Maternity care is meant to be free in Aotearoa, yet some expectant parents are paying hundreds of dollars for obstetric scans. For IRL, Madeleine Holden digs into what’s gone wrong.

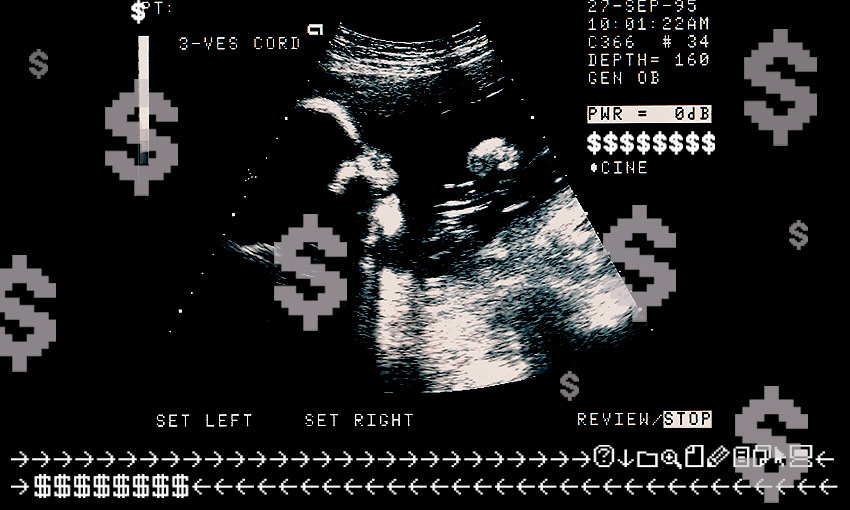

There are few social media posts quite as precious (and like-worthy) as a pregnancy announcement, and the perfect vehicle for this news – especially if your baby bump is still forthcoming – is the image from an ultrasound scan. Celebrities like soccer player Cristiano Ronaldo, socialite Kylie Jenner and Bachelor NZ participants Art and Matilda Green have all shared those heartwarming black-and-white pictures with their hordes of followers, and ordinary New Zealanders also use these images to surprise loved ones with their good news, whether in person or online.

For the famous and non-famous alike, ultrasound scans are often exciting events in the course of a pregnancy: expectant parents can see their baby for the first time, find out whether they’re having multiples, and receive updates on the baby’s growth and development; many report the 20-week scan, when the sex can be determined and the baby is looking most baby-like, as a particular highlight. Tears are often shed; print-outs are regularly framed or used as props for gushing Instagram posts.

But there’s an unspoken downside to this medical procedure, and the cherished images it produces: in this country, it can come at a significant – and often unexpected – cost.

Rebecca, a 31-year-old Auckland resident who is currently 25 weeks pregnant, was told by her GP at the six week mark that she wouldn’t have to pay for maternity care during her pregnancy. “It was a relief, and it made me feel quite proud of the social safety net we have in this country,” she says. She was caught off guard, then, when she was charged $30 for a dating scan, $50 for an additional scan to monitor a complication, then $150 for her 12-week scan; costs she says she got “no heads up” about, from her midwife or anyone else.

The element of surprise had worn off by the time Rebecca was charged another $100 for her 20-week anatomy scan (she went to three different providers in the Auckland region), but by that point – with her pocket already $330 lighter, halfway through a singleton pregnancy – she felt “a bit less impressed by our healthcare system”.

Charlotte, an Auckland-based mother of a toddler and 10-month-old, also found herself “very surprised” to be charged for scanning during her second pregnancy. “I had my daughter in London in 2017, and maternity costs were covered there, including scans, because they are an integral part of monitoring your baby’s health and growth,” she says. Because her first child had a low birthweight, her midwife said she would need regular growth scans during her second pregnancy in Aotearoa and recommended she purchase a scanning package at Ascot Radiology for $475.

“I didn’t understand why scans were considered private,” she continues. “I was surprised it was a cost you had to pay because of my UK experience and considering everything else in maternal care was free [here].”

