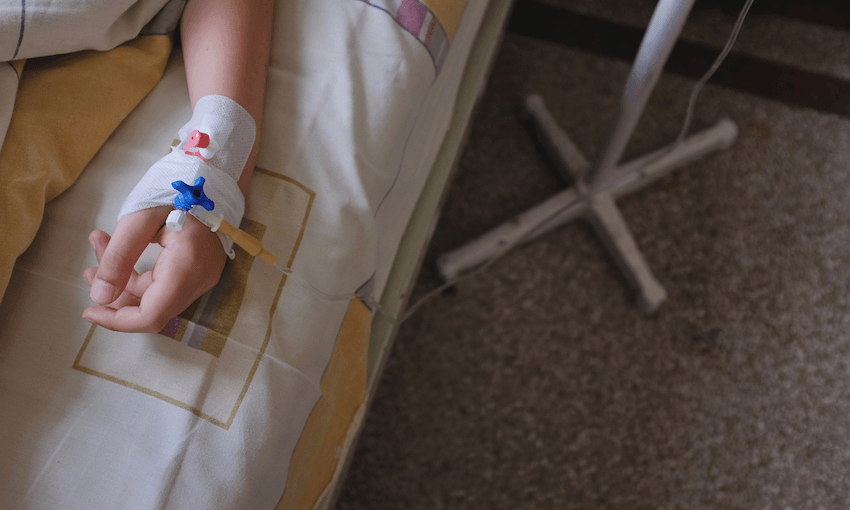

Emily Writes on love and fear and hope at her son’s hospital bed.

I hate horror films with monsters in them.

I am skilled at fearing almost everything in my day-to-day life so I find little joy in being professionally scared in a cinema. I fear almost everything from bee stings (I’ve never been stung so how do I know I’m not allergic) to The Dark (anything could be out there). My husband is awed by my ability to be afraid of mundane things.

I am exactly the wrong person to parent a child with a serious chronic illness.

And yet here I am, on ward one again.

There were times when my son was a baby when I thought the beeping here might actually cause me to completely lose my grip on reality. The symphony of a hospital ward is frightening. It has no rhythm and it changes too quickly to get a handle on it. You can’t pull the notes from the heavy air to order them. Whenever I read about big budget horror films with soundtracks designed to make you nauseous I just think it’s all very unoriginal. I could make you one.

Beep. There goes your life as you knew it.

Beep. Who knows what day it is.

Beep. Nothing will ever be the same again.

It’s all mundane thrillers in suburban brick hospitals. It won’t sell any tickets. But somehow I’m back in this same low-budget horror.

When he got better after three years I found that I still couldn’t breathe quite right. I always felt like the moment when the monster appears behind the girl who is staring in the mirror.

Every day was like that for at least a year. Then I realised that my fear was getting in the way of everything. He was better – so I needed to be better. I thought talking about it would help, so I did. And it did. I slowly got better too. No more frights.

And then last week was a normal week. There was a new bug – same old, same old. Except suddenly out of nowhere it all went dark.

There was a new monster to fight. And it came as such an awful shock that I thought – I should have known, and I should have been ready for this.

But I don’t know that you can live your life holding the phone to your ear, knife in your hand the call is coming from inside the house. You can’t hold your breath for that long. You have to be able to release your shoulders.

And I did.

And now the ache is back. The barely able to breathe through it all – it’s back.

The other night I lay with him and I whispered “I’m so sorry”.

I thought he was sleeping.

I said “It’s not fair”.

And he whispered into the dark “What’s fair?”

What can you say?

This whole ward is full of not fair and it doesn’t make any difference.

He fell back into sleep. And I stood up. Took a deep breath. I began to read the booklet about his new diagnosis. My husband had highlighted parts. I googled the words I didn’t know. Watched the Youtube clips on the diagnosis website. Practised pulling exactly 6ml into the syringe over and over. Facetimed my husband as he explained the counting.

Across the world in every ward there are parents. And they didn’t think this would be it. This is not the monster they thought they would face.

But the monster is here. And the mother who has just found out her daughter has Coeliac disease colour codes her Tupperware so that her child’s damaged bowel isn’t further at risk. In the dark while everyone sleeps she reads recipes. And the father who just heard his child has kidney failure googles kidney transplants and reads about what he needs to do to give of himself. The aunty who loves the child like her own books a ticket across the world to be there when her niece wakes from the removal of her tumour. The grandmother marks every chemo date on the calendar. The mother who never knew there were two types of diabetes learns how to keep blood coming long enough from a tiny finger to measure ketones. The father writes a long email to the child’s kindergarten about training for EpiPen use. The mother can tell her daughter is seizing from the other side of the room even as she makes toast for her eldest child and stacks the dishwasher.

There’s something that happens when the monster comes. It’s a terrible kind of magic. It’s parenting in its truest form. The “drop everything and do everything” part of parenting. It feels like torture having your heart as an open wound but your heart is all you have.

And you’ll do anything.

Anything.

And in comes the doctor and for a second you see them in their early 20s. An image of study, deep in thought. What made them want to do this difficult but important work? They worked so hard to be here and now they’re here and by cosmic force they can help.

And the nurses know exactly what the chart says and everything is accurate and measured correctly and they work so gracefully that sometimes you’re a little spellbound. They have an ability to smile at you in such a way that the air momentarily clears.

And the room is cleaned somehow in the time you were stroking your child’s forehead lost in the freckles on their nose. And a pack has been left – shampoo, toothbrush, toothpaste, comb. Lovingly put together for you and everyone like you by someone else who might have walked these floors before.

The fight isn’t alone. The risotto in the fridge is made with extra veges to keep you strong. There is love written on the lid. The neighbour walks your dog, brings you treats. The children write in cards in lettering that spills down the page “We love you get well soon”. The fudge and the coffee vouchers, the koha for the bills and the bills and the bills.

If there was a soundtrack to this it’d be a wedding march.

All the love and expectation, the hope and the commitment to something greater than this.

A community rallying, a standing ovation for all of the little children. A cry of encouragement for the parents who will somehow rise up to the challenge. Because they just do. This isn’t a horror, this isn’t tragedy. It’s a love story.

Look at this team. Protect the heart. Protect the child.

The monsters don’t stand a chance.