Jacinda Ardern announced military-style awards to formally acknowledge the pandemic’s frontline workers. But a year on, hundreds of seemingly eligible people and organisations have been turned down, while around 50,000 awards remain unclaimed.

The early days of the pandemic were a blur for Terry Taylor. The president of the New Zealand Institute of Medical Laboratory Science (NZIMLS) spent his days liaising with the Ministry of Health, making submissions and dealing with the media. His sector was suddenly under huge scrutiny and pressure – its members handled the testing for Covid-19, discovering where the virus lay around the country. They were responsible for producing the number which functioned as a barometer of our national mood in those fearful days of April and May 2020.

Yet his work as NZIMLS president was a voluntary one, so by night he worked shifts at a lab, doing everything “from pre-analytical work to final reporting”. His team split into bubbles so as to avoid being knocked out as close contacts, and went into rolling shifts to ensure it operated 24 hours a day to cope with the scale of demand. This intensity never let up, he says, pointing out that while the rest of the health system had periods of lower strain during lockdowns, labs were under high load throughout.

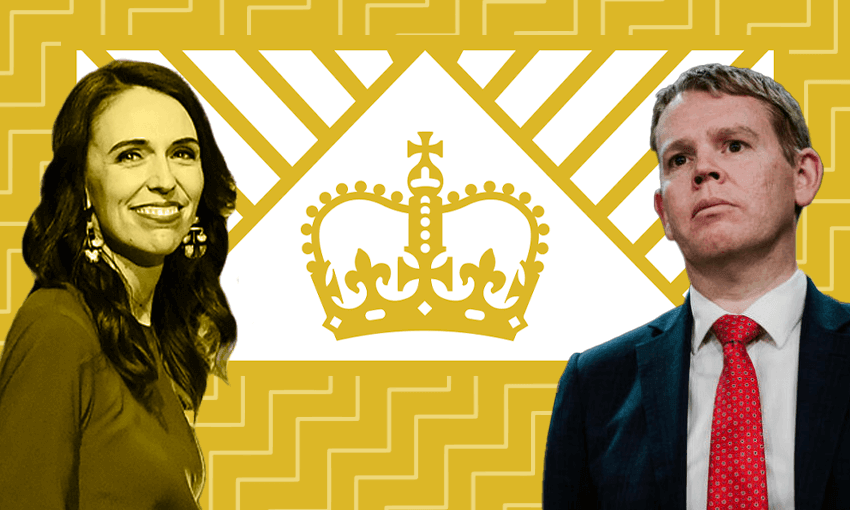

Almost three years later, Taylor reflected on that work when then-prime minister Jacinda Ardern announced the Covid-19 Response Recognition Award. The initiative was intended to formally acknowledge the service by thousands of ordinary New Zealanders during an extraordinary time. The award took the form of a certificate in the prime minister’s name and a lapel pin “in keeping with the likes of military service”, Ardern explained at the time. Provision was made for the manufacture of up to 80,000 pins, and Wellington-based metal design firm Mayer and Toye was selected to produce the pins at a cost of up to $2 million.

On the face of it, this was a beautiful gesture, something which wrapped up the “be kind” doctrine of Ardern’s leadership with the unified call to serve which typified the early stages of the pandemic. By the time it was announced, we were on the other side of the parliamentary occupation, so we well understood how much the national mood had soured. But the award, with its emphasis on frontline workers, seemed a pointed effort to acknowledge those who had helped protect the team of five million. Unfortunately, like the pandemic response as a whole, an initial clarity of purpose would later dissolve into rancour and discord.

The first group made eligible were managed isolation (MIQ) workers, in March of 2022. Later, the remit was significantly expanded in an announcement made on December 31 of last year. Those eligible included border workers, contact tracers, healthcare staff, vaccinators – and the Covid-19 testing workforce. The new year’s timing only added to the sense of a solemn, official acknowledgement of a national mobilisation which required a whole-of-society effort typically associated with war. Despite the eligibility being expanded, Ardern was at pains to retain the award’s focus. The statement announcing the changes singled out individuals and organisations “whose roles were particularly critical”.

Taylor read the reports and felt pleased that the work of the NZIMLS would be recognised. He says that the Ministry of Health had little experience in pathology when the virus struck, and that his volunteer organisation became a crucial conduit between it and the medical lab sector. He sent off an application, and looked forward to sharing the good news with his colleagues.

‘Your organisation does not meet the eligibility criteria’

A little after 1pm on Monday May 15, Taylor received an email. “Unfortunately your organisation’s application has been unsuccessful,” it read. “We know there was a lot of hard mahi done by so many throughout the Covid-19 response and while we would like to be able to recognise everybody, this award is for those who were on the frontline of the response or directly made the frontline possible.”

He was deeply disappointed. “My heart sank. Not for me, but for the other guys on the council. They put in thousands of hours with no financial compensation.” He was also far from alone in having his application declined. Overall figures are not available, but The Spinoff has been supplied figures from two key ministries involved in allocating awards which illustrate how contentious it has become. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) said as of May 8, 503 of 3,997 applications for the individual award were turned down, greater than one in 10. The numbers for the organisational awards are less favourable still, with 39 of the 129 applicants declined, a little over 30%.

Te Whatu Ora managed applications for the health sector. Chris Scahill is in charge of the awards there, and said in a statement that it issued just 254 awards out of the 575 applications received. While Scahill says that many were declined due to being “teams that applied within an organisation that was already receiving the award,” others were declined due to eligibility. Of more than 8,000 applications for individual awards, he says “more than 6,000” have been approved – implying thousands have been declined.

There aren’t figures for numbers declined overall, but The Spinoff has seen a large number of people sharing emails declining their applications. For those turned down, it can feel bitterly disappointing – like a diminishing of their pandemic-era effort, or a judgement on the importance of their work when set against that of others.

Gavin Hooper-Newton says he was turned down despite establishing eight drive-through mass-testing centres and over 120 vaccination sites. When he posted about his application being declined, a half-dozen other workers from different parts of the emergency health response replied, indicating that they or their colleagues’ applications had also been rejected.

Rob Hallinan of Te Whatu Ora Canterbury wrote that his part “in a staffing team that filled over 5,000 shifts [wasn’t] deemed as work that supports frontline staff”. Gertrude Agbozo wrote that she “worked on the All of Government Covid Response… I didn’t qualify”. Pam Oliver was part of the NZ Defence Force seconded to the response, but was also declined. “I guess working in MIQ facilities for two years, getting the border management clinical software system running in MIQ… swabbing Covid patients and looking after them in an MIQ facility, vaccinating border workers etc isn’t quite frontline?”

The winners and losers

Others who worked less directly within the response have proudly posted photos of their pins and certificates. These include those working for contractors installing IT equipment within MIQ facilities, aviation security analysts and the GM of growth at a company which supplied air purification systems.

While some, including Hooper-Newton, have ultimately been told that they will receive their award, the process has felt capricious and haphazard. Others found the process of having to nominate yourself off-putting, particularly when it ended in a declined application. For those who have successfully fought being declined, the most effective way to have a case reconsidered has often been to make a public statement on a social media network.

The issue seems to have arisen from the over-complicated process for determining eligibility, and the deliberate decision to exclude certain parts of the pandemic response. “The Award was primarily for frontline workers, not policy staff or those in senior leadership roles,” a staffer from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC), the government department which administers the award, said in a statement. The scale of the awards and hard-to-define criteria meant variable standards were near inevitable.

It’s been further complicated by just how many entities are involved in adjudicating. There are nine different ministries or agencies making calls on the individual awards, rising to a dozen for organisational awards. Shayne Gray, GM of MIQ at MBIE, supplied a statement explaining the slightly convoluted process. “DPMC are the lead agency for the Covid-19 Response Recognition Award, including the design and supply of the certificate and pin. Agencies, such as MBIE, were responsible for the delivery of the award to their respective workforces.”

In fairness to those making decisions, rendering such judgements at scale is difficult – especially without specialist staff or allocated funding. Further complicating matters is that during the pandemic many staff operated outside their titular roles, with the DPMC noting that “some people who met the criteria for this award may have been in a frontline or operational role during the pandemic, but not as part of their regular job.”

This made those vetting applicants into quasi-investigators, tasked with passing judgement on people’s contributions to the pandemic – a period of unique stress, and highly loaded with emotion for many New Zealanders. The distributed nature of those judgement calls likely explains why eligibility has become such a tense topic among those who worked under huge pressure during the pandemic, only to find themselves deemed unworthy by an anonymous government staffer.

It’s also puzzling to be so precious about what is ultimately a made-up award when so many remain unclaimed. Latest figures supplied to The Spinoff show that even after the proactive allocation of thousands of awards, just 20,000 individual and around 3,700 organisational awards have been distributed, leaving around 55,000 of the projected 80,000 unallocated.

Ultimately it’s meant that an award designed to recognise the contributions of those on the frontline has ended up causing hurt and frustration from many it was seemingly set up to honour. Instead of erring on the side of ruling line calls in, some officials seem to have chosen to exclude many whose experiences would seem to make them prime candidates.

Taylor’s feelings typify those of many who were passed over. He says his volunteer organisation contributed thousands of unpaid hours to the response, and now believes the pins are symbolic of a broader lack of recognition for the work of him and his colleagues.

“It’s like we got thrust into prominence for a while, when everyone saw our value,” he says, “but then just as quickly shoved back in the closet as we tried to forget the pandemic.” For Taylor and many others like him, there’s a bitter irony in the way an award designed to recognise their service has ended up feeling like it erased their work from history.