The World Health Organisation pulled its support for acupuncture in 2014. The Ministry of Health has found barely any evidence of its efficacy. So why is ACC still paying out millions for acupuncture treatment?

This investigation is made possible by Spinoff Members. To support independent, homegrown journalism, donate today.

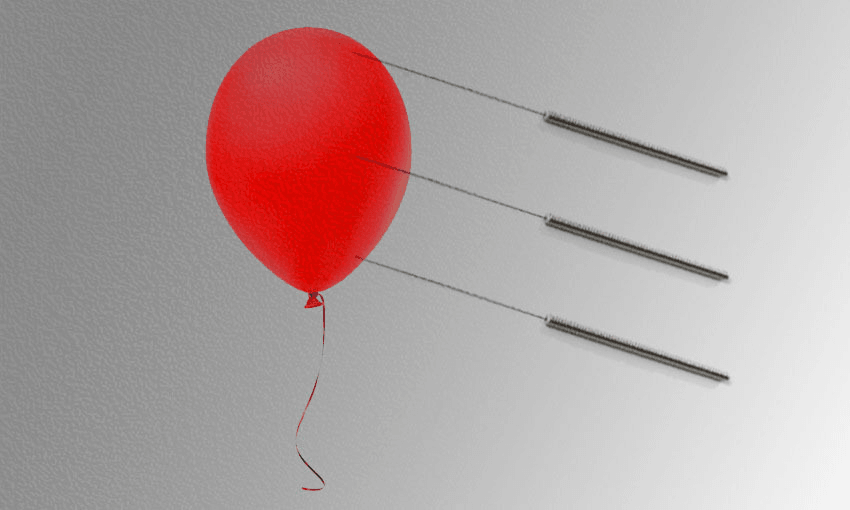

There are about 650 practitioners of acupuncture in Aotearoa and every one of them walks a tightrope. The task is to convince customers they’re selling something that works, while not tipping over into promising that it will. Prudent practitioners go softly-softly, with words like “stimulates” and “promotes”, which is about as surefooted as their claims can get.

Others go rogue. As New Zealand entered level four lockdown, with fear of Covid-19 at its peak, Integrative Acupuncture in Silverdale, Auckland, suggested in a blog about the coronavirus on its website that people should “Book your acupuncture treatments, see your chiropractor, …take your supplements. These practices are awesome ways to keep yourself healthy and to give your immune system a boost.”

As members of the Society for Science Based Healthcare, we believe that a strong basis in rigorous science is a necessary prerequisite for providing safe and effective healthcare. Our complaint to the Advertising Standards Authority saw Integrative Acupuncture scale down its claims, including that acupuncture treatments can give “your immune system a boost”.

Here’s the thing: you’re not allowed to claim that acupuncture cures or significantly improves medical illnesses and injuries, because there’s not nearly enough evidence to prove it does.

The pattern in the research has been obvious for many years: the better controlled the study, the less effective acupuncture is proven to be. The most rigorous studies show no clinical effect at all. A huge number of the studies on acupuncture (and there are some 30,000 on PubMed) are so badly flawed as to be meaningless.

Given all of that, it hardly seems something that public dollars should be poured into. And yet ACC is doing exactly that. It is directing millions into acupuncture treatments every year, with no endorsement needed from mainstream doctors, and surprisingly little oversight of exactly how its huge spend is helping clients.

According to acupuncture theory, inserting needles – or performing related procedures including gua sha (skin scraping), auricular (ear) acupuncture, moxibustion (burning of dried mugwort near the skin), electro-acupuncture, tui na (massage) and cupping – rebalances the flow of a mysterious energy called Qi within the body. We have been unable to find reliable evidence proving the existence of Qi, or the meridian points it is supposed to flow between.

Experts from Yale and University College London put it bluntly in 2013, heading an Anesthesia & Analgesia paper “Acupuncture is Theatrical Placebo”.

While some medical organisations continue to recommend acupuncture in a limited setting, significantly, the World Health Organisation has withdrawn its support. In 2002 it published an influential report listing 90 conditions for which acupuncture may be indicated, but pulled that report in 2014 “in response to substantial evidence contradicting the WHO’s advice”.

Trawl through the Ministry of Health’s website and you’ll find very little support for acupuncture’s use as a treatment. The ministry advises against acupuncture’s use for stroke management, thrombocytopenia, bleeding disorders or aplasia. It says there is insufficient evidence in the case of depression, melanoma management, kidney disease or cardiovascular disease. For smoking cessation, it says the data shows that acupuncture is ineffective. The only exception we found is a document about cancer support and rehabilitation, which notes acupuncture has “a therapeutic role” in cancer fatigue, and may reduce chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

In response to questions, the ministry provided The Spinoff with the following statement: “The Ministry of Health does not currently have a position on the effectiveness of acupuncture as a treatment modality. We are aware that ACC has completed a review of the acupuncture literature. A Ministry of Health representative is part of the ACC Acupuncture Purchasing Advisory Group and we are working to understand what it means for the purchasing of acupuncture services.”

