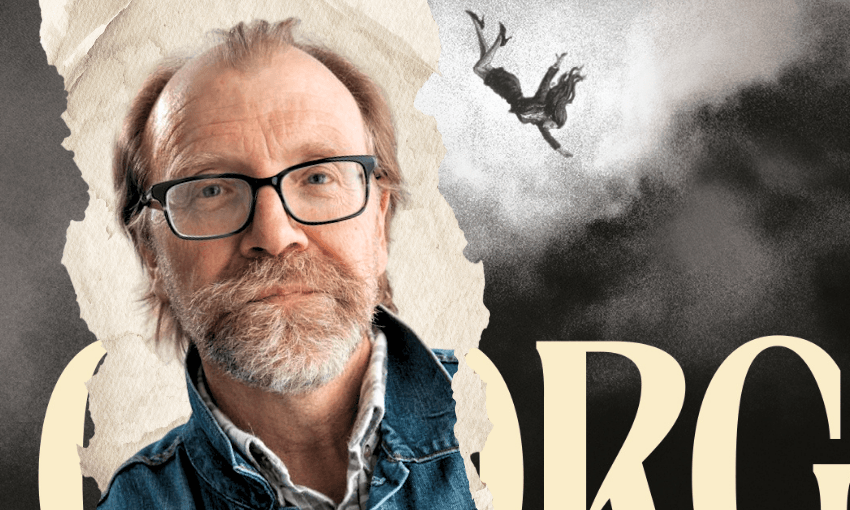

Books editor Claire Mabey talks with American writer George Saunders about his first novel in nearly a decade.

George Saunders appears visibly frustrated when I bring up the kindness thing. “I’m not any exemplar of kindness at all,” he says earnestly into the screen. “I’m quite snotty, at least in my mind. But it’s an albatross to be seen as the genial uncle of American letters.”

Saunders is worried that the proliferation of the idea that he is the purveyor of kindness is going to “take the fangs” out of his work. It started back in 2013 when he gave the convocation speech at his university – Syracuse, in New York. He told a story about a kid in his class who was teased, and how, 40 years later, he was still thinking about her because the nature of his regrets are tied up with failures of kindness. When the New York Times posted the text of the speech in full, Saunders’ words went viral and have been reiterated ever since.

Saunders’ new novel, Vigil, is an argument for how kindness can fail; how wrong-headed kindness misapplied at the wrong time is futile. It’s a novel that deliberately tests the patience of its readers and shares the same fascination with that liminal space between life and death as his Booker Prize-winning first novel Lincoln in the Bardo. Vigil is quintessential Saunders: theatrical, dark, funny, inventive and, ultimately, a morality play wrestling with an ambiguous thesis.

When I tell Saunders that I was stressed by his winningly benign main character – a ghost called Jill “Doll” Blaine – he beams, reassuring me this is precisely as hoped. Jill is a death doula, charged with ushering the dying into the next life, and has performed this task 342 times already by the time we see her plummeting, clothes materialising as she falls, to earth ready to “whisk” her way into her next gig: to helpfully haunt KJ Boone, ruthless oil tycoon and proponent of climate change denial, as he stews on his opulent death bed. Jill’s job is to soothe Boone in his final hours, slipping into the orb of his mind, probing for any signs of self-reflection: any regrets?

Nobody else writes quite like Saunders, but Vigil reads like Saunders in hyper-drive. It’s a black comedy with unmistakable influences of Monty Python and, in particular for this story, The Muppets’ take on Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. The cast of ghosts that dip (literally, through the ceiling of Boone’s bedroom) in and out of the story, disturbing Jill’s work, are quippy caricatures trapped in the inbetween by unfinished business. One pair of dastardly, now dead, colleagues of Boone’s blast in and perform a comedy act strongly reminiscent of Statler and Waldorf’s Marley and Marley.

Some of the antics in the novel surprised even Saunders, who is an improviser: he sits at the writing desk ready to discover what might happen as opposed to meticulously planning it out. It strikes me just how freeing the afterlife is for a writer engaging in high-stakes philosophical conundrums – realities that if grounded in realism could be dense, and earnest, as hell. In Vigil, Saunders’ ghosts are larger than life, falling in and out of the novel like Beckettian clowns tumbling in and out of the wings of a stage. In fact it’s hard not to suspect, at times, that the book was written with adaptation in mind. “If I sit down and go, this could be a movie – I like that feeling,” Saunders tells me. “Like with Lincoln in the Bardo, I always saw it on a stage. It helps me imagine it a little more vividly or something, or with a little more fun.”

