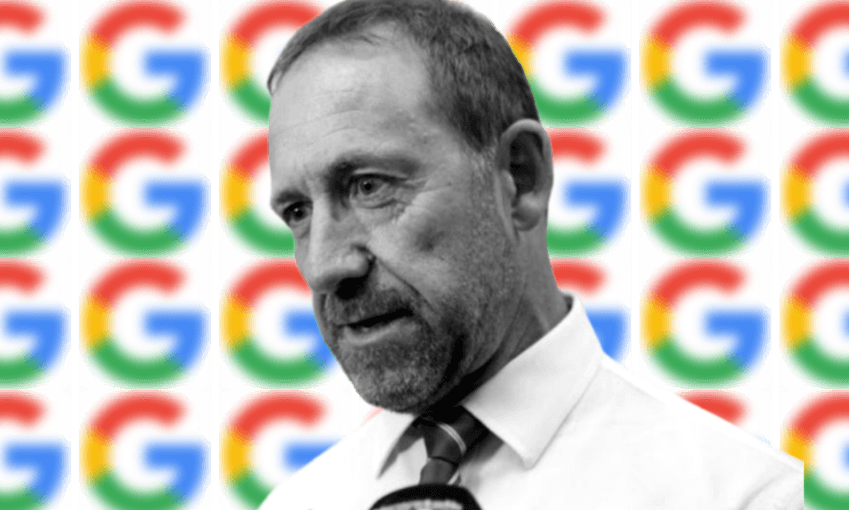

New Zealand’s minister of justice responds to the decision by the internet giant to take no action after its breach of name suppression in the Grace Millane case

Google’s attitude to fair trial rights in New Zealand should concern us all. It’s time to call out their recklessness.

To recap what happened, last year at the first appearance of the person accused of murdering British tourist Grace Millane, the judge ordered temporary suppression of the accused’s name. Google’s newsgathering algorithm picked up a British newspaper’s report of the court appearance, a report that breached the suppression order. Google’s system proactively alerted New Zealand subscribers to the report, and in so doing also breached the suppression order.

When I confronted New Zealand Google executives about what happened they indicated they took the issue seriously and would look at what they could do to fix the problem. Six months on, they now tell me they can’t – or won’t – do anything.

Permanent suppression orders are very difficult to get in New Zealand. But temporary, or interim, suppression orders are commonly used in the early stages of a case to manage the needs of a fair trial. They are used as a practical application of the principle of being presumed innocent until proven guilty.

Even at the time of arrest, or well before the trial takes place, there is a lot for prosecuting and defence counsel to do to prepare, including working out what facts or issues are in dispute. Sometimes the issue of identification of the perpetrator is in question. Keeping the identity of an accused secret until after the trial ensures witnesses don’t get confused between what they saw around the time of the offending and what they’ve seen in the news since.

I’ve taken Google to task over their publication of suppressed information. Frankly, their size, far from meaning they can’t fix an obvious risk to justice systems, means they are big enough to do better. I would be failing in my duty if, as a minister of justice in a small country, I threw in the towel and decided nothing could be done in the face of a giant international corporation thinking it could ride roughshod over one of the most important principles of criminal justice.

Google chooses to operate their business here, to earn revenue here, to publish news and information here. So they have obligations here. The same obligations other news publishers have. And for that matter, other multinational corporations.

I will not accept that Google can avoid their obligations. New Zealanders deserve better.

So I’ve asked for advice on our current suppression laws, the contribution of the Contempt of Court Bill that is currently before parliament, and what more is needed. I also want to know what avenues for legal action there might be.

This will be an issue that will affect other countries, so I want to explore how it is being dealt with overseas.

Meanwhile, one of the issues Google has raised is they don’t know what suppression orders are in force in New Zealand at any time. This doesn’t stop New Zealand based publishers from adhering to the law but I have asked the Ministry of Justice to review how it notifies media about suppression orders as part of its work to implement the new contempt laws.

One thing is clear. I’m not prepared to let Google off the hook, and all options are on the table.