The rightwing enthusiasm for authoritarian Singapore illustrates the extent to which, on one crucial point at least, New Zealand’s hands-off approach to the economy has failed, argues Max Rashbrooke.

In years gone by, New Zealand’s right-wingers had predictable heroes. They looked to tax-cutting, regulation-shredding leaders like Margaret Thatcher, and their exemplar states all had libertarian characteristics: America’s weak trade unions, the former Soviet Bloc’s flat taxes, Ireland’s corporate-friendly “Celtic Tiger” economy. Now, though, a new hero has roared into view: Singapore.

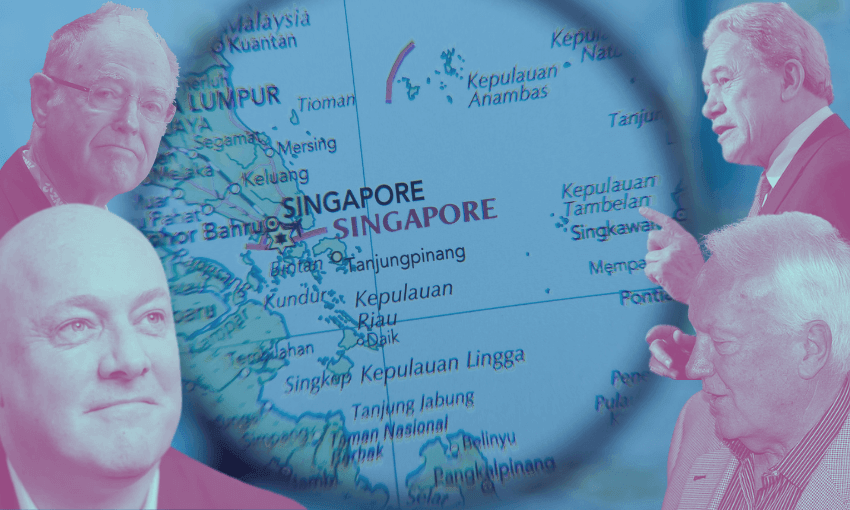

This interest dates back at least as far as a 2016 paper by Act founder Roger Douglas and Auckland University economics professor Robert MacCulloch, which lauds Singapore’s health and welfare services. But it’s everywhere now. “I’m a big fan of Singapore,” former National leader Don Brash said during a recent debate. Singaporean-style ideas turn up in New Zealand Initiative presentations. “Christopher Luxon hankers after Singapore’s success,” the Listener columnist Danyl McLauchlan wrote recently. Winston Peters’ mooted national infrastructure fund has parallels with Singapore’s Temasek.

It is, on the face of it, a strange enthusiasm. Far from being libertarian, Singapore is an immensely authoritarian state, one barely qualifying as a democracy. Since 1959 it has been ruled by one party, the PAP, which currently controls 89% of seats in its parliament. Political opponents are forced into exile or bankrupted by PAP “defamation” lawsuits. Similar tactics are used against journalists. Activists are jailed for holding up pictures of smiley faces.

Some right-wingers are, of course, happy to overlook such trivial matters as long as a government follows other parts of the conservative playbook. You could call it the John Key doctrine, given the latter’s support for Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro: the vilest behaviour, the most brutal assaults on human rights, can be justified as long as you cut taxes. (In fairness, parts of the left have long been willing to overlook parallel failings on their side.) And Singapore does indeed have low taxes and minimal restrictions on foreign investment. But its popularity on the right seems to stem from the other part of its somewhat schizophrenic approach to government: its unashamedly “big state” tactics for creating growth and promoting social outcomes.

Central, in both cases, is the push for greater savings and investment. Singaporean workers must put a startling 21% of their wages into compulsory savings accounts, and employers contribute a further 16%, sums that would otherwise be paid as wages. From these accounts, workers pay for their own pensions, healthcare and medical insurance.

This approach, Douglas and McCulloch argued in a 2016 paper, encourages consumer choice, limits health costs and provides high-quality care. Their paper exhorts New Zealand to slash state spending and force people to save, Singaporean-style, for not just their pension and healthcare but also for six months’ worth of “unemployment insurance”. Nor is it just Douglas and MacCulloch: a New Zealand Initiative researcher, Max Salmon, espoused similar ideas at a Retirement Commission event earlier this year.

Although I did, in the spirit of open debate, commission MacCulloch to rehearse these arguments for a journal I edited in 2019, I can see serious defects in this plan. For one thing, higher-paid people would get bigger pensions and be able to buy more healthcare.

And the state can’t stay out of things entirely. The Singaporean government still subsidises up to 80% of care in some cases, while MacCulloch acknowledges that the New Zealand state would need to keep providing unemployment benefits and healthcare for the very poorest. More generally, the global evidence is that competitive, user-pays systems for health and education are less successful than those that work collaboratively and are free at the point of use.

Then there’s Winston. He wants New Zealand to create a $100bn pool of infrastructure cash that would have parallels with Singapore’s Temasek, a sovereign wealth fund whose initial stake was created by commercialising state-owned enterprises. But if one wants a model for sovereign wealth funds, there are plenty in the democratic world, including that run by Norway (albeit using the proceeds from a past oil boom). And although, at a more general level, Singapore has remarkably good social outcomes, the countries that still outperform it are, predictably, the Scandinavians. And they do so while guaranteeing their citizens minor things like – you know – basic human rights.

More interesting than the flaws in this Singaporean love-in, though, is the reason the enthusiasm exists in the first place. There is a sense that, on one crucial point at least, New Zealand’s hands-off approach to the economy has failed. We are famously bad at saving, and that leaves us with relatively little to invest in things like infrastructure and start-up businesses. Even when we do have windfalls – like the Maui gas fields – we fritter them away. And so our economy languishes.

As Simplicity’s Sam Stubbs points out, Australia has five times our population but 38 times our retirement savings, thanks in part to a superannuation scheme that forces them to save 11% of wages. Stubbs, and others commentators, increasingly call for a two-birds-with-one-stone solution, in which we are somehow made to save more and thus generate domestic funds for investment.

In this context, Singapore, with its muscular approach to economic development, can look attractive. Compulsory savings accounts, meanwhile, evoke in part the traditional libertarian desire to individualise and marketise human life. But only in part. What’s truly fascinating is just how authoritarian these visions are. In a libertarian paradise, healthcare privatisation would leave people “free” to spend on medical treatment. The Singaporean version forces people to save large amounts of their salary to spend on certain things. It’s not that dissimilar to taxation, only with none of the efficiencies of Inland Revenue collection.

Partly this may reflect global trends: the American “new” right, for instance, which counts among its flag bearers people like JD Vance, is remarkably non-libertarian. It embraces tariffs on foreign goods, government-directed industrial policy, and even in some cases a particularly masculine version of trade unions.

Partly, also, Singapore’s popularity reflects a philosophical shift. At least in New Zealand, there is very little credibility left in the 1980s libertarian ideal that, if the state just got out of the way, everything would be fine. The average voter has clocked the poverty and dysfunction that that embedded. People haven’t forgotten the havoc that unregulated markets wreaked during the GFC, nor do they think that markets will solve climate change. They know that the countries with the smallest governments aren’t prosperous paradises but rather the failed states of Africa. The embrace of authoritarian Singapore, in short, symbolises the absolutely bankrupt state of modern libertarianism.