As Aotearoa grapples with a reform of hate speech legislation, it could look to the other side of the world, and the case of a celebrated footballer, for inspiration, writes Ling Yee Wong.

Connecting Euro 2020 and hate speech via Marcus Rashford

What is discrimination? What kind of hate speech law can stop discrimination without restricting freedom of speech? These are all big questions but I think we can start small by thinking about one individual: Marcus Rashford.

Rashford is a very good football player. He plays for Manchester United, one of the most valuable football clubs in the world. In the 2019/20 season, he was the eighth top scorer in the English Premier League. He also played for England in Euro 2020 in June to July this year. England lost to Italy on penalties in the final. On the day, Rashford, along with his teammates Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka, did not score their spot kicks. However, most agree that Italy played better on the day and deserved their win.

Rashford is famous in England for another reason. When Covid lockdown first hit in March 2020, schools were closed and that meant children who relied on schools to provide meals would miss out. Rashford, having relied on these meals when he was young, decided to fill the vacuum and raised money to feed them and helped deliver the meals.

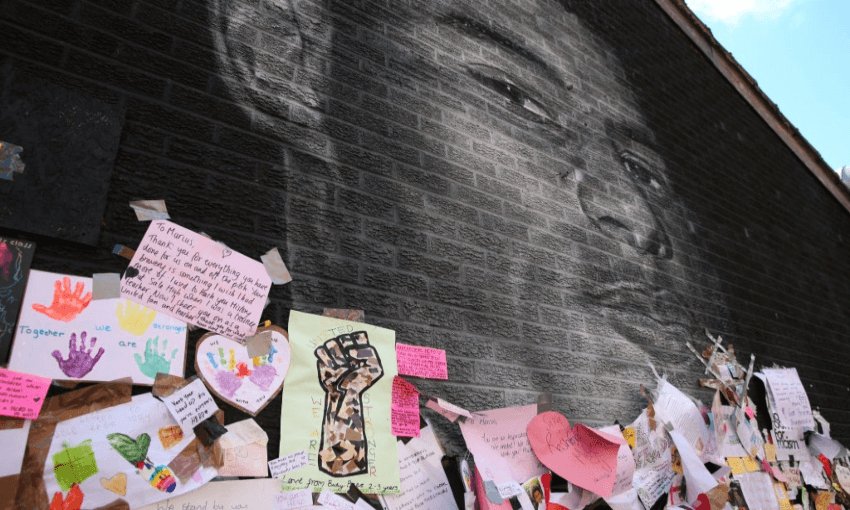

Despite his many charitable and sporting achievements, missing a penalty in the Euro 2020 final led to Rashford, along with Sancho and Saka, facing abuse on social media for the colour of his skin. Indeed the colour of his skin is hardly relevant to the ability to kick a ball under pressure, yet for his abusers that is the one characteristic they criticised him for: being black.

This is painfully familiar to anyone who suffers racism, sexism, religious discrimination, transphobia, homophobia, ageism, ableism, or any kind of discrimination. Nothing is good enough for those who intend to discriminate. If you are not good enough, it is because of your race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, etc — even when there is never evidence of a connection.

Hate speech law: criminal or civil?

In England, the police responded to the social media racist abuses of Rashford and his teammates with swift arrests. Under the Public Orders Act 1986 (UK) section 18(1), it is a criminal offence for a person to use threatening, abusive or insulting words if the person intends to stir up racial hatred, or in the circumstances racial hatred is likely to be stirred as a result. This could happen in a public or private place, with only one exception: in a dwelling where you have no reason to believe your words would travel outside (ie the my-house-my-castle exception). Social media is a quasi-public place and is not covered by this exception. There are equivalent statutes for inciting religious hatred, and these are the hate speech laws in England.

Compared with the equivalent hate speech criminal law in Aotearoa, which is the Human Rights Act 1993 section 131, the UK version in my view got one thing right: it sits alongside other public order offences like disorderly or offensive behaviour. In New Zealand, public order offences like disorder or offensive behaviour are criminal offences under the Summary Offences Act 1981. I am not trivialising the harm hate speech does, but I think the magnitude of harm of hate speech is similar to public order offences. What hate speech does is to make people apprehensive towards appearing in public: they make the relevant persons be afraid that they will be abused, when they just want to be left alone to go about everyday business. “It all adds up”, as Taika Waititi has explained. In other words, hate speech infringes the freedom to be left alone. Public order offences infringe the same freedom to be left alone. Imagine the typical drunkard’s disorderly behaviour on a Friday night, accosting all and sundry: such a person disturbs the peace and prevents other people from not being disturbed.

There is a lot of value judgement in determining whether a particular case is a legitimate exercise of free speech or hate speech. In my view JK Rowling provided an example of displaying transphobia without crossing the line into hate speech: you can see that there is an attempt to be polite, without intent to abuse. This is different from the kind of abuses that the law should be concerned with. The typical hate speech incident isn’t happening around anti-discrimination rally, or during polite debate, it is the random racial abuse on the way to the mall, or while on a bus, or sexist abuse on social media. People went out of their way to make abuses, and this “drive-by”, random nature of hate speech infringes the freedom to be left alone.

More important, this is similar to the kind judgement that the police has to deal with on a day-to-day basis regarding public order offences. Is a particular case of drunken behaviour not just annoying but disorderly? Is jogging nude an offensive behaviour? Police have to skillfully apply the law in any case, in order to balance one person’s freedom to be left alone with another person’s freedom of speech. When police got the balance wrong, the court will intervene.

In addition, in the twin cases of Brooker v Police and Morse v Police, the Supreme Court essentially has ruled that a serious case of disorderly or offensive behaviour, and recognised by an objective person as such, would breach the law, in order to respect freedom of speech as well. It is likely that any hate speech law would also be similarly interpreted by the court so only the most serious kind would be successfully prosecuted.

However, setting the hate speech threshold high does not invalidate the purpose of making hate speech law a criminal law. It would still allow police to respond immediately to incident of hate speech, and immediate response is probably more important to those suffering discriminatory abuse than convicting the abusers. If hate speech law would merely impose a civil penalty, any hate speech cases would have to snake its way slowly through the civil court. For example, Labour MP Louisa Wall’s civil complaint using existing hate speech civil law took four years to get through the court system. Most people, who are less determined or resourced than Wall would have given up well before then, as if there were no hate speech law at all – justice delayed is justice denied. Indeed the hate speech law in England, because it is a criminal law, allows the police there to swiftly respond to Rashford’s abusers.

Finally, let me point out that the exact definition of hate speech is clearly work-in-progress, though I have argued there are at least two essential elements: intent to abuse and intent to discriminate. Getting the definition right in the new legislation is paramount to prevent overreach, though I doubt any definition will ever cease to be a work-in-progress because free speech advocates will (rightly) contest its meaning.

Consultation on hate speech reform closes on August 6. You can give your feedback here.

I thank the assistance of Emma Burns in writing this article. However, all opinions or mistakes are my own.