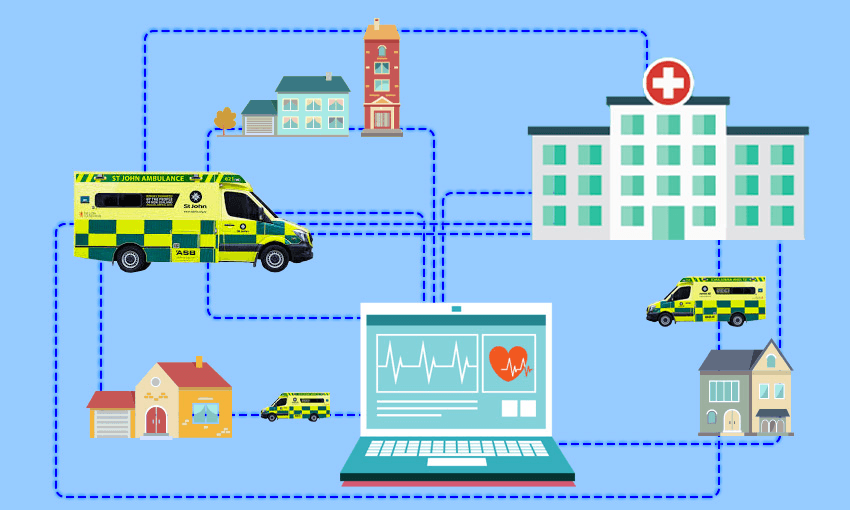

Technology has the potential to save the lives of communities with health issues, as long as it isn’t to hard to use. Ben Fahy learns how St John is using the Internet of Things to respond faster and better to emergencies.

In March this year, the day before Aotearoa first went into Covid-19 lockdown, St John New Zealand deputy chief executive Pete Loveridge was regaling an audience with tales of his organisation’s experience with the Internet of Things (IoT). After recounting an entertaining story about the time his smart toothbrush told him he had poor brushing technique – an example of the ‘Internet of Pointless Things’, in his words – he played a video featuring a man named Terry, this time illustrating what Loveridge calls the ‘Internet of People’s Things’.

Tears welled in Terry’s eyes as he talked about the time he fell over in his kitchen and was unable to reach the phone to call anyone for help. According to Loveridge, 93% of elderly people don’t want to move out of their own homes. Terry was among that number, but after that accident, he wasn’t sure he could remain there. He needed to feel safe, and his loved ones needed to know he could get help if he needed it. A St John medical alarm was the thing that gave everyone the confidence required for him to stay – and the thing that gives the organisation’s team the opportunity to ask the question that matters most to them: are you OK?

Loveridge admits that previous iterations of the alarm system were a bit on the bulky side, but function beats form in this context: more than anything else, the device needed to be bulletproof and work every time. He’s seen too many hardware peddlers offer him shiny new solutions that end up being too difficult for older people to install, need charging at night (when his customers are more likely to need them) and require another set of software for his own team to install and integrate.

Spark’s IoT business development manager Matt McLay has been with the company for 22 years and has been working with St John since 2001. He says that choosing a favourite example of IoT in action among its customers is like choosing a favourite child, but St John stands out both for the tangible benefits that connected devices have had on its customers’ lives and for how the organisation has used continual experimentation to improve the way it works.

The alarms themselves used to rely on the customer’s landline to call out if there was an emergency, which meant users had to stay fairly close to the physical hub in their home. The newest version of the alarm, however, takes the form of a medallion that can be worn around the neck, which stays charged for up to a month and communicates primarily through the cellular network (with the landline used as a back-up). Launched three months ago, this new technological step means that customers can press a button and talk through the alarm unit to the contact centre.

McLay sees the upgraded device as an example of the mobile network doing what it says on the tin: increasing mobility. Users might now have renewed confidence in mowing the lawn, spending time in the garden, or getting out into their community. For Loveridge, it’s another great example of his ‘IoPT’ in action; balancing technology with human interaction, and delivering tangible and meaningful results.

Each to their own

One of the most challenging aspects for St John is in its demographic: many of its customers have lower technology literacy, so newer solutions may not actually be the most effective – or may encounter resistance.

Voice-activated technology may seem like an obvious answer here, with people able to ask their smart speaker to call in an emergency. But Loveridge says its trials with Amazon Alexa in customers’ homes showed those who were less tech-savvy or who had age-related memory issues tended to forget the name of the device and how to access it.

“They need a card above Alexa to remind them,” he says, which is not too helpful in an emergency.

