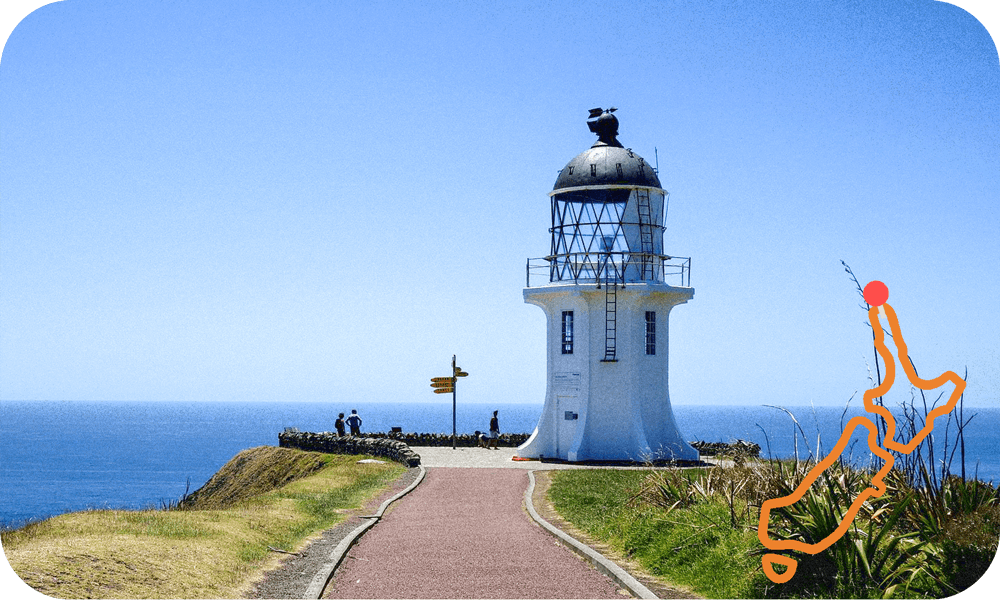

In this story from the Electric Highway, Don Rowe heads to the Far North to learn how Ngāti Kuri are keeping an eye on the future.

It’s a long way to the top, and nowhere is that more true than here in Aotearoa. For most of my life I had a mental image of the upper North Island as Auckland, Waipu, Whangarei and then… something. But having spent a little more time in the Far North, it really is an astoundingly vast region and every bit as beautiful as the mountainous south. And incredibly, just 20km from the tip of the country, the ChargeNet network has EV drivers covered at Te Hāpua.

For the past two summers, Ngāti Kuri has taken over management of the area. From the campground at Kapowairua, to the dunes at Te Paki, to the sacred Te Rerenga Wairua, Ngāti Kuri’s kaitiaki manaaki the thousands of manuhiri who journey to the place where the Tasman Sea meets the Pacific Ocean. They look like rangers in their utes and khaki, but the hospitality is taken very seriously.

This story from the Electric Highway is brought to you by BMW i, pioneering the new era of electric vehicles. Keep an eye out for new chapters in Don’s journey each week, and to learn more about the style, power and sustainability of the all-electric BMW i model range, visit bmw.co.nz or click here.

For Reg Lelievre (Ngāti Kuri), who returned home to help manage the campgrounds in 2019, going back to the whenua was a revelation. “I never, ever thought I would come back here. I was a city boy hard, living in Auckland and loving the dollars. Now I just can’t believe I was so stupid.”

The campgrounds help fund Ngāti Kuri’s conservation work in the Far North. The area is rich in endemic species and a partnership with Auckland Museum means scientists and botanists are regular guests in the rohe.

“There’s stuff up here that you just don’t see. And so they’re very keen, as are we, to make sure those taonga are retained and don’t get lost – or eaten. They all need special attention, which is what this is all about. These endemic species in the Far North are taonga that we are really keen on looking after, to make sure that they don’t disappear.”

Ngāti Kuri also brings in tamariki from kura across the rohe to learn about conservation, water quality and the local ecology, laying the groundwork for the next generation of kaitiaki. “It’s all about the kids, they are the future. We’re gearing them up and getting them onboard before it’s too late for the lot of us,” says Lelievre.

“And these kids know the area, they hunt here, they were brought up here and they know the place like the back of their hand. They don’t need to be DOC rangers, they already know where these key places are, they just need the funding and tools to do the job. They’re perfect for it, who can look after a place better than your own people?”

In te ao Māori, Cape Reinga/Te Rerenga Wairua marks the place where Māori spirits descend into the underworld along the roots of an ancient pōhutukawa. They emerge at the Three Kings Islands, looking back from Ohaua, before returning to their tupuna in Hawaiiki-A-Nui. The place is silent but for the roaring of the wind and the waves. Out to sea, the huge tidal forces create whirlpools and rapids.

New Zealand’s trail, Te Araroa, starts here. And for some unprepared hikers it ends here too, on the endless stretches of sand. Kaitiaki from Ngāti Kuri sometimes find them, I’m told, burned and dehydrated, victims of the merciless heat and sun. There’s not much phone reception and the whenua retains an element of the frontier, that special sense of timelessness you find in places like the East Cape.

With the BMW iX parked up at Te Paki, I set off to climb up the famous dunes of golden sand. And up, and up, and up. Size and distance seem to lose meaning there, the true scale of the place distorted like the mirages which hover above the ground. Operators in the area rent boogie boards for tourists to slide down on. I borrowed one and, being mindful not to “scorpion” my way to a broken neck, zipped down the tallest dune I could find. The exhilaration was equalled only by my despair at then having to walk the board back up to its owner, waiting at the top.

I’d bought a fishing rod on the drive north. I’ve never been much of a fisherman, something I’ve always chalked up to a lack of patience and ignoring all the sage wisdom like “it’s not about catching fish”. But it certainly felt like it was about catching fish at Kapowairua, as schools of kahawai swam back and forward just metres off the rocks, oblivious to – or disgusted by – my offerings. It’s one thing to plumb the depths, waiting for the sweet rush of a bite, oblivious as to what lurks beneath. It’s another kind of hell entirely to see the fish in their hundreds, taunting you with every shimmering scale.

And then, ecstasy. The line went taut and the fight began. Man versus fish. It had to be huge, a leviathan, some primordial beast. I slipped about in my Birkenstocks, tripping over half-frozen bait and narrowly avoiding the $2 kitchen knife and chopping board containing my tackle. On the same beach where Celebrity Treasure Island was filmed, I felt like Chris Parker, only without the talent or charisma. Was it a record-breaker? Maybe not, it was a reasonably juvenile looking thing. But it was mine.

I took it back to camp, where Ngāti Kuri’s kaitiaki live during their shifts in a compound of portacoms and big canvas tents.

“Tangaroa was good to you, my bro,” Lelievre said “This fulla has been persistent, I’ll give him that.”

Lelievre taught me how to fillet, and then wrapped the fish in newspaper – it wasn’t much of a contribution, a bit of manky kahawai in a bounty of crayfish, smoked mullet and wild beef the kaitiaki had prepared. We spoke deep into the night about the history of the area, about the tupuna interred on the hill and the spirits the locals say frequent the empty beaches at night.

The Far North is the kind of place that stays with you, a place where manaakitanga is still a way of life. Kapowairua is an appropriate name – the whenua is thick with wairua. And so while I drove south in the iX, with my kahawai on ice in the back, I took more with me than fish.

“You leave knowing what we’re all about,” Lelievre told me later. “It’s very cool. It’s very empowering.”