Wellington mayor Tory Whanau spoke with Joel MacManus about how the new National government will affect the city’s transport plans.

Wellington mayor Tory Whanau isn’t ready to give up on light rail for the capital, despite the incoming National government vowing to scrap the project. She wants to take the new prime minister and transport minister on holiday to see some trams and hopefully change their minds.

“I’m still committed to light rail and I won’t rule it out,” she says. “I’ll be approaching the incoming government to sell the hell out of it,” she says.

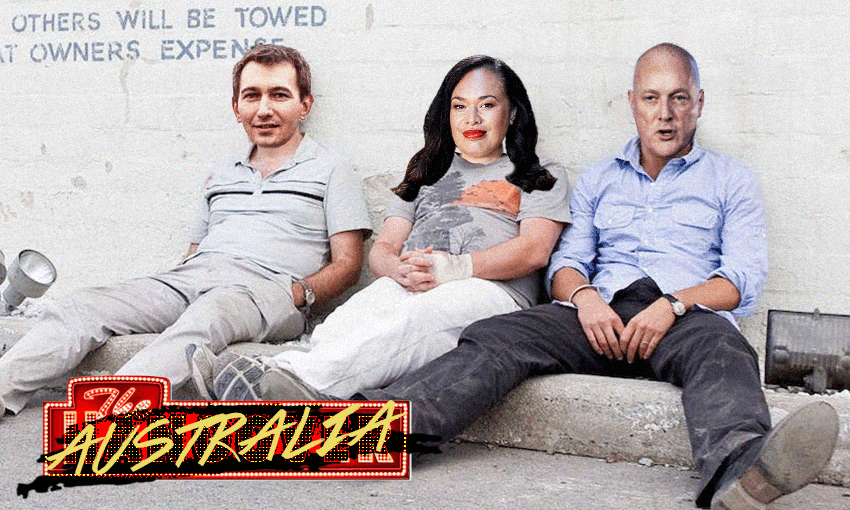

“What I’m proposing is that me, Christopher Luxon, Simeon Brown and our local MPs head over to Canberra, Brisbane or Sydney and look at their really successful projects. I am putting it on the table, saying ‘look, let’s go check it out and talk to the people who’ve experienced it.’ The second they’re sworn in, I’m going to put in a request, hopefully for early next year.”

The business case for mass rapid transit to Newtown and the southern suburbs is currently being finalised by staff from the combined council-and-government transport programme Let’s Get Wellington Moving. “We’ll take that to [Brown] and show him the economic benefits. I’m going to ask that we try to get it back on the table. It’s my role to speak on behalf of residents, who want this.”

The relationship between Whanau and probable incoming transport minister Simeon Brown is likely to be a rocky one. Earlier this year, Whanau said she was “deeply concerned” about the prospect of Brown as transport minister. “If he became transport minister I’d be really upset about that. It would see our climate change efforts going backwards,” she told Bernard Hickey on The Spinoff’s When The Facts Change podcast.

The two met before the election to try to patch some things over. “I met with him two months ago,” she says. “I told him: ‘Look, I’ve said things in the media, but if it’s likely you are the next government, I want to work collaboratively with you’. We acknowledged we had strong views and we were on opposing sides, but we committed to sit down and talk through some of these issues.

“I told him about how light rail will enable urban development with 20,000 new homes, and encourage more investment along the transport spine. He was listening. He didn’t agree to anything, but it was exactly the conversation we should be having.”

National’s transport manifesto for Wellington centred on cancelling the LGWM programme, though many of the component pieces will still go ahead, including grade separation at the Basin Reserve and a second Mount Victoria tunnel (though National wants four lanes of vehicle traffic while Labour wanted bus and bike priority).

The long-awaited Golden Mile upgrade is set to begin major construction early next year, and some minor works have already begun. The $139 million project was voted through by WCC and GWRC and will receive 51% funding from Waka Kotahi. It has been largely popular among public submitters, but has attracted strong backlash in some circles for its plans to restrict car access.

When it emerged that the major construction contract was still unsigned, Brown said he would look to scrap the project if elected. Whanau said the signing was “literally days away”, and will be completed well before the new government is sworn in. “He won’t be able to cancel it. it’ll be well signed by the time they’re sworn in, as it should be… The Golden Mile has been voted through, it has followed the democratic process, and it would be irresponsible to unwind that now.”

“Change is really hard, especially for those on the right,” Whanau said. “The conservative view of the Golden Mile is that it is a waste of money and not good for retail. They don’t see pedestrianisation and reduced cars as a good idea because they want to keep cities relying on cars. But Wellington has voted and agrees that’s not the way forward for our city.”

Before being elected mayor, Whanau was the Green Party chief of staff. Although she officially ran as an independent, she wears her political stripes openly. She’s naturally thrilled at the Green Party’s results on Saturday, especially in Wellington, where Julie Anne Genter and Tamatha Paul won the Rongotai and Wellington Central electorates.

Both candidates were at Whanau’s house on election day before heading to a results party at Eva Beva. “The screaming in the pub was phenomenal, it was one of the best moments I’ve experienced, it was so electric,” she said. “We knew it was not a great result for the left, but Wellington city has spoken and it has chosen. There’s a silver lining, and Wellington city and the Green movement can bring hope.”

Wellington’s Paneke Pōneke bike network plan is not expected to be affected by the new government. The 166km of bike lanes are funded mostly by council with some central government support through LGWM, but that funding has already been approved. “It would be incredibly difficult, if not impossible, for National to unwind that,” Whanau said.

Whanau said she was feeling optimistic about working with National on some city issues, especially new funding tools for local governments such as congestion charging, infrastructure financing and sharing GST revenue on rates.