From Lorde’s whisper-pop to Jack Antonoff’s anti-irony, Elle Hunt dissects how pop music is changing now, after nearly 20 years in a Max Martin sugar rush.

Melodrama didn’t win album of the year at the Grammys last month. But it had always been a long shot.

The Grammys tend to recognise legacy or commercial success, and though it had been well received by critics, and appeared at the top of the Billboard album charts in its first week, Lorde’s sophomore album had not exactly set the charts on fire (it came in at 114 on Billboard‘s year-end chart). ‘Green Light’ was the best-performing of its three singles, peaking at 19 on the Billboard Hot 100. By comparison, among the five singles of Bruno Mars’ winning 24K Magic was his seventh number one.

Ella Yelich-O’Connor, already a two-time Grammy winner at 21 years old, seemed magnanimous in defeat, conspicuously swigging from a hip flask and tweeting about meeting Cardi B and “Prez” Jay-Z. She didn’t win another Grammy, but she hadn’t needed to. She’d already won pop music.

The sound that Lorde had ushered in nearly five years ago with ‘Royals’ and Pure Heroine seemed to peak in 2017. She may not have dominated the charts herself, but her influence could be heard up and down them, even as Melodrama indicated she was moving in a new direction.

When Pure Heroine was released in 2013, Macklemore’s ‘Thrift Shop’ was the year’s best-selling single, topping the Hot 100 for four weeks before succumbing to the hypnotic assault of Baauer’s ‘Harlem Shake’. (It later returned for a two-week victory lap.) ‘Can’t Hold Us’, also by Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, was another defining song of the year, along with ‘Blurred Lines’, Katy Perry’s ‘Roar’, and ‘Wrecking Ball’ by Miley Cyrus.

When ‘Royals’ began its nine-week rule of the Hot 100, it sounded like nothing else on the charts. By pop standards, ‘Thrift Shop’ (95 bpm) and ‘Roar’ (90 bpm) weren’t fast by any means, but at 85 bpm, ‘Royals’ was slower. ‘Blurred Lines’, the inescapable song of the North American summer after 12 weeks at number one, was pacy and fleshed out, with a jaunty cowbell and a message that didn’t stand up to scrutiny. ‘Royals’ was stark and spacious, attempting not only a new sound but a social critique, and the album was similar.

‘Loads of girls who were like Lorde’, and the rise of whisperpop

Listening to Pure Heroine today, the only clue that it’s nearly five years old are the crisp and mechanical drums – nothing like the anthemic ‘80s style currently enjoying a comeback. Apply that gated reverb to ‘Team’ or ‘Tennis Court’, make them minor key, and you’ve got a 2017 hit: 100 or fewer beats per minute, processed voice serving as an instrumental hook (“Yeah”), layers of synth and cavernous reverb, a melodic range of only a handful of notes per chorus, and intimate vocals.

That almost conversational style of singing is now so ubiquitous, it’s easy to forget it would not have been associated with pop ten years ago or fewer. Compare Lorde’s melodic approach to that of Mariah Carey, Kelly Clarkson, Alicia Keys, Pink, Lady Gaga, Kesha, Ariana Grande, Katy Perry or Taylor Swift. They project their voices and aim for a full-bodied sound and fluidity, sometimes audibly straining to achieve it (Swift is out of her comfort zone at many points on Red). ‘Royals’ is perhaps the most concerted display of vocal mastery on Pure Heroine, and it’s hardly giving Adele a run for her money.

That’s not to say Lorde can’t sing – obviously, she can. But five years ago her hushed intensity was a new proposition for pop music, and one the industry has gone onto embrace wholeheartedly. Popjustice’s Peter Robinson called it “whisperpop” and, in a recent feature, credited Lorde (and Lana Del Rey) with its popularity. An anonymous artist he quoted linked her own signing to Lorde’s success: “labels were wanking over trying to get loads of girls who were like her”.

The effect of this became clear last year, when slow and sad-sounding songs were the norm for the first time in decades. Analysis by the gossip site Popbitch found that a remarkable 87% of 2017’s number-one songs were in a minor key, up from 62% in 2016 and just 29% in 2015.

Popbitch blamed global instability: “Things have been getting steadily more bleak in the world at large, and in pop charts, too”. Slower, longer songs also reflect the fact that streaming means they no longer have to be kept to three minutes’ duration (though, for the record, they should be). But the overarching trend towards a bluer mood can also be linked to Lorde.