Like Rebecca and Charlotte, many women find themselves unprepared for the high cost of obstetric scanning they encounter during pregnancy, because they assumed, quite reasonably, that it wouldn’t cost them anything. “In New Zealand, most maternity care is free unless a pregnant woman/person chooses to arrange the care privately from a specialist doctor (obstetrician),” says Clare Perry, deputy director general of health system improvement and innovation at the Ministry of Health.

But the fine print can be found online: the Ministry of Health website clarifies that there “may be charges … for ultrasound scans.” It’s easy and common to miss this memo, though: if no one warns you about the cost and you don’t happen to be scouring government websites for exceptions to the rule, it can be surprising and frustrating to be charged hundreds of dollars after attending the scans your midwife recommends. For many women, it’s also hard to understand why this particular aspect of maternity care isn’t covered by public funding.

“It’s a joke that [scanning costs] aren’t covered,” Charlotte concludes bitterly.

According to Perry at the Ministry of Health, two scans are routinely offered during pregnancy: a first trimester screening at around 12 weeks gestation, and a foetal anatomy scan at around 20 weeks. However, many pregnant women are referred for a third “dating” ultrasound in early pregnancy to help determine how far along the pregnancy they are; other women, like Rebecca and Charlotte, will need extra scans if they have complications. “The average person is now having four to five scans in pregnancy,” says Dr Jay Marlow, Wellington hospital’s clinical leader of maternal and foetal medicine and women’s ultrasound.

Aside from the surprise of being charged at all, a further source of confusion for expectant parents is that there’s little consistency in cost across the various ultrasound providers, or across regions. By way of example, a single obstetric scan at Pacific Radiology’s Waikato clinic costs $45; the same service at Ascot Radiology in Auckland will set you back $150 for a singleton pregnancy or $290 if you’re having twins.

There can also be confusing inconsistencies even at the same provider. Jay, a 37-year-old mother to a 10-week-old newborn in Wellington, says she wasn’t charged for her dating scan and 12-week scan at Wellington Ultrasound, and was therefore surprised to receive a $60 bill for her 20-week anatomy scan and another $60 bill for a growth scan her midwife recommended in late pregnancy; costs she was only told about once she was already at the clinic. “No one ever told us which we’d have to pay for or why,” she tells me. “We’re lucky in that we could pay without a second thought, but it’s a bit like, ‘Why were the others free, and this one isn’t?’”

So why are pregnancy scans sometimes very expensive, and why does the cost vary so much?

Perry says that, in addition to the ultrasound services available in hospitals, the ministry provides funding at a national level to enable private community radiology practices to deliver this service, “thereby reducing pressure on hospitals”.

But the core problem, according to Dr David Rogers, head radiologist at Ascot Radiology in Auckland, is that this public funding for pregnancy scans has scarcely increased in 30 years. “In 1990, maternity benefits paid $79.60 per scan. Today they pay $92,” he says, citing GST-inclusive amounts. “Housing prices have gone up 10 times. The cost of petrol has gone up four times. The maternity benefit has gone up 15% in that whole time, and that is the crux of the matter.”

Marlow, who also serves as the medical director of Wellington Ultrasound, concurs. “We claim $80 plus GST per primary care maternity scan, no matter how difficult it is,” she says, explaining that this limited amount of public funding barely touches the sides. “Sonographers, their hourly rate will be somewhere between $50 and $70 an hour,” she continues. “Scanning machines are between $150,000 to $200,000. Then you’ve got rent and the receptionist and all those other overheads. You get charged for storing images, all that sort of infrastructure.”

To recover these costs, providers have three main options, short of operating at a loss. The first is to increase the volume of work they perform per hour, which runs the risk of reduced scan quality. “If you’re doing a patient every 10 minutes, then naturally you can charge three times less than if you spend 30 minutes doing it,” Rogers says. “We don’t believe we can do our job properly in less than 30 minutes, and we believe that people are cutting corners to do it in less than that.”

The second is to limit the amount of obstetric scans they perform compared to other more lucrative scans. Marlow points out that a carotid scan is $350 for half an hour, and an abdominal scan is $270. “We took the position that we didn’t think that was providing a community service,” Rogers continues. “We have an open appointment book and we don’t restrict obstetric scans, whereas most other practices in this town do.”

