, your vote will keep moving down your list until it settles on a candidate who does require your vote to get elected. Think of John Key’s flag referendum for reference. If your first choice (Red Peak) got eliminated, your vote transferred to your second choice (Laser Kiwi), and third choice (a picture of a dog turd), and so on until one of your choices (Kyle Lockwood’s blue flag) was chosen*.

That makes it all but impossible for the largest group of voters to essentially elect three candidates to represent them, while everyone else’s vote is discarded. Last election under an STV system in Dunedin, 94% of votes ended up helping a candidate get elected. “So if you go back to that bloc of of voters, they’ll get a candidate elected for them,” Hayward says. “Say they’re about 30% of the vote. They’re going to elect one person. Then their votes are set aside and the rest of the voting community goes on amongst those vote transfers to determine who candidates two and three will be. It essentially means when you step back and look at who gets elected, it reflects – broadly speaking – the preferences of the whole of the voting community.”

That has a flow-on effect on representation. STV’s ability to better reflect the will of the entire voting population means it’s more likely to produce councils that look like the communities they represent. Research by Hayward and Professor Jack Vowles shows more women were elected under STV voting systems in the 2013 elections.

Adopting the system loosens the stranglehold older, mostly conservative voters have on democracy. It allows other candidates who are better-liked by the majority of voters, but who aren’t backed by a large, ideologically homogeneous group, to win office. Take the 2010 election of Wellington mayor Celia Wade-Brown as a case study. Her opponent, incumbent mayor Kerry Prendergast, won the largest share of first-choice votes, but Wade-Brown took the race because she won far more lower preference votes. “So if you’d asked the whole of Wellington’s population ‘put your hands up if you want the incumbent’, and if you want the other if it’s a run-off between the two of them, the majority would put their hands up for Wade-Brown, and that’s how she got elected,” Hayward says.

Because STV votes transfer once your first choice is eliminated, it also stops the cries of “vote-splitting” often cast at non-establishment candidates under FPP. Progressive Hamilton mayoral candidate Louise Hutt says the city’s FPP system discourages campaigns like hers because they’re seen as taking votes away from other candidates. “I had one mayoral candidate, before I even announced I was running, come up to me at a public meeting and accuse me of intending on ‘stealing’ votes from them,” she says. “That competitive mindset is really prevalent in FPP elections.” Other people approached Hutt to say there were now three “good” female candidates for mayor, and her campaign would stop any of them being elected. “That’s how people feel in a first past the post system – competitive to the point where they actively discourage others to run. We should be stoked with more candidates because it should mean more options for voters, and especially ‘good’ candidates.”

There’s hope STV would encourage more insurgent campaigns like Hutt’s, or Chlöe Swarbrick’s run for the Auckland mayoralty in 2016. The current dominance of middle-aged Pākehā men in local politics is a kind of feedback loop, where the election of staid white candidates discourages young and diverse voters, which leads to the election of more staid candidates. Young and diverse candidates are more likely to get elected under STV, which could in turn encourage those demographics to vote.

Aaron Hawkins has seen that effect first-hand. He is in with a shot of becoming New Zealand’s first Green Party-affiliated mayor at this year’s Dunedin election, despite running in a large field of candidates, many of whom are from the left of the political spectrum. Without STV, splitting the vote is often a reason given for not challenging incumbent mayors and councillors, or the reason that incumbents are more comfortably returned, he says. “I think FPP is far better at entrenching the status quo, and that’s unhealthy for the democratic process,” he says.

But if none of that matters to you, there’s one other good reason to adopt STV for all local council elections nationwide: it’s just less confusing.

At the 2016 elections in the Tasman District, 1500 people spoiled their ballots, most of them by accident. The voters were confused. They’d gone through the first set of papers, ticking the box next to their preferred candidates, then flicked the page to their DHB election ballots and kept ticking. Unfortunately those DHB ballots were thrown out. Voters were meant to be ranking the candidates.

Like most others around the country, Tasman’s elections use two different voting systems – FPP for its council and legislativiely mandated STV for its District Health Board. That split has been shown to cause confusion. When Wellington transferred to a full STV system for all its elections, including regional council and Capital and Coast DHB, the number of informal – or spoiled – ballots reduced drastically.

For Tasman resident and former Golden Bay city councillor Liz Thomas, the answer was obvious: get rid of FPP. The Local Electoral Act gives councils the ability to decide to keep FPP voting every six years, and Tasman Council had unilaterally decided to keep the FPP/STV voting split without putting it to a referendum voters in 2017. But the act also allows citizens to force a referendum on the issue if they get the signatures of 5% of enrolled voters. Thomas organised a petition, rustling up a team of volunteers to canvas the disparate corners of her vast 9786km² electorate. They gained 2400 signatures – enough to put the referendum on the ballot at this year’s local election.

For Thomas, part of the motivation for the effort was a belief that voters should have their say on the system they use to elect their representatives. But it’s also about council looking like its community, she says. Tasman District Council is 80% male. It has no young people. That has the effect of suppressing votes, because when people don’t see others like themselves in government, they don’t engage with it, Thomas says. “Not just in Tasman District, but in other places, people say ‘what’s the point?’ and we don’t make an impression. But I kind of feel if we had more diverse councils that look like the communities they represent, people would get more interested again.”

As much as Thomas’ efforts are admirable, they’re also exhausting and time-intensive thing to expect of voters, particularly on a subject that doesn’t exact light people’s imaginations on fire. Hayward says it’s unreasonable to charge local democracies with painstakingly changing their voting systems one-by-one by way of referendums, especially when they’re faced with the threat that self-interested local councillors will just vote to change them back to FPP six years later. She sees government legislation to enforce STV across New Zealand as the only feasible solution.

“We know politicians are so self-interested in government – why on Earth would we ask them which electoral system is best? But for whatever reason central government decided this was a local issue and they ought to allow councils to decide. And so no surprise, councils being conservative, have been really reluctant to change. And it’s really hard for communities to get up the polls to change this. So it’s hopeless right? It’s not going to go anywhere. We really need the system changed in a mandatory fashion by central government,” she says.

Hutt echoes that call. Councillors will never willingly change the system that got them elected, she says. “It’s unfortunate that ego and complacency around the status quo are pervasive in our local body councils. We know STV is more representative. We know it’s a fairer system. And if councils aren’t prepared to provide that for their citizens, central government should step in and do the right thing.”

Government unilaterally deciding to simplify our local government voting systems could be controversial. Switching to mandatory STV may generate angry tweets from both David Seymour and David Seymour-adjacent people. But the price of staying the same is leaving local government as the fiefdom of a few hundred perennially elected old, white men. Change could cost a little bit of political inconvenience. Sticking with the status quo is costing us a functioning local democracy.

*Before Graeme Edgeler contacts me, I do know drawing a picture of a dog turd would technically be spoiling your ballot.