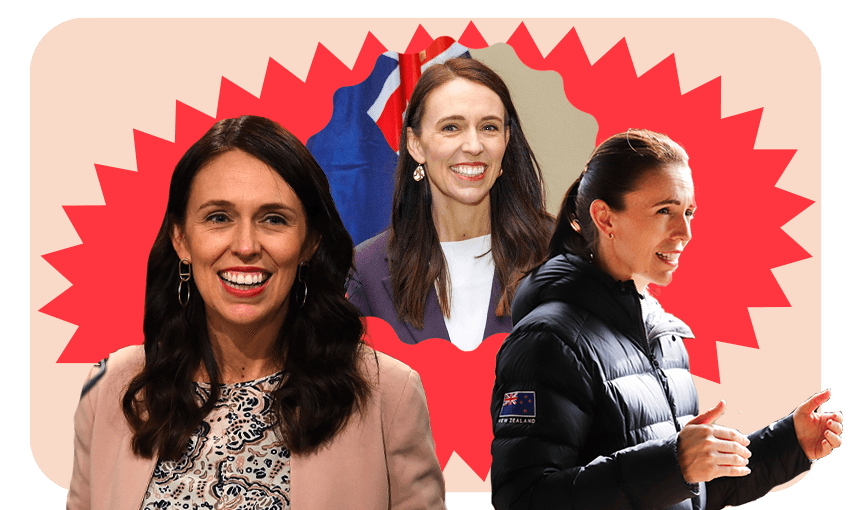

Sometimes the best person for the job is the one who doesn’t dream of it, writes her biographer Madeleine Chapman.

It is exceptionally rare for someone to rise to the highest position in their field without really wanting to. Most people try very hard and want it very much and get nowhere close to being the prime minister. Of the few that get there, most cling on until the bitter end when they have no choice but to fade out. Jacinda Ardern joined the Labour party in 2008, became deputy leader (reluctantly) in 2016, became leader (even more reluctantly) in 2017 and then the prime minister seven weeks later.

Which means her resignation on Thursday after nearly six years in office was somewhat predictable, though of course that’s easy to say after the fact. It wasn’t predictable for the reasons that many rumour-swirlers spouted (scandal, conspiracy etc), it was predictable because she never actually wanted to be the prime minister. Here is the opening paragraph to my 2019 book, Jacinda Ardern: A New Kind of Leader:

Jacinda Ardern did not want to be prime minister. “I’ve seen how hard it is to raise a family in that role,” she explained in 2014. A year later, she stated it more bluntly: “I don’t want to be prime minister.” Whether this was simply a party line or a more firmly held personal one, it sounded convincing.

I wrote those words in 2019, just a few months after Ardern became a household name around the world for her empathy and resolve in response to the Christchurch terror attack. She was extremely popular (hence the book) and was being held up as an example of a new kind of leader (hence the title). General commentary focused on her very short campaign, her baby while in office and her empathetic approach to leading. Nowhere in the global commentary was the consideration that actually she didn’t want to be doing any of this.

Even as late as June 2017, six weeks before becoming Labour leader, she told Next magazine her reasons for not wanting to lead the country. “It’s me knowing myself and knowing that actually, when you’re a bit of an anxious person and you constantly worry about things, there comes a point where certain jobs are just really bad for you.

“I hate letting people down. I hate feeling like I’m not doing the job as well as I should. I’ve got a pretty big weight of responsibility right now; I can’t imagine doing much more than that.”

In researching the book, I read nearly every single news article, blog post, tweet, facebook post and comment about and by her. I wanted to know whether these comments citing a lack of leadership ambition were genuine or simply a communication tactic to not overplay her hand as an opposition MP.

I spent months researching and writing that book and when I finished, I still didn’t know the answer. Was Ardern a fairly ordinary person – albeit an excellent communicator – who was in the game of politics with perhaps naive ambitions who somehow floated to the top? Or was she a brutal political operator who knew exactly how to get to the top while maintaining a warm and human reputation?

In the book, I concluded that she might just be a bit of both. No one becomes prime minister without wanting to, somewhere deep inside them. But of all the party leaders in recent years, I think Ardern wanted to be prime minister the least. She really did always want a family and, early on, appeared to see being a top politician as a barrier in the way of that ambition. Instead, she abruptly became prime minister and had a baby anyway.

So it’s no surprise, then, that the moments she will be most remembered for here and around the world are the moments that had little to do with regular politics. There was of course the baby. There was her composure under pressure and terror following the Christchurch attack. There was the same composure after the Whakaari eruption. And there was her world-leading early response to Covid-19, a masterstroke in national communication and a task few people in the world could do as well as she did.

Follow Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.

These were moments that required national unity and working together towards a shared vision. It was exactly what the naive MP of 2008 imagined politics could be. And when those moments became more like ordinary time and the day-to-day politics resumed, that’s when Ardern dipped. That’s when all the reasons she didn’t want to be prime minister came to the fore. The adversarial politics and the scrutiny and the tip-toeing and, in recent years, the vitriol and genuinely threatening behaviour towards the government.

All of those things are increased tenfold during an election, and in reality, Ardern has never had to campaign in a regular election. She had seven weeks in a “stardust” election in 2017, then a landslide victory in a pandemic year that required very little in the way of adversarial tactics. This year’s election would have been the first “classic” election in Ardern’s career as leader, and even a traditional politician would look at the year ahead with resignation.

Remembering what she said about raising a family while being prime minister, Neve starting school would have been no small factor in Ardern’s decision. Ultimately, that type of home life was all Ardern ever said she wanted, even as an MP. Unfortunately everyone else wanted, and then needed, her to do something else for a while.