The third is to require a co-payment from patients, and for Marlow and Rogers, this is the least bad option. Providers set their own pricing, hence the inconsistency from place to place: Wellington Ultrasound charges different co-payments for different obstetric scans, depending on their complexity – that’s why frustrated Wellington mother Jay received different bills – whereas other providers charge a flat rate regardless of the type of scan.

Providers certainly aren’t profiteering from co-payments, Marlow says. “There’s not very much of a margin,” she tells me. “We don’t make too much of a profit, but we’re not in it for that. We’re in it to have good imaging and make sure people get good care.” Without the co-payment, she says Wellington Ultrasound “wouldn’t make ends meet”.

“We’re not making super profits here,” Rogers agrees. “We’re only paying our way.”

Why this reliance on private providers, though? Can’t public hospitals just provide scanning services directly, free of charge? In some circumstances, they do, but Rogers says the amount of obstetric scanning the public system provides is “woefully, woefully, short of supply”. “There’s not really much of an option for people to get their scan from within the hospital system,” he says. “Some do, but it’s quite hard work – it’s usually if they’re under the specific control of somebody in the hospital. So if they’re a hospital patient with a problem, then they get their scan done at the hospital. But that’s about it. There’s not a lot of community ultrasound done in the DHBs.”

The reason, according to Rogers, is there’s “no capacity for it” in the public system. “They basically don’t pay their sonographers enough, so they don’t stay in the public system and that’s why they’re short,” he continues. “They also don’t buy enough machines and fund them adequately. There’s a major gap between what is required from the DHBs and what they actually provide. So the load comes onto private practices.”

By way of response to Rogers’ comments, Perry says that “DHBs are responsible for providing or funding health services in their district that best meets the needs of their local populations,” although she notes that the upcoming transition to Health NZ will centralise and standardise the current devolved system. In allocating scanning services, Perry says DHBs factor in the urgency of the indication for the scan and the availability of appropriately-trained staff. She notes there is a shortage of sonographers in New Zealand and that DHBs make decisions about equipment purchase by “balancing a range of priorities”.

“Where there are issues of capacity, some DHBs may choose to outsource to a private provider,” she adds. “The Ministry acknowledges that the availability of maternity ultrasound scan appointments within DHB radiology departments is limited.”

Notwithstanding these limits, in some parts of the country, DHBs are opting to alleviate the burden of co-payments on patients. “Counties Manukau, the DHB will refund all part charges,” says Marlow, the women’s ultrasound specialist. “There are no part charges because they found that it was an equity issue and a barrier to care. And so that’s unique to that region.”

“Counties Manukau Health decided in 2017 to support pregnant people who were unable to afford the co-pay, as it became aware that some pregnant people were not attending routine scans due to the charge,” a spokesperson from the DHB confirms. “We believe Counties Manukau Health was the first to do this, reflecting the need for equitable outcomes and recognising the level of economic need in our community.”

The level of need in the area is high. The DHB “provides maternity care for a population where 62% of pregnant people reside in quintile 5, the most deprived socioeconomically; 20% of births are to Māori, and 31% to Pasifika families,” the spokesperson continues. “Counties Manukau Health area also has the highest perinatal mortality rate in New Zealand.”

So, recognising that ultrasound scanning is “a vital factor in complete maternity care,” Counties Manukau DHB made the decision to fully fund it. The Bay of Plenty DHB followed suit last year.

In the Auckland DHB catchment area, where Ascot Radiology operates, there’s no additional public funding available beyond the $80 provided by the Ministry of Health, Rogers says. This helps explain why a pregnant woman in Counties Manukau can avoid co-payment charges from private providers in her region, while another woman living slightly further north in the Auckland DHB area is likely to encounter co-payments exceeding $100.

When asked why Auckland DHB doesn’t follow in the footsteps of Counties Manukau, a spokesperson tells me that “DHBs have to make difficult decisions on where to direct the funding they receive from the Ministry of Health each year.”

“We understand that co-payments may be a barrier for some women to access obstetric ultrasounds,” the spokesperson says. “We’ve made the Ministry of Health, as the funders of primary maternity services, aware of this potential barrier for some women in our community.”