While Vigil is dark, a climate crisis tale like no other, every one of its 172 pages is undeniably entertaining. The incorporeality of ghosts gives Saunders’ characters an athleticism that is a rush to experience: they fly like in dreams, traverse great distances in a blink of an eye, perform aerial acrobatics, and dive through solid matter. Saunders’ ghosts lend the bleaker narrative underneath a surreal absurdism as well as a startling brutality. When benign Jill “Doll” Blaine starts to remember her earthly life and how it was ended (terribly, dramatically), her ghostly self comes into a new, more vengeful power which culminates in a flurry of obscene and hilarious acts – one involving lacerating a ghost and filling it with concrete; another involving a very painful ghost shit.

“I love her,” says Saunders, smiling again. He was interested in writing a character born in the 1970s, longer dead than alive by the time we meet her. Jill existed before climate change was a crisis, and as such channels a sort of apolitical perspective. Without a full understanding of Boone’s impact on the earth it’s his true bad nature, rather than his acts, that begin to repel Jill, pushing her further into the past.

“I think [Jill] was disrespected a lot as a young woman,” says Saunders. “She’s of my generation – I saw that growing up – those subtle sexual jokes while at the same time it’s ‘Hey, y’all, will you go get me a coffee?’ You know, that crap.” Over the course of the book Jill’s life returns to her in heady fragments of language. The rush of memory – of embodied love and desire and disappointment – alchemises in ghostly Jill. Upon the confrontation of her (explosive) death, among other things, her two selves mingle and come into conflict. Jill tries to hold on to her blissed out “elevated” state by repeating, almost like a mantra, the idea of “inevitable occurrence”. It’s how she bolsters her empathy for bad guys, for sad guys. It’s how she gives comfort: “Be not afraid, I said. For you are inevitable. An inevitable occurrence.”

Saunders explains the concept to me through the analogy of his child self, who was good at reading and so felt sorry for a classmate who wasn’t. Should someone who had the “good at reading” box ticked before birth be guilty over it? And if not, how do we then treat other inevitabilities, like Boone’s propensity for power hoarding and destruction?

KJ Boone, like Trump, is inevitable. When one power-hungry psychopath dies several more will spring up in their dust. In this way, Boone is the novel’s least interesting character. It’s Jill we need to grapple with. And the fact that in this world the Jills vastly outnumber the Boones. Jill’s flaw, as was Boone’s overly edifying parents’ before her, is not to judge him. Where she could be rightfully hard on him she is soft; where she could be furious, she lets him off the hook with the inevitability argument.

The thing with Jill is that she’s not as good at providing comfort as she thinks she is – she’s too kind to be truly helpful. “Kindness, niceness is rampant here in America,” says Saunders. “As long as your voice is soft, you’re being kind. But in the Buddhist tradition in a given situation are you benefitting the person inside your orb?”

The orb is a central motif in Vigil. People and ghosts have orbs and when Jill slips inside one she can read thoughts, view memories. It’s an act of excavation that slowly but surely confirms that her latest job, KJ Boone, is irredeemable. So confident is he that he has lived a life in God’s grace that he welcomes the end in the boldest of terms: “Goodbye, beloved hunk of rock, overrun as late with jabbering moronic ingrates … Thank you, Lord thank you for making me who I was and not some little squirming powerless nincompoop.”

“I think the work I was doing was trying to let [Jill] make her case, trying to let [Boone] make his case, then also trying to split her into those two people who have a different outlook on judging him,” Saunders explains. The “two people” is Jill as rightfully angry woman, and the “elevated” ghost: almost literally lifted above human concerns, such as being offended and pissed off when a dying oil tycoon you’re meant to be helping calls you a “stupid bitch”. Saunders explains that in Buddhism there’s an “absolute realm” and a “relative realm”: Jill is sort of pinched between both through her encounter with the immovable Boone. Her human remnants want to judge him, but her elevated self suspects that we are all, as Saunders puts it, “part of this grand machine.”

“The book was, for me, just a journey of trying to build up both of those arguments to make them irrefutable, separately, and then let them bash their heads against each other,” says Saunders. “And yeah, maybe stress out.”

Vigil has arrived in the midst of out and out horror. ICE continues to terrorise civilians; Trump wields his power with horrifying hubris. Surely it is impossible not to judge this man, all those like him, in the harshest of terms? In light of Jill’s determinism, I can’t help but consider, too, Jacinda Ardern’s politics of kindness; the politics of radical empathy. Is that what the world needs right now? Or is there also room for rage?

Saunders is asking us to entertain the idea that we need both. That as we exercise our rightful rage we hold onto our elevated selves, too. The last thing we need is to lose humanity in the revolution.

Vigil by George Saunders ($37, Bloomsbury) is available to purchase at Unity Books.