While Loveridge certainly isn’t anti-technology, his work has shown him some of the blindspots of the people who develop it – and the lengths some will go to make sure they walk a mile in their customers’ shoes. St John is currently working with a company that has developed a tablet device to check on elderly customers’ health. It works straight out of the box and syncs easily with other devices, but St John also had its developers wear glasses with Vaseline smeared all over them and said “try to operate this tablet”.

“Because that’s what it might be like for someone with early signs of cataracts,” Loveridge says. And the lesson is that you need to closely observe customer behaviour and design appropriate solutions for your specific market.

Taking the initiative

Medical alarms are, by design, a reactive technology. If someone falls over and is stuck on the ground, they know they can push a button and get help (although another quirk of St John’s customer base is that some customers, including McLay’s grandmother, have spent the night on the ground after a fall, simply because they didn’t want to push the button and disturb anyone at night). But in some cases, its alarms are starting to be activated automatically. The organisation is currently working with EROAD, a company that monitors fleet vehicles, to install devices that can alert St John dispatchers automatically if a crash happens. Monitors worn by lone workers in remote areas can do the same.

But rather than just responding to events that have already happened, the next step is trying to stop accidents from happening in the first place. Ultimately St John want to move from a reactive to a more pre-emptive model, and to use their technology to try and keep people healthy.

“We’ve been quite lucky to do a proof of concept with St John,” says McLay. “The question was: what else could we monitor in the home? Is there a ‘normal’ that we can assess, so that when something is abnormal, we can detect it and respond? Is there a possibility of early intervention? That’s our aspiration and it’s definitely on our roadmap.”

Initial options could include things like the temperature inside the house and sensors that can detect movement (or lack thereof) so if anything is awry the team can do a welfare check. In time, Loveridge says they might even be able to see if a customer’s behaviour changes after they’ve taken some medication, so they could get in touch and ask them how they’re feeling.

Doctor, doctor, give me the news!

For those of us who have embraced the quantified self and allow ourselves to be constantly monitored, the future of health is looking much more precise. The latest Apple Watch can take an electrocardiogram and notify you if there’s an anomaly that should be checked out. And a number of companies are making smart devices that can measure things like heart rate, body temperature and sleep quality, as well as things like cortisol levels for signs of stress or body fat percentage. These trackers work out what’s healthy for you, and then, if the data goes outside those boundaries, alert you to the issue. Some even believe that a wave of connected ingestibles will also offer better information about individual patients and their insides, so their treatments can be more personalised.

As with all the best IoT solutions, the more you know the better. And as these systems collect more data, the more adept they’re getting at providing insights. But given that health data is more sensitive than, say, information about your favourite colour setting on the smart lights, McLay says security is even more paramount.

“It’s a foundation of what we have to build. But this is an access point to your network, so you need to think about what info bad actors could get hold of and how they could use it.”

Home is where the heart is

While St John and Spark are looking to monitor homes for accidents, the big tech players’ investments into IoT platforms and their ongoing battle to dominate our homes is also making us more comfortable and efficient.

McLay is an Apple HomeKit advocate and says his phone is able to tell his home that he’s on his way. He’s set up rules for the air conditioning and lights automatically, and he gets notifications if the security cameras detect movement in the home. Perhaps best of all, it was relatively easy to set these things up.

“In the past you had to pay people a lot of money to install these kinds of products,” he says.

But McLay also sees potential for IoT and monitoring to improve our health at work. After a day of breathing in our mostly full offices, how much CO² is in the air? If it’s a bit too much, could the afternoon slump be avoided with a bit more oxygen? How many unhealthy particulates are in the air (and how many more dangerous toxins might be floating around after the work Christmas party)? If you know that people have different preferences for temperature and lighting in different areas, how can you tweak conditions for specific locations or at different times?

McLay defines his role as listening to customers’ problems and bringing what he has in his kitbag or using what’s worked before for other customers. He admits that it’s taken a while for the IoT to prove itself, but after years of experimentation and some major investment into networks, things just work now: the battery life of devices is improving and the cost is decreasing; the connectivity is more reliable, even in more remote areas; and organisations – and individuals – are starting to figure out what information is valuable and how they can change their behaviour based on the insights they’re getting.

Like Loveridge, McLay says Terry’s story has really stuck with him. He passed away a few years ago, but his family agreed to let St John continue to tell his story in an effort to convince more people like him that the technology could enhance their final years.

Terry’s alarm let him remain in the place he felt most comfortable. The next iteration of the alarm will give people like him even more freedom to move about the world with confidence. And in the future, the monitoring technology on us, around us and possibly inside us will learn what’s normal and intervene when necessary.

“We’re all going to benefit from this,” says McLay. “For me it’s a really exciting time, because the hype now actually matches the reality.”