If pregnancy scans are so expensive, can’t women just opt out? Well, yes, they can: as with medical care more generally, ultrasounds in pregnancy aren’t compulsory – although not all women are told they can forego scanning. “It was never framed as an optional procedure,” says Clea, a 37-year-old communications advisor from Wellington who has had two babies in the past four years, both of whom were in the breech position and required regular growth scans. “[It was] always, ‘We have X concern about Y, and you’ll need a scan around X date to check the breech position, baby growth or uterus scar tissue.'” Clea’s scans cost her $600 across the two pregnancies.

More to the point, though, many expectant parents don’t want to opt out of the scans, and shouldn’t have to for the sake of cost: apart from the fact that these ultrasounds can be emotionally rewarding and reassuring, they’re also medically useful; sometimes critical. “If you’ve got a baby with a heart defect that requires surgery shortly after birth and you can identify it [at the 20-week anatomy scan], the woman and her family can get used to the idea,” Marlow says. “They get counselling, they know about it before the baby’s born, and we can deliver in Auckland, and then the baby will get really safe care and get the surgery within the first week of life.

“Whereas if you didn’t know about that heart defect and [the baby] was born in Wellington or at a secondary hospital, and we don’t know about that heart defect until that baby becomes critically ill, then you don’t have as good an outcome for that child,” she continues. “And that affects its long-term life, it’s not only at that point in time.”

So these scans can be a matter of life and death, then? “Yeah, definitely,” Marlow replies. “Scanning changes the face of maternity care … It’s part of the reason why obstetric care is so safe nowadays.”

Rogers, the radiologist, points out that 10% of women and 10% of children used to die in childbirth. “Ultrasound has been part of the equation that has contributed to reducing those numbers to [the point] where it’s rare to see a maternal death,” he says. “There’s a huge volume of literature that shows the cost-effectiveness of ultrasound scanning without even considering the positive effects of maternal bonding and [women] understanding their pregnancy and all that sort of thing.”

“It’s disappointing to see that the department of health values it so poorly,” he adds.

For Rebecca, Charlotte, Jay and Clea, the cost of scanning was annoying rather than prohibitive, but for some families, it’s the latter. “Maternity care in New Zealand is free so that barrier of [a] $45 [co-payment] – the women can’t afford to pay so they are not attending their scans,” Ōpōtiki midwife Lisa Kelly told RNZ. “They’d rather spend the money on paying bills and putting food on the table.” Ultrasound scans can involve collateral costs, too, such as time off work and travel to and from the clinic. This can be especially burdensome for people living in rural areas, where the nearest ultrasound clinic might be in a different town.

“The Ministry [of Health] acknowledges that these costs can be a barrier for some people to access healthcare,” Perry says, echoing the Auckland DHB spokesperson. The ministry’s position, she adds, is that “all pregnant women/people should experience equitable access to high quality, clinically-appropriate maternity ultrasound services.”

But where, practically speaking, does this statement leave families who would find a bill of $475, or even $45, prohibitively expensive?

Perry notes that “some providers may choose to reduce or waive their charges for those with a Community Services Card,” although she confirms there is “no legal obligation for them to do so.” She adds that the ministry is “working to implement the recommendations of the Maternity Ultrasound Advisory Group to improve access and increase the quality of community maternity ultrasound services.” To do this, the ministry is “exploring the MUAG recommendation that co-payments should be removed.”

Marlow would be thrilled by this development. “We would love our clients just to come and not have any part charges,” she says. “That would be our dream. And I know that there’s other providers that feel that way, too.”

So will the Ministry of Health walk the walk by increasing funding? “Any changes to public funding for health services which require further investment will be considered alongside other priorities within the health system,” Perry says.

While the ministry considers its priorities, expectant parents will have to bear the brunt of sometimes hefty co-payments – which, again, often come as a shock given the presumption that maternity care is free. Without relief from these costs, and particularly as the cost of living soars, the ability to monitor your baby’s growth and development – and share those cute scan images – risks becoming a luxury good in Aotearoa.