Others have been examining the evidence, too, of course. For example, in 2019 the journal Medicina published a paper synthesising 177 reviews of acupuncture across 30 years. Conclusion? “The large quantity of [randomised controlled trials] on acupuncture for chronic pain contained within systematic reviews provide evidence that is conflicting and inconclusive, due in part to recurring methodological shortcomings … It is essential that the quality of evidence is improved.”

But arguably the most damning evidence are the Cochrane reviews. These high-quality, independent studies are widely considered the gold standard in global health science. By 2014, notes one Australian paper, “over 60 Cochrane reviews failed to support the majority of claims of effectiveness”. Recently Dr Edzard Ernst, former professor of complementary medicine and the co-author of the book Trick or Treat: Alternative Medicine on Trial, completed his own review of all 64 Cochrane reviews on acupuncture and found “there is hardly a single condition for which acupuncture is clearly, convincingly and indisputably effective”.

So what is ACC thinking? Chief clinical officer, Dr John Robson told The Spinoff: “We make funding decisions based on the legislative framework, best available published evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values.”

You might expect “best available published evidence” to decisively strike out acupuncture as a candidate for funding. Especially as ACC’s own documents show it’s well aware of the state of the science. In 2014 it reported on the effect of acupuncture on various mental health conditions, for example, and in 2018 it reported regarding musculoskeletal conditions like neck pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, fractures and osteoarthritis. In both cases it concluded there was insufficient evidence of efficacy.

That did not stop ACC funding acupuncture treatment – and Robson says 94% of its spend goes on musculoskeletal conditions.

According to Robson, the 2018 report “showed there is some evidence that acupuncture is an effective treatment option for short-term pain relief associated with musculoskeletal condition, but there is little evidence of medium (6-12 weeks from start of treatment) or long-term relief of pain”.

In scientific literature, the term “some evidence” in a conclusion is in our experience usually followed by a recommendation that further research is required before a therapy is used as a treatment. In this case, though, ACC appears to have accepted “some evidence” as a sufficient threshold to fund a therapy.

Its acupuncture spend has been trending up: $33 million in 2016/17; $44.3 million in 2018/19. The bill for 2019/20 is predicted to hit $49.2 million; latest figures, collected after lockdown, shows that spending on acupuncture was $37.2 million for the period July 1 2019 to May 10 2020.

What’s the harm? Well, that’s a lot of taxpayer money, for a start, especially given the exceptionally bleak economic outlook. But also: to fund a therapy is to endorse it.

A real danger is that some will choose acupuncture over treatments that are proven and effective – and that they desperately need.

Further, some might be injured by the acupuncture itself.

It’s very difficult to pin down how common this is. We have been unable to find official data on adverse events linked to acupuncture in New Zealand, and while Acupuncture NZ does collect reports of more serious adverse events, it has so far declined to share those with us.

The Spinoff approached regulatory bodies Acupuncture NZ and the New Zealand Acupuncture Standards Authority for comment on the issues raised by this story. Despite multiple approaches, neither regulatory body had responded at the time of publication.

Some of the most serious cases come to light after investigations (triggered by complaints) by the NZ Health and Disability Commissioner. In four cases we found, an acupuncturist’s needle punctured and collapsed a person’s lungs. The most recent was in 2018. A woman went to an acupuncturist seeking treatment for an injury to her arm and wrist. The acupuncturist inserted long needles at the “Jian Jing” points on her shoulders. As the needles were inserted, she felt pain and discomfort. Despite this pain, the needles were left in for 30 minutes and rotated. When the acupuncturist finally removed the needles, the woman felt a sharp pain and experienced shortness of breath. That evening, her husband took her to a medical centre, and then to the hospital, where it was discovered both lungs were punctured.

Health and Disability Commissioner Anthony Hill found the acupuncturist had caused the lung damage. He also found that the woman had not given informed consent, as there was no written record she had been told of the risks involved.

The clinic was told to make sure other customers had received information brochures and provided written consent for procedures; that it must develop formal policies and procedures on informed consent; and that the acupuncturist receive further training. The acupuncturist was not named, despite the serious harm done.

This is not a one-off. In 2017, writing about a 27-year-old man left with a punctured lung, Wellington Hospital doctors warned such cases are likely to be under-reported. They wanted to raise awareness of this rare but potentially life-threatening complication of acupuncture:

“As of July 2016, the website of Acupuncture NZ only describes minor bruising as a complication. A 30-year Chinese review of 115 published articles described a number of serious complications, including 201 cases of pneumothorax [punctured lung]. Two prior cases of pneumothorax following acupuncture have been reported in New Zealand, though the true incidence is likely to be under reported.”

Others have raised flags: in 2012, the UK’s National Health Service, which funds some acupuncture while acknowledging there is “not strong evidence” for its use, revealed that a search of records spanning three years found 325 acupuncture-related “patient safety incidents”. While a handful were extremely serious, most were classed as minor, such as dizziness, fainting or needles being left in too long. (Sometimes much too long: “In 59 incidents, the needles were found by patients either on their way home or at home.”)

The NHS noted: “Frustratingly, since there is no information on how many acupuncture treatments were given within the NHS during the same period, we do not know how common such harms are.”

In 2017, the gold-standard science journal Nature published an overview of systematic reviews on the safety of acupuncture, noting underreporting of adverse events, and “mediocre” data quality. Serious complications were rare, “but need significant attention as mortality can be associated with them”. Some acupuncturists had never reported an adverse event, “raising the question of whether some practitioners are even aware of complications in their patients”.

Meanwhile, a systematic review published last year in the peer-reviewed Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies found that even trained and qualified acupuncturists disagreed over a basic tenet: where exactly to stick the needles.

“The degree of variance in point localisation among practitioners is sufficient to raise concerns regarding safety and efficacy of treatment,” researchers warned. “A number of acupuncture points lie in close proximity to arteries and other structures prone to damage by needling… Serious adverse events associated with acupuncture treatment are rare; however, local trauma, neural injuries, aneurysms, injuries to the eyes, and broken needles are all potential adverse outcomes that have been reported due to the incorrect site being needled.”

Not all acupuncturists are prudent in their promises. Remember the tightrope?

In 2017 the New Zealand Medical Journal published a paper by Daniel Ryan (one of the authors of this article) detailing more than 100 acupuncture websites in New Zealand that were potentially breaching Section 58 of the Medicines Act. This prohibits the publication of advertisements claiming the ability to prevent, mitigate or cure a range of serious diseases. Many of the sites Ryan found claimed acupuncture was able to treat conditions such as mental disorders, infertility, arthritis, blood pressure problems, sexual impotence and diabetes.

There is little sign of officials doing much to curb such oversteps. As of today, the website of regulatory body Acupuncture New Zealand features a page headed “What Conditions Can Be Treated With Acupuncture?” An extensive list follows, ranging from relatively minor conditions such as constipation and insomnia through to those that could be fatal if not promptly treated by a medical professional, such as kidney disease, influenza and chronic pulmonary disease. It even claims that acupuncture can treat Alzheimer’s.

“Those conditions in bold italics have been found to have moderate and/or strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of acupuncture,” Acupuncture NZ states, linking to a “comparative literature review” which was financed by the Australian Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine Association and does not appear to have been peer-reviewed or published in a medical journal. Many of Acupuncture NZ’s members, who are ACC treatment providers, have copied this list to their own websites.

Follow the link to the review itself and you’re met with a page of warnings about misleading advertising, including: “While the findings of this project might be used to inform clinical decision-making, it should not be relied upon to make claims in advertising.”

Often, says ACC’s John Robson, doctors will refer patients for acupuncture “if they believe it is an appropriate and necessary treatment option”.

But in other cases, the doctor simply lodges the ACC claim and decisions about treatment are left with the patient – and the acupuncturist.

Say you hurt your shoulder at the gym. You visit your GP and they lodge an ACC claim (alternatively, a physiotherapist or osteopath can do this for you). It’s accepted. You can then visit an acupuncturist and receive treatment for that injury, and your acupuncturist will be paid by ACC.

Crucially, acupuncturists get to decide which ACC-covered injuries they can treat. And it’s hard to imagine that they’re turning many clients away: according to Acupuncture NZ, “because Acupuncture and Chinese Medicine is a complete health care system, there is very little that does not benefit from a course of acupuncture, herbal medicine or a combination of both.”

Information provided to us under the Official Information Act shows ACC has paid acupuncturists to treat a wide variety of conditions such as burns, soft tissue injuries, sprains, fractures, punctures, stings, foreign bodies in tissue, dental injuries, hernias, and even mental health issues and amputations. All of which will cost the taxpayer an estimated $49.2 million for the year ending June 30.

But properly parsing the millions being poured into acupuncture is impossible because ACC takes a broad-brush approach to data collection. It does not record which aspect of the injury is being treated (for example, whether it’s short or longer-term pain, or muscle or tissue damage) or which particular treatment is being used. It could be classic acupuncture using needles, or it could instead be cupping, lasers, skin rubbing, massage or the burning of herbs.

The Covid-19 pandemic underscored the broad public appreciation for a consensus of evidence-based, expert scientific opinion.

“We’ll always base all our decisions on evidence,” Jacinda Ardern promised in a recent Covid-19 press conference.

This is a laudable position to take, but it doesn’t go far enough. The government must now extend this manifesto to existing government policies – and limit ACC funding to those therapies that have solid ground to stand on.

Daniel Ryan is a committee member of the Society for Science Based Healthcare (SBH) and author of “Acupuncture, ACC and the Medicines Act”, a review of therapeutic claims offered by acupuncturists, published in the New Zealand Medical Journal.

Jonathon Harper is a fellow member of SBH whose investigation into public funding of homeopathy courses was published in the January issue of North and South. The Society receives no funding and is run by volunteers.