Disruption during a traditional Welcome to Country at Melbourne’s Anzac Day dawn service has revealed the grim state of race relations across the ditch, writes Ātea editor Liam Rātana.

It was 5.30am on Anzac Day. The sky was still dark, but 50,000 people had gathered at the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne to honour those who served – including the estimated 5,000 Aboriginal soldiers who fought in the first and second world wars.

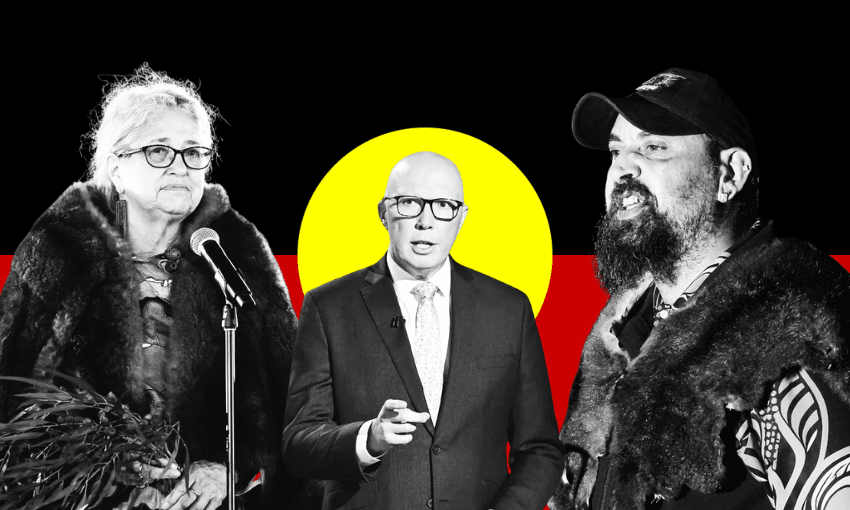

Draped in a traditional possum fur cloak, Bunurong elder Mark Brown stood in front of the podium to welcome the crowd to the land of his ancestors. As he began speaking, a small group of hecklers attempted to interrupt Brown with boos and negative comments. “What about the Anzacs?” one of them shouted. “Don’t welcome me to my own country.” Despite the attempted interference, a defiant Brown continued with his welcome, being met with applause from others in the crowd.

That evening, local NRL team Melbourne Storm was set to play in a highly anticipated match in front of 26,000 fans at a sold-out AAMI Park. To start proceedings, Wurundjeri elder Joy Murphy Wandin had been invited to provide a Welcome to Country to start the Anzac Day ceremony.

However, following the morning’s events and subsequent controversy, Murphy Wandin was told she would no longer be required as the Welcome to Country was cancelled. “The board doesn’t feel comfortable having a Welcome to Country because of what happened in regards to the booing of Uncle Mark Brown at the Anzac Dawn Service,” is what the Djirri Djirri dancers, who were meant to perform following the Welcome to Country, allege they were told. Murphy Wandin said the Storm then reversed its decision before its chief executive Justin Rodski allegedly cancelled it again. This was despite Murphy Wandin already being at the stadium and having completed her final rehearsal.

Subsequent reporting has revealed that Storm director Brett Ralph is a significant donor to right-wing lobby group Advance, which is actively campaigning to end the practice of Welcomes to Country around Australia. The Storm have since released a statement claiming the cancellation was due to a “miscommunication of expectations regarding the use of Welcome to Country at Melbourne Storm events” between the club’s board and management. It is alleged the board were unaware that a Welcome to Country was to be performed at Friday’s game.

The Welcome to Country is not a new practice. As Aboriginal Australian education leader Jessa Rogers recently wrote, “Welcome to Country is a sovereign Aboriginal protocol, grounded in the laws, customs and practices of First Nations that have existed on this continent for tens of thousands of years”. A Welcome to Country is conducted by an elder, a formally recognised traditional owner, or a custodian, to greet visitors to their ancestral land. The ceremony can vary in form, often featuring a speech, traditional dance and a smoking ceremony.

The practice saw a modern renaissance in the late 1970s, following a Welcome to Country performed by Yamtji men Ernie Dingo and Richard Walley, for a group of Aotearoa Māori and Cook Islands Māori attending the Perth Fringe Festival. It is widely believed to be one of the first recorded welcomes for a group of people not indigenous to Australia.

In 2008, the official opening of Australia’s federal parliament began with a Welcome to Country for the first time. It has since become a standard feature. The day after, then prime minister Kevin Rudd gave a formal apology to indigenous Australians for the atrocities committed against them.

However, following the Anzac Day controversy over the weekend, the use of Welcomes to Country was thrust into the spotlight, highlighting deeper issues around race relations in Australia. On Sunday evening, during the final leaders’ debate prior to the Australian election, opposition leader Peter Dutton claimed Welcome to Country ceremonies were “overdone” and said their regular use “cheapens the significance”. It was an easy way for Dutton to score brownie points with the (probably small) sector of Australians that agree with him, much like the politicians here in Aotearoa who pander to a similarly small, yet vocal crowd.

The kerfuffle with the Welcomes to Country in Melbourne on Anzac Day made me sad. Sad for our indigenous brothers and sisters in Te Whenua Momoeā. Sad that they are still being met with such overt racism while practicing their cultural traditions, literally welcoming people to the whenua where they have lived for at least 65,000 years. Sad for my cousins, nieces and nephews who call Australia home. Sad that they are growing up and living in a land where some people still have such visibly little tolerance and respect for indigenous cultures.

While I am fully aware that racism is alive and well here in Aotearoa, I like to (perhaps ignorantly) believe that our race-relations are better than that of the country across the ditch. We don’t have people attempting to stop others from singing the national anthem in te reo Māori, or running on the field to stop the All Blacks doing a haka.

However, we do have several recent instances of intolerance for indigenous practices and beliefs here in Aotearoa. One such case is that of Kaipara District mayor Craig Jepson, praised by many of his constituents for banning karakia before council meetings. I also vividly recall a group of Pākehā verbally expressing their dismay at a karanga being performed for Lani Daniels’ entrance to her world heavyweight boxing title fight in 2023. “Just get on with the fight,” one of them said as she tsked and rolled her eyes.

Although I believe we are slightly more tolerant of, and educated on, the importance of Māori cultural customs in Aotearoa, I also think the select group of our population that is against the growing normalisation of these practices is becoming more galvanised in their beliefs. With that comes a growing inclination and comfort in publicly and explicitly expressing those views – not just on social media, but in real life too. My only hope is that we are quick to call out this harmful behaviour and continue to foster an acceptance of all cultures among our youth – especially of the indigenous culture of this land. One of the most important things to remember from this whole fiasco is children don’t invent racism, they learn it.