You can hear elements of post-‘Royals’ pop in ‘Hands to Myself’ and ‘Bad Liar’ by Selena Gomez, ‘New Americana’ and ‘Now or Never’ by Halsey, ‘Gold’ by Kiiara, ‘Here’ by Alessia Cara (the Grammy’s Best New Artist), Troye Sivan, Banks – even ‘Blank Space’ and ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ by Taylor Swift. But there is another reason for that beyond changing times. Its name is Jack Antonoff.

‘Irony is emotional death’: The ‘Antonoff-isation’ of pop music

In 2013 Antonoff was perhaps best known as Lena Dunham’s boyfriend (they confirmed their breakup earlier this month) and for ‘We Are Young’, his band fun.’s first number one. Today he is the producer of the moment, having worked on Taylor Swift’s Reputation, the best-selling album of 2017 (though excluded from the Billboard chart mentioned above due to its release date), and St Vincent’s Masseduction, one of the best albums of 2017.

If a hit song today is not produced by Antonoff, it’s apeing his sound (unless it’s trop house, which, please, enough already): the rumbling tectonic synths, louder-than-life drums, syncopated rhythms and looping electronic circuits. Think ‘Out of the Wood’s, one of his three songs on Swift’s 1989 – Antonoff has made his name crafting ‘80s throwbacks for the generation that came after it (he himself was born in 1984).

Antonoff is set to usurp super-producer Max Martin as the person you call for a surefire hit, and the moment is ripe for him to take over. Martin – whose name, it is barely an exaggeration to say, is in the liner notes for every number-one since ‘Quit Playing Games With My Heart’ – specialises in sugar-rush pop, the songs of the summer that make you feel on top of the world, even if the lyrics don’t always make sense.

Martin’s “melodic math”, where words’ meanings matter less than their number of syllables, contrasts with Antonoff’s stated approach of rooting out “the saddest, most upsetting, most real things someone might go through, and then finding a way to sew those into pop songs”. It seems telling that the pair of them roughly split the production of Reputation, one of last year’s most highly-anticipated albums. In a world tending towards slower, sadder pop songs, Martin’s winning formula may not add up the way it once did.

Plus Martin’s name is inextricably linked to Lukasz “Dr Luke” Gottwald’s, his protege and collaborator, whose production discography has been eclipsed by his court battle with Kesha, and her accusations of sexual assault and harassment. After a judge denied Kesha an injunction in 2016, Antonoff publicly tweeted at her to suggest they collaborate, calling Dr Luke “that creep”. Lindsay Zoladz pointed to this exchange in The Ringer in November to pose the question: was Antonoff “the cure for Dr Luke?”

Certainly his approach couldn’t be more different to that of the notoriously prescriptive Gottwald. Antonoff has often (too often, arguably) spoken in interviews about his preference to work with women who are “brutally honest” about their feelings, instead of men who “hide and mask emotions”. St Vincent’s Annie Clark described her time working with him as though it were therapy (“he changed my outlook on life”). His ethos, she said, was to “go for the jugular – irony is emotional death”.

It makes sense that Antonoff chooses to work with artists who wear their hearts on their sleeves, where he can get at them. Skip through Popjustice’s Antonoff: More On Than Off playlist on Spotify, and the common thread soon becomes obvious: his songs are wistful, earnest, romantic, anthemic. This inclination to bring a bit of Springsteen’s Born to Run to every table is most obvious in his own musical projects, fun. (“What do I stand for? Most nights, I don’t know anymore/This is it, boys, this is war”) and Bleachers (see the emailed preamble for ‘Don’t Take The Money’, co-written with Lorde).

In Antonoff’s world, life and love is high drama and fundamentally cinematic in scope. The single most telling fact about him is that he immortalised his high school bedroom in a trailer so that he could take it with him on tour. On this nostalgia for the teenage experience, and the artistic pursuit of emotional honesty, he and Lorde are aligned, describing her on a red carpet as “very relentless to get things right, and as close to the heart as possible”. Pure Heroine, you get the sense, set the scene for a sea change in pop music that Antonoff is now in the business of cementing.

Kindred spirits

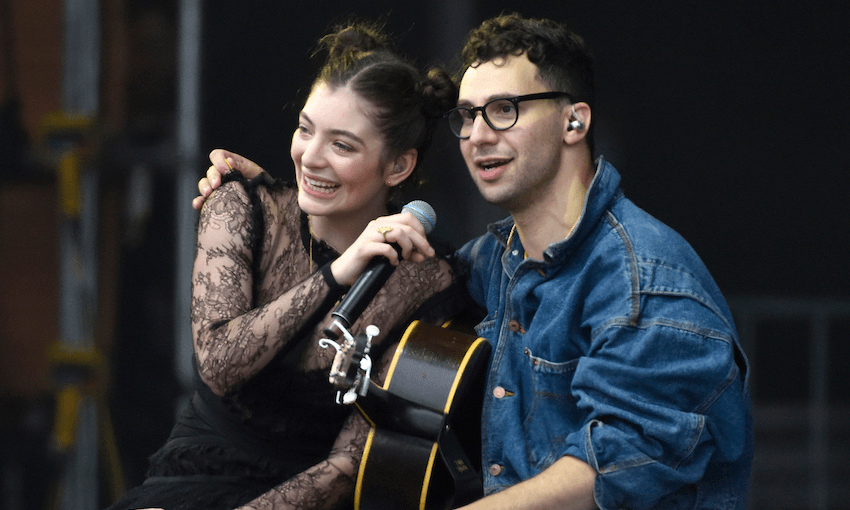

With Antonoff credited on all but one song on Melodrama, and its sole other listed executive producer alongside Lorde, the album bears his fingerprints more obviously than Masseduction, and certainly Reputation – perhaps reflecting the intense bond of which it was born. They spent months working on Melodrama together, mostly in Antonoff’s home studio in Brooklyn. “I miss going literally everywhere with this bud,” Lorde captioned a paparazzi photograph of the two of them on Instagram.

Their relationship was so publicly fond that in the wake of his breakup, Antonoff felt moved to reject speculation about it on Twitter, grouping it among “the most important friendships and working relationships in my life”. Lorde favourited and retweeted it.

Melodrama, the product of that “deeply important and sacred” bond, was praised for its emotional honesty and the powerful picture it painted of finding oneself again after a breakup. Its ambition – and even its lack of chart-friendly singles – reinforced Lorde’s reputation as an open book and an outsider within the industry, and also invited contrasts with Reputation, Swift’s least “authentic” album yet.

The Cut’s Ask Polly advice columnist Heather Havrilesky made comparisons between the two explicit in advising an aspiring writer on how to find their voice, praising Lorde as “an artist who is completely upfront and frank about her conflicted state”. Reputation, meanwhile, “is all about reacting to what other people think of [Swift], and then trying hard to make that reaction sound triumphant and powerful”.

Regardless of what exactly it had revealed, the Kim Kardashian-Snapchats-receipts saga exposed calculations and contrivances bubbling behind the scenes of pop music, and Reputation set them to music. Its rap-adjacent posturing, its big-name feature spots, and its amalgamation of every contemporary musical trend smacked of cynicism and commercial imperatives. (To be clear, I like much of Reputation.)

“The knock against Taylor Swift records is that they neatly summarise pertinent developments in the music of the present when they could be using their power to point the way to the future,” wrote Craig Jenkins in his insightful assessment of pop in the 2010s. “Like everyone else, [with Reputation] she’s trying to match what’s on the market rather than distinguishing herself from it.”

With Reputation, then, Swift was attempting to dominate the sound that Lorde had played a part in pioneering, at the same time as Lorde herself took steps to move away from it. Melodrama in many ways bucked the trends that she had popularised. ‘Writer in the Dark’ was a blow to whisperpop, suggesting a return to capital-S singing. ‘Homemade Dynamite’ was up-tempo at 107 bpm. ‘Green Light’ starts off in a minor key then shifts to major, unexpectedly and “like a small sun rising”, to quote the New York Times Magazine.

No wonder Melodrama didn’t win Album of the Year. Lorde has always been ahead of her time.

Jack Antonoff (as Bleachers) plays Spark Arena on Tuesday 13 February, supporting Paramore.

The Spinoff’s music content is brought to you by our friends at Spark. Listen to all the music you love on Spotify Premium, it’s free on all Spark’s Pay Monthly Mobile plans. Sign up and start listening today.