Vernon Tava’s Sustainable NZ Party launched over the weekend, to media fanfare. But has their pitch for centrist environmentalist voters lost touch with the changes in political reality?

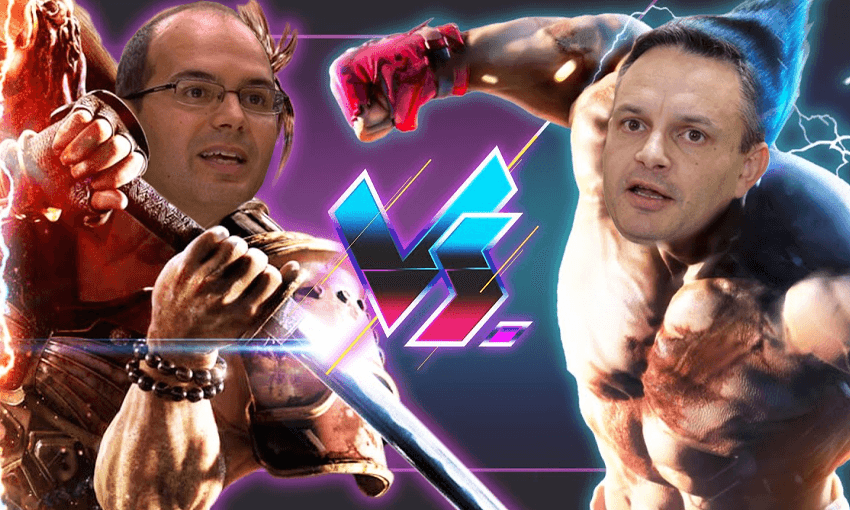

For a party that he criticises constantly, Vernon Tava will have a tough time escaping the shadow of the Greens.

It’s a curious position for the leader of Sustainable NZ – the party that launched over the weekend – to find himself in. People entering frontline politics generally need to have some sort of backstory that explains why they’ve decided to put themselves forward. The extent of Tava’s backstory that explains this current push appears to be failing to make headway in established parties.

Perhaps that is being too harsh. Tava has been a local board member, has had successes in both law and business, and is a widely used political commentator on commercial radio panel discussions especially.

But politically, his career has been defined by previous failed forays into national politics. When he ran for the Green co-leadership in 2015, 127 delegates cast a vote. One of them fell for Tava. When he went for the National nomination in the Northcote by-election not long after, he wasn’t among the five candidates who made the final shortlist.

The idea of “electability” is a common one in political coverage, particularly that coverage which is focused on who is up and who is down. On the evidence of those failed campaigns, it becomes extremely difficult to make the case that Tava personally is electable. If a benevolent major party were to attempt to stand aside in an electorate a la ACT in Epsom, would the voters play along?

The pitch of Sustainable NZ is a solid one. They would put environmentalism at the heart of any and all governments, by being willing to work with either major party, and being generally pro-business. There is almost certainly a constituency for it, and one that is almost certainly growing. People sometimes scoff at the idea of voters swinging between National and the Greens, but it is a real phenomenon. Sustainability NZ will argue that they can be the intermediary step in between.

It would have been a much more solid pitch as recently as the 2014 election, but now feels out of step with events. Among the current three-headed government, the Greens have been the party most willing to nuzzle up to National. They gave up an awful lot in other areas, in order to both get a few wins out of the other parties of government, and to get National’s agreement on climate change legislation.

By any objective measure, the Zero Carbon Bill has been the most consensus driven piece of legislation in this current term of parliament. The idea of “working with” a party being defined by simply putting them in government is an odd one, and not really reflective of how MMP now works.

Vernon Tava’s pitch is firmly rooted in the debates that swirled around the 2015 co-leadership race. But the problem for his new party is that his side of that debate did actually win that contest – it’s just that the candidate that benefitted was James Shaw.

Speaking to Kim Hill on Morning Report today, Tava suggested that huge swathes of the Green party membership are unhappy with Shaw, because he has compromised too much with other parties. There is some compelling evidence that this is true – witness for example the recent departure of prominent activist Jack McDonald, who went out the door taking swings at Shaw the Sellout. This isn’t a new phenomenon – most of the radical left has been contemptuous of the Greens for decades now.

But if that is the case, it takes a huge leap of cognitive dissonance to then land on the need for a brand new party. Because what Tava is basically saying with his point about the unhappy Green left is that in parliamentary terms, the new party he wants to put into government already exists.

Instead, he is left arguing against a phantom version of the Greens. That version is a party of Morris Dancing and micro-aggressions, of socialism and hurling the economy back to the Stone Age. Incidentally, it is the version of the Greens that primarily exists in right wing media, on radio stations like Newstalk ZB and websites like Kiwiblog.

Even the policies being pushed most heavily by Sustainable NZ are typically defined in relation to the Greens. A billion dollar boost is promised for conservation, much more than what the Greens managed to get out of Labour and NZ First. Sustainable NZ are also promising to move on genetic engineering, a sticking point for the Greens which some argue is an anti-science position in contradiction to their insistence on following scientific evidence on climate change.

Among their other policies, many are aimed at the architecture of government itself. There is a promise to create a minister for water, and a pledge to “ask councils to work with each other to improve efficiency.” Sustainable NZ would also establish a Parliamentary Commissioner for Animals, and change the tax system so that pollution could be taxed more, and income taxed less. They might be good ideas, but they’re hardly solutions that will light a fire under the electorate.

There is one party that will be put in a hugely difficult position by the emergence of Sustainable NZ. That is The Opportunities Party, who have also been positioning themselves in the “pro-environment but not the Greens” space. TOP still probably have the advantage over Sustainable NZ in having an existing party infrastructure, and their leader Geoff Simmons is arguably more prominent than Tava. But their already difficult task of scrapping their way to 5% in the party vote just got a lot more difficult.

For Sustainable NZ, they will need to make real headway in the polls, and quickly, to have any chance of catching on ahead of the 2020 election. The declining vote share for minor parties in recent elections shows voters are tactical, and if a party looks like falling under 5% they ruthlessly abandon ship.

Last time an explicitly centrist environmental party stood in a general election – the Progressive Green party in 1996 – they picked up only about 5000 votes. Since 1990, the Greens have never fallen below 100,000 party votes while running under their own banner. No party should ever consider itself to have a lock on any group of voters, but it is incredibly hard to imagine Tava putting a dent in his former